By TREVOR HOGG

By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Apple Original Films and Warner Bros. Pictures.

While the term “reskinning” is associated with video games where the visual aesthetic is altered within the original framework, it is also an approach utilized extensively by filmmaker Joseph Kosinski, where live-action footage is digitally altered to take advantage of the innate reality while accommodating the needs of the story. This technique was critical in order to bring F1: The Movie to the big screen, as it allowed for broadcast footage to be intercut with principal photography to ensure that the racing scenes envisioned by Kosinski, and starring Brad Pitt and Damson Idris, were dynamic, executable and believable. An extremely high percentage of the 1,200 shots contributed by Framestore involved altering Formula One cars, which made reskinning much more significant than crowd replication and set extensions.

“The interesting thing about F1: The Movie is that it’s all got the motion blur of film. On the broadcast footage we added motion blur on top to give the sense of that 180-degrees shutter. In many ways, people are seeing F1 in a way that has not been seen since the 1990s, before F1 became this digital widescreen presentation format, and the blurry shutter went away. It feels quicker because of the way it blurs.”

—Robert Harrington, VFX Supervisor, Framestore

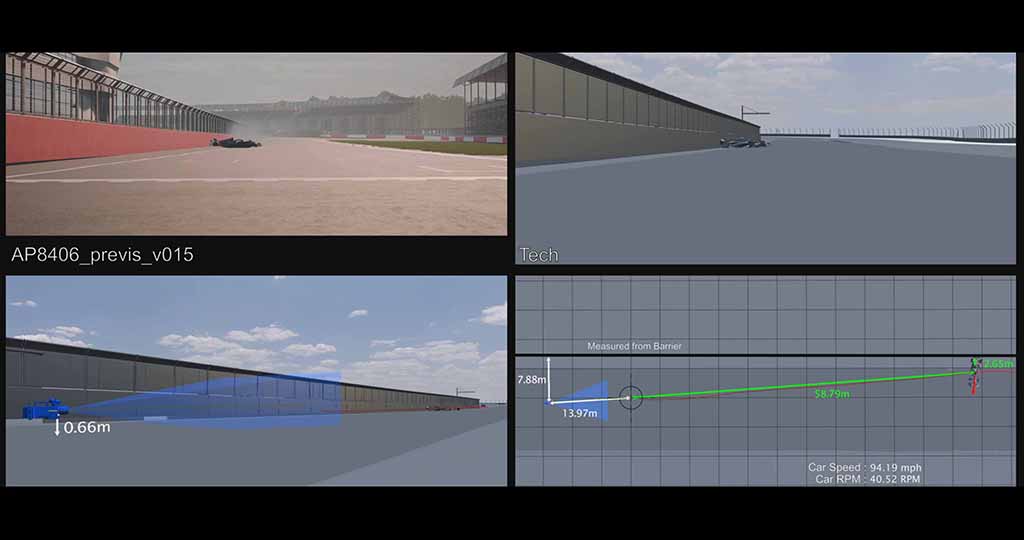

“It’s rare to have a shot where you were just adding crowd,’ notes Robert Harrington, VFX Supervisor at Framestore. “You would normally have cars and then there would be some crowd in the background.” Reskinning comes down to camera and object tracking. “For the Apex cars [driven by Brad Pitt and Damson Idris] we had CAD as a source. Whenever you see the broadcast shots, they get repurposed with a two prong-attack. Broadcast cameras are not like normal cameras. On the other side, you’ve got to have your objects to track in those shots. We would have a Williams car and turn it into an Apex car. To do that, we had to work out fairly accurately how big those cars were as well as their shapes to solve the camera tracking.”

Formula One’s massive archive of races was indispensable. “For the production shots, you know what those cameras are,” Harrington remarks. “You can go to the Panavision office and grid all of these lenses. Conversely, broadcast cameras have tiny sensors, and because they’re filming real events, the zooms are humongous. One of them had a Canon UJ86, which goes from 9mm to 800mm. These humongous zooms are quite hard for us to work with. If I took a camera setup with an 800mm zoom and a tiny sensor, but then put the lens on a Sony Venice camera, it would be the equivalent of around 3000mm. We have to work around that and still get the ability to put the cars in those broadcast shots. Beyond that, you have all of the motion blur and the shaking cars, so tracking was a point of focus.”

Terrestrial LiDAR scans were taken of the entire racetracks, and textures were captured by drones. “By perhaps Tuesday, everything would have been taken down from the race, so we had to add some props and sponsors back in,” Harrington notes. “You can’t only use the LiDAR. They would be filming in the week following the race and would go around a corner where, during the race, they might have had a bright yellow Pirelli sponsor on the lefthand side, but now there’s nothing there, so there’s nothing to reflect onto the car they’re filming with the actor. We had a nice car asset. We spent time on the micro scratches and all the little details so that we could render a car that looked like the car on the plate. We could replace panels and areas.”

“We found some references of hot laps for specific racetracks, for example, Carlos Sainz’s best lap in Monza, to have what speed at what corner. We tried to be accurate to that. … The shots used the original filmed cars with stickers on them, for example, a Ferrari sticker on an AlphaTauri car, to indicate which car should be replaced in each shot. We were able to use the actual speed of the footage as a reference. We paid close attention to vibration on the car, and how the camera was shaking to give a sensation of having a powerful engine behind you.”

—Nicolas Chevallier, VFX Supervisor, Framestore

Creative license was required for the digital cars. “We tried to do the best we could to model the car as closely as possible,” states Nicolas Chevallier, VFX Supervisor at Framestore. “But it’s not something where you can go to the Red Bull team and say, ‘May I take pictures of your car in every detail?’ It’s like a secret.” Lighting was tricky throughout the movie. “Monza and Silverstone are sunny; however, the last race in Abu Dhabi starts in daylight and then goes all the way up until night. The lights around the racetrack in Abu Dhabi were important to match. Yas Marina racetrack has a complex setup of lights, probably engineered for every single one; recreating this was a challenge, mostly at night. We had real-life reference underneath, so we tried to get as close as possible to the car that we were replacing. A strategy was developed for the tires. Chevallier notes, “We had a massive database to say, ‘Ferrari needs to have the #55 and has to be on red tires.’ We had to build a comprehensive shader to be able to handle a lot of settings to change the number on the car, the yellow T-bar or to alter the tire color to make sure they had the right livery for every single track. For example, Mclaren has a different livery for Silverstone. Actually, you’re not building 10, but 20 cars in various states. We had different variations of dirt and tire wear.”

Shots were tracked through Flow Production Tracking. “We developed some bits in Shotgun so we could control car numbers, tire colors and liveries,” Harrington states. “It was driven entirely at render time essentially with Flow Production Tracking to find out how each car should be set up for liveries, helmets and tire compounds; that gave us a level of flexibility, which was good because there are lots of shots.” The Formula One cars needed to look and feel like they were going at a high speed. “We found some references of hot laps for specific racetracks, for example, Carlos Sainz’s best lap in Monza, to have what speed at what corner,” Chevallier explains, “We tried to be accurate to that. The editorial team provided us with a rough cut of a sequence. The shots used the original filmed cars with stickers on them, for example, a Ferrari sticker on an AlphaTauri car, to indicate which car should be replaced in each shot. We were able to use the actual speed of the footage as a reference. We paid close attention to vibration on the car, and how the camera was shaking to give a sensation of having a powerful engine behind you.”

“Whenever you see the broadcast shots, they get repurposed with a two prong-attack. Broadcast cameras are not like normal cameras. On the other side, you’ve got to have your objects to track in those shots. We would have a Williams car and turn it into an Apex car. To do that, we had to work out fairly accurately how big those cars were as well as their shapes to solve the camera tracking.”

—Robert Harrington, VFX Supervisor, Framestore

Motion blur had to be added. “We have the footage they shot with the same production cameras, such as the Sony Venice, which was 24 frames per second and 180-degrees shutter, so it had the motion blur look of film,” Harrington notes. “Broadcast footage always uses a very skinny shutter, which minimizes motion blur. This is done so viewers can clearly see the action, whether it’s in sports like football, tennis or auto racing. Whenever you press pause, everything is fairly sharp. Things don’t look ‘smooth,’ and it affects how you perceive the speed of the shot. The interesting thing about F1: The Movie is that it’s all got the motion blur of film. On the broadcast footage we added motion blur on top to give the sense of that 180-degrees shutter. In many ways, people are seeing F1 in a way that has not been seen since the 1990s, before F1 became this digital widescreen presentation format, and the blurry shutter went away. It feels quicker because of the way it blurs.”

Reflections on the racing visors were not a major issue. “I have done my fair share of visors in my career,” Harrington notes. “But it wasn’t a problem on this one. The visors were in all the time because they’re really driving cars.” Sparks are plentiful on the racetrack. “Most of the time we tried to keep it like the sparks that were actually on the footage. We did some digital sparks for continuity, but always had the next shot in the edit to match to.” Chevallier states. Broadcast footage uses a different frame rate. Harrington observes, “The only battle would come when you had particularly sharp sparks in a broadcast shot and had to re-time it from 50 frames-per-second skinny shutter to 24.”

Rain was a significant atmospheric. “Monza was shot without rain because it was not raining in 2023, so the Monza rain was a mix of the 2017 race,” Chevallier reveals. “It was funny how old-fashion the cars looked, so they had to be reskinned for the rain. We also had to add rain, replace the road, insert droplets, mist and rooster tails. There was lots of rain interaction. The challenge was to create all the different ingredients combined at the right level to make a believable shot while keeping efficiency regarding simulation time. We had little droplets on the car body traveling with the speed and reacting to the direction of the car. Spray was coming off the wheels, sometimes from one car onto another one. We had to adjust the levels a couple of times. Lewis Hamilton had some notes as a professional driver, and told us to reduce the rain level by at least 50% or 60% as it was too heavy to race this amount on slick.”

“For the production shots, you know what those cameras are. You can go to the Panavision office and grid all of these lenses. Conversely, broadcast cameras have tiny sensors, and because they’re filming real events, the zooms are humongous. … We have to work around that and still get the ability to put the cars in those broadcast shots. Beyond that, you have all of the motion blur and the shaking cars, so tracking was a point of focus.”

—Robert Harrington, VFX Supervisor, Framestore

Production VFX Supervisor Ryan Tudhope organized an array camera car that people saw driving around the races. “Panavision went off and built it,” Harrington states. “It had seven RED Komodos filming backplates plus a RED Monstro filming upwards with a fisheye lens. Komodos are global shutter cameras, so they don’t have any rolling-shutter skewing of things that move past. The camera array positions were calibrated with the onboard cameras. This allowed us to always capture the shot of the driver from the same consistent position, even in scenes with rain. We made sure that the array was designed to maximize coverage for these known angles on the car, and that’s what Framestore used to then replace the background. They never had to do virtual production.”

All of the racetracks are real. “We’re not doing CG aerial establishing shots,” Harrington remarks. “We added props, grandstands and buildings to them.” The crowds were treated differently for each racetrack. “The standard partisans have a specific shirt, but they don’t have the same shirt in Monza or Silverstone,” Chevallier observes. “It was like a recipe with the amount of orange and red, and clusters of like fans all together, to make them seamless with the actual real F1 footage. We were looking at static shots of crowds with people scratching their head or putting their sunglasses on. It was like a social study,”

“Personally, I’ve watched F1 since I was a kid,” Harrington states. “What was interesting for me was that we got to forensically rebuild events from the sport’s history. We actually found out how high that guy’s car went, or how fast an F1 car actually accelerated.” The visual effects work placed everyone in the driver’s seat. “The thing that impressed me is when we did a few shots and had to matchmove all of the helmets and hands,” Chevallier recalls. “I gave notes to the team saying, ‘Okay, guys, there are some missing frames because it looks like it’s shaking like crazy.’ I had a look frame by frame, and the heads of the guys are jumping from the left side of the cockpit to the right side in less than a frame. I was surprised by all of the forces that apply to this. Some things you would give notes because it looks like a mistake we kept because that was what it was really like for the driver. I’m still impressed by all of this.”