By CHRIS McGOWAN

By CHRIS McGOWAN

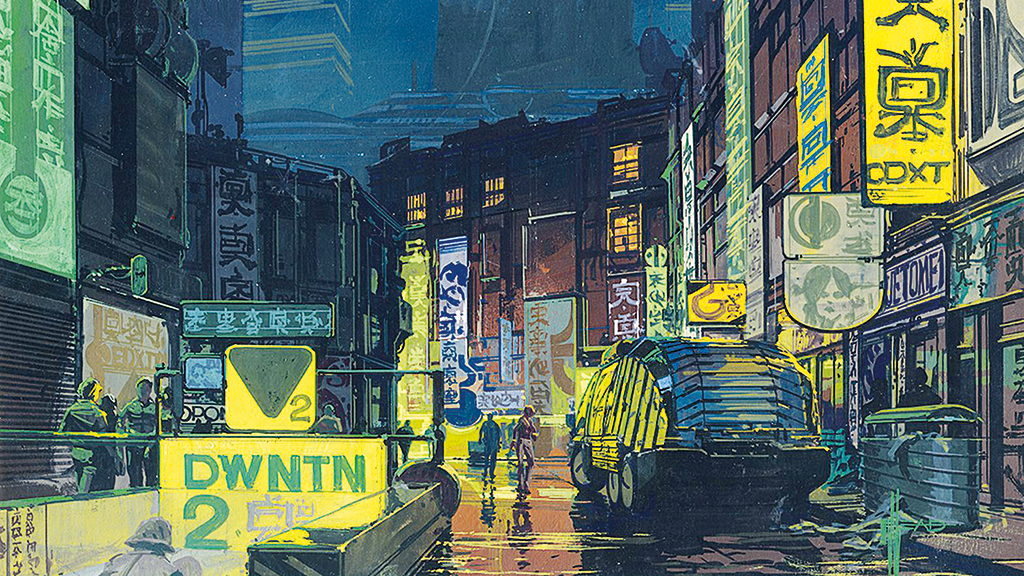

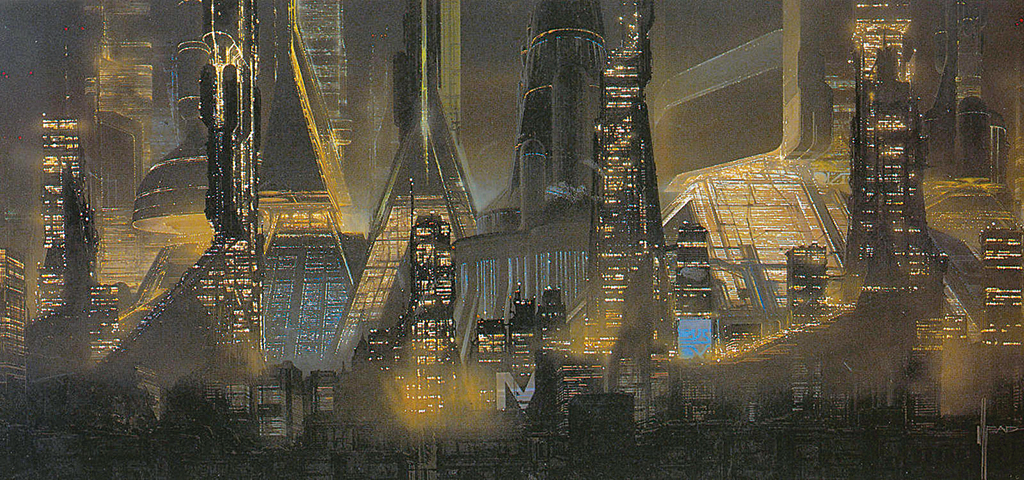

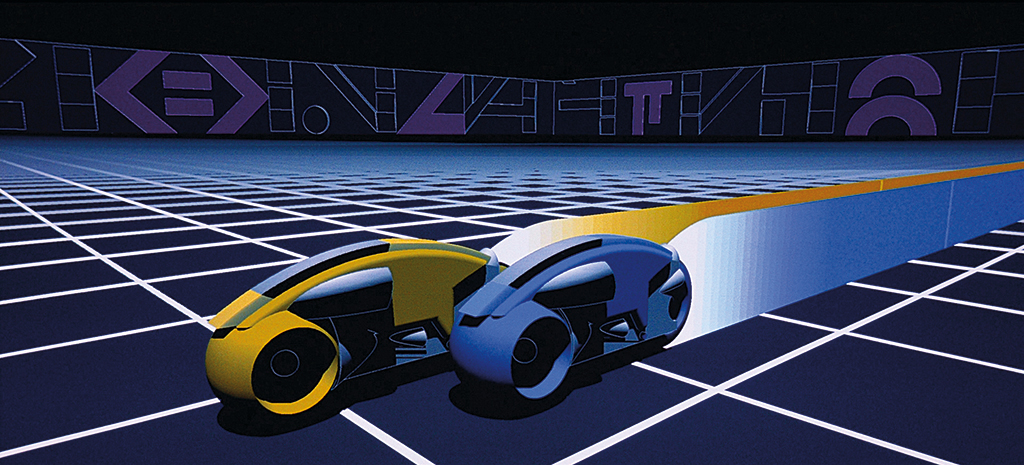

The future many of us imagine has been greatly shaped by the gouache paintings of Syd Mead, who provided conceptual art for Blade Runner, Tron and other science fiction films.

Blade Runner has become a cinematic template for a gritty hightech future with dystopian and/or noir edges, while Tron was the first visual representation of cyberspace, before the term entered popular culture. Mead also stimulated our minds with spaceship designs for Aliens and 2010, and a conception of the V’ger entity for Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

He designed vehicles, costumes, gear and cityscapes for Timecop, Short Circuit, Strange Days, Johnny Mnemonic, Mission to Mars, Tomorrowland and Elysium. His influential designs and illustrations have been published in books like Oblagon and viewed widely on the Internet. Mead received a VES Visionary Award from the Visual Effects Society in 2016, and his work has been highlighted in two recent books: The Movie Art of Syd Mead: Visual Futurist (Titan Books, 2017) and A Future Remembered: An Autobiography (2018, available at sydmead.com).

Sydney Jay Mead was born in 1933 in St. Paul, Minnesota, but moved within a few years to Colorado Springs. His father was a fundamentalist Baptist minister who set aside the Bible to fuel a young Syd’s imagination with tales of Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon. Following high school, Mead served for three years in the Army in Okinawa, and then enrolled in ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California, where he now resides.

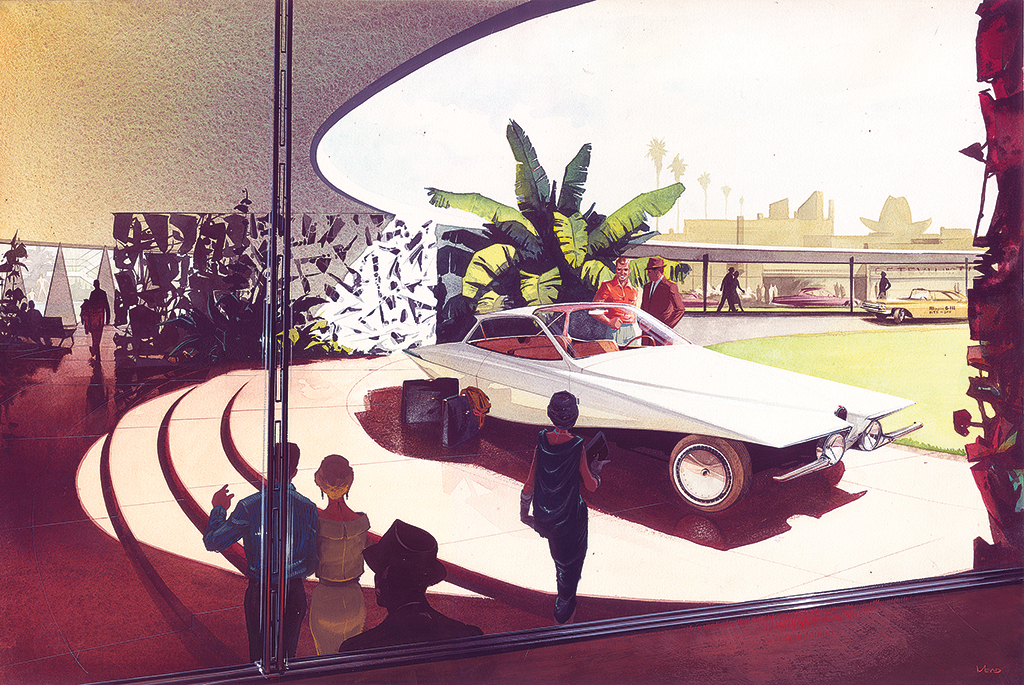

“I studied Industrial Design, with a major in Automotive and a [minor] in Product. It gave me a knowledge of how things hinged together and how molds are made and things like that,” says Mead. His time at ArtCenter helped him create functional-seeming art – the vehicles he designed were strikingly beautiful and also seemed like they would work – in the near or distant future.

“If you have the industrial design methodology in your mind, things look the way they do because of how they’re made. And if you’re working on a movie or some other story format you first have to ask, ‘What is the socioeconomic, the technological world in which this story is taking place?’”

After graduating, Mead spent two years with Ford and then went out on his own with catalog design, architectural renderings for major firms, 747-jet interiors, show cars, luxury ships and assorted product design. Philips Electronics, U.S. Steel, Sony, Minolta and Honda were among his corporate clients. He moved to Southern California in 1975. He had been making quite a good living for almost 20 years before Hollywood knocked on his door.

“I got a call from John Dykstra and his partner Bob Shepherd and they said, ‘Would you like to work on a science fiction movie?’ I have no idea how they knew I was out here. Not a clue. So I said, ‘Sure’ and I met them at their Van Nuys studio, Apogee. I worked on Star Trek: The Motion Picture with Robert Wise in post.”

Mead designed the V’ger entity that was central to the plot. He sketched the final end view of the V’ger on a cocktail napkin in a hotel in Eindhoven, Holland, where Mead was visiting Philips. “I was having a triple martini. I guess it was inspiration of a sort,” he laughs. That first Star Trek movie debuted in 1979 and breathed new life into the franchise.

Soon afterwards, Ridley Scott was in Los Angeles putting together an unusual new movie, Blade Runner, based on a story by Philip K. Dick. Scott had seen Mead’s futuristic work in a book published by U.S. Steel and was intrigued by “one picture which has this night shot, a rainy, evil night, and these cars all driving on this huge expressway into the city and just this vertical wall of architecture,” recalls Mead.

“I studied Industrial Design, with a major in Automotive and a [minor] in Product. It gave me a knowledge of how things hinged together and how molds are made and things like that.”

—Syd Mead

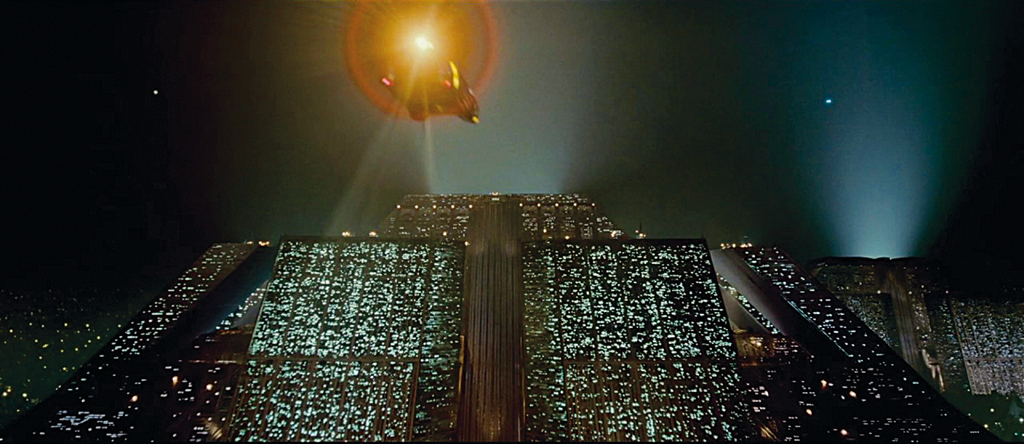

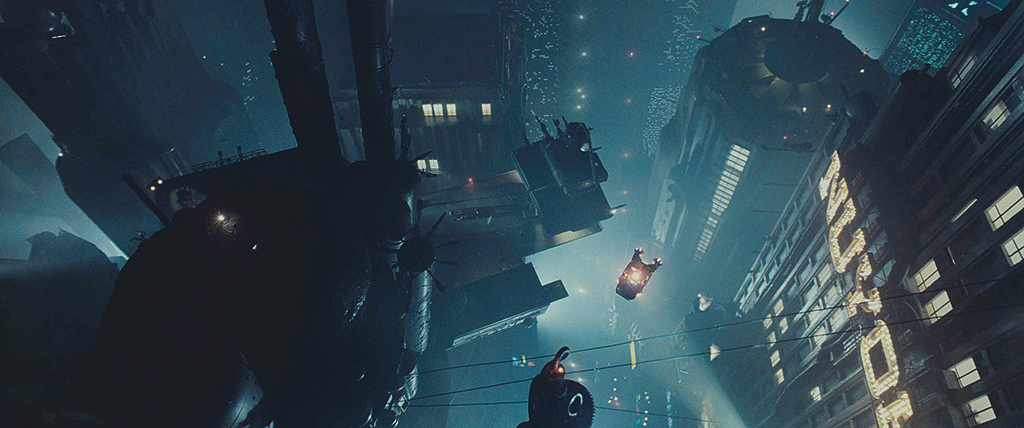

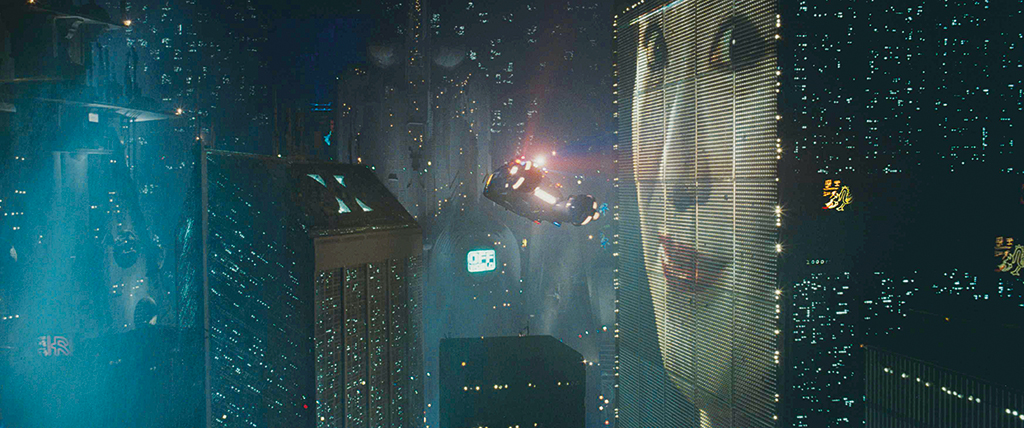

“Ridley called and I met him at the Playboy building on Sunset. And Ridley said, ‘This is not going to be Logan’s Run [a rather conventional sci-fi film].’ And I was the first person on the official roster as a hire for the film. Ridley wanted the streets to look packed and he wanted the visual frames to be packed. And I thought, ‘If we want to pack the streets, why don’t we just move the façade out like they do in Europe and have the columns and have an arcade underneath, because that narrows the street, and have garish lighting and the Japanese kanji.’ I had all the signage in fake kanji and later had a consultant to actually make it mean something. I did the gouache paintings [while] Ridley was busy fighting with the finance people.”

In terms of the buildings and cityscapes, Mead sought to “mash together Mayan and Byzantine and Moderne and Memphis [an Italian geometric, post-modern style] and anything I could get my hands on because it’s a jumbled up world, a dystopian world. And we just jammed it all together.” It was a look that was layered – with the new atop the old – and Mead sometimes jokingly referred to it as “retro deco” or “trash chic.”

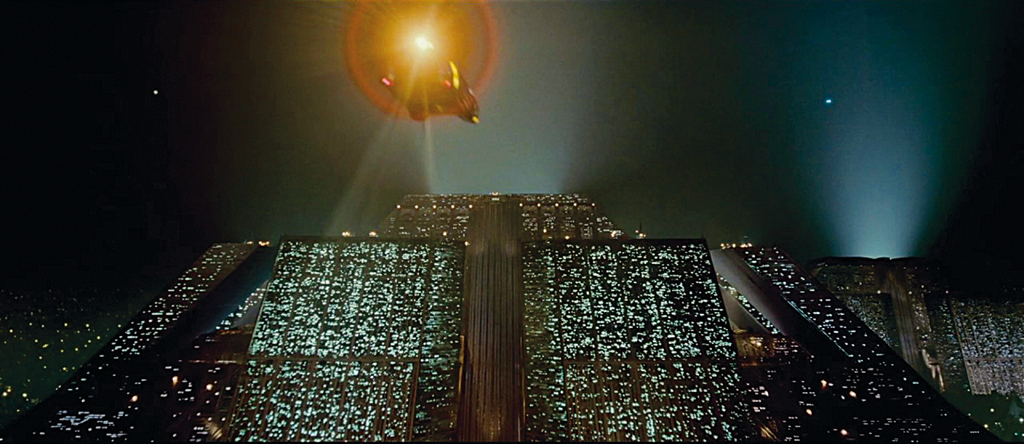

Mead designed the iconic “spinner” flying cars and a cityscape with towering buildings. “I thought, ‘If this building is 3,000 feet high, we’re going to need a larger access footprint.’ So I had these pyramids coming out maybe in a four-block plot.” The rich lived near the top and “the nice people didn’t go below the 40th floor, so the street became the basement of society.” It was a future Los Angeles that was “high-tech and full of low-life,” as has been said about much science fiction that followed in its path. It was densely populated and harshly polluted, neonbright, and grimy where the ordinary folk lived. The film’s look and attitude influenced a generation of science fiction writers and filmmakers. Blade Runner bowed in 1982 and “changed the way the world looks and how we look at the world,” the renowned sci-fi author William Gibson told Wired. Mead recalls, “Philip K. Dick [who passed away in 1982] was very happy with the first rough cut, very pleased.” The film’s credits listed Mead as a “visual futurist.”

As Mead started work on Blade Runner, “I got a call from [producer] Donald Kushner who says, ‘I’m working on a movie over at Disney called Tron and the director is Steven Lisberger.’ I had lunch with them, and when I finished pre-production on Blade Runner I went into pre-production on Tron. You can’t imagine two more different movies.” Tron was the first feature film to make extensive use of computer animation, as well as the first to explore cyberspace (before Gibson popularized the term). Mead designed light cycles, tanks and aircraft carriers for the electronic world.

About the film’s setting, he remembers, “It dawned on me that everything’s taking place on the back side of a CRT tube. So there’s no gravity. The rules of the real world don’t apply anymore. So I was in a meeting with Lisberger and he said, ‘We’ve got these light cycles and how are we going to make them turn? Because it’s going to take a lot of animation to make that curve.’ And I said, ‘No, there’s no gravity, there’s no inertia, so just make them do a 90-degree turn – bang like that.’”

Mead’s back-and-forth between the two films continued. Once Tron went into principal photography, Mead went “back to post-production on Blade Runner,” doing matte shots with Effects Supervisors David Dryer and Douglas Trumbull, VES, and then returning to Tron after that. “That was a movie made under extreme duress. A lot of the Disney animators at that time would not work on the film because Disney was using computers. How that’s changed!”

“I’m very fortunate because I go in at the zero point. They want an idea to go along with the script, to illustrate the script, and so I work on a movie about every two years, by referral mostly, by the director or the production design people. I go in to the project as if I’ve never worked on a movie before, ever, so I don’t have any preconceptions.”

—Syd Mead

His next major film project was Peter Hyams’ 2010 (a sequel to 2001: A Space Odyssey), for which he had to design the Leonov spaceship that travels to Jupiter. Not long after, Mead was traveling and got a call from his office. “They said, ‘James Cameron is sending a script down to you.’ It arrived FedEx and I read the script for Aliens. And on the way back on the plane I started drawing the Sulaco [the film’s spaceship], and the script said this large forest of antennae comes into frame from the lower left, and this huge bulk of machinery follows it. And [I thought] let’s do a sphere because that’s a sort of universal shape, with these antennae coming out in front of it. So I get back here and have three sketches done and have a meeting with Cameron at his house that was then on Mulholland Drive. He said, ‘Well, Syd, we’ll make a model of this, and it has to move past in front of the camera and I don’t want to pull focus to keep the globe in focus. It has to be flatter.’ So he drew me a little quick sketch. Then I did the Sulaco sort of as an armed cargo ship. And I did some interior sets – the dropship bay and I started on the loader, also.”

“I’m very fortunate because I go in at the zero point,” continues Mead. “They want an idea to go along with the script, to illustrate the script, and so I work on a movie about every two years, by referral mostly, by the director or the production design people. I go in to the project as if I’ve never worked on a movie before, ever, so I don’t have any preconceptions.”

Mead also worked on the Japanese anime titles Yamato 2520 and Turn A Gundam, and, along the way, the video games CyberRace, Cyber Speedway, Wing Commander: Prophecy and Aliens: Colonial Marines. He was also involved in some notable projects that never got made – such as The Jetsons – and two billion-dollar theme parks in Japan.

Mead’s most recent film work was for Blade Runner 2049. “Denis [Villeneuve] came over here [to Pasadena] a couple of times to explain what he was after. So I started doing the Las Vegas street scenes, the skyline and different things. The script was very secret. I had to get a secure download to read just the Las Vegas part. But it was exciting. He’s a wonderful man to work with and he wrote the foreword for the book, The Movie Art of Syd Mead.”

Mead advises young people working on visual effects or design to “notice everything. Sophistication is basically having a very good memory, whether it’s language or music or painting. You have to eventually build up your internal library of things you remember and how they should look. You can’t adjust something if you don’t know how it looks in the first place. Just remember how things look, because the tools are changing all the time, so you’ll relearn that. You have to feed in from your personal memory banks, and if your banks are better than somebody else’s you’ll probably get the job.”

Regarding the success of Blade Runner, Mead comments, “You don’t know it’s going to become a classic. You make a movie and the public decides if it likes it, and that’s how classics are made. So I was very fortunate.”

Read more about the miniature effects in the original Blade Runner here

Read more about the miniature effects in the original Blade Runner here