By IAN FAILES

By IAN FAILES

“The script was pushing us to do things that we maybe hadn’t done before. But, on the other hand, we had Dennis Muren, VES at the helm, and Dennis is just the best when it comes to figuring out how to do effects.”

—Dave Carson, ILM’s Visual Effects Art Director on Willow

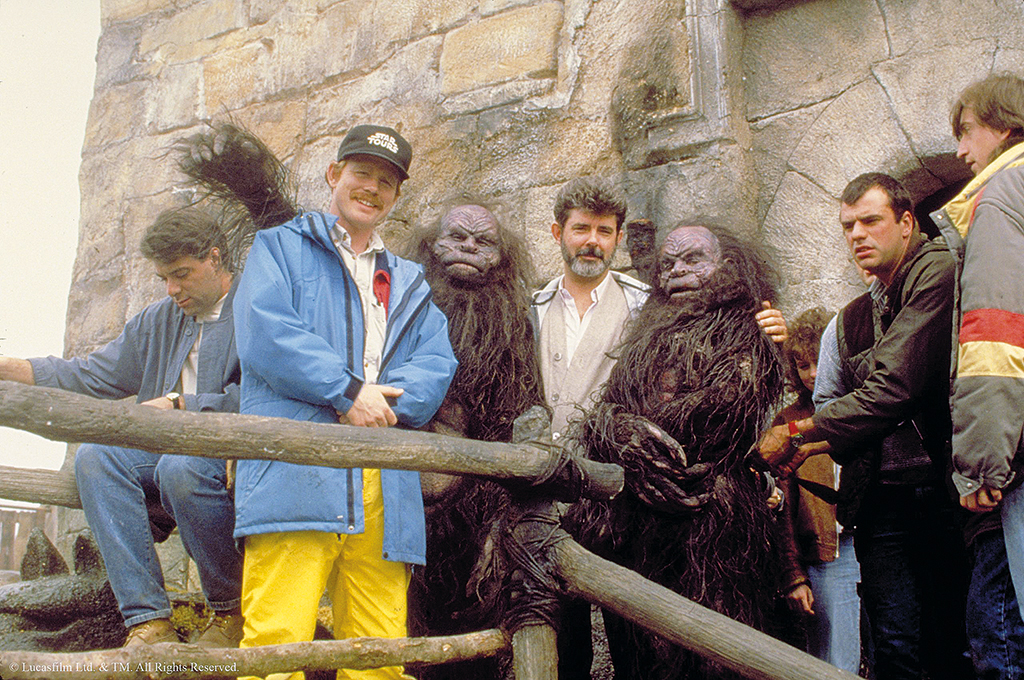

Thirty years ago this May, director Ron Howard and producer George Lucas combined to bring Willow to the big screen. The story of a dwarf who finds himself protecting a baby from an evil queen provided a classic showcase of the visual effects might of Industrial Light & Magic (ILM). Featured in the 1988 film were numerous animatronic characters, matte paintings, miniatures, miniaturization effects via oversize sets and bluescreen compositing, stop-motion animation and even rear projection.

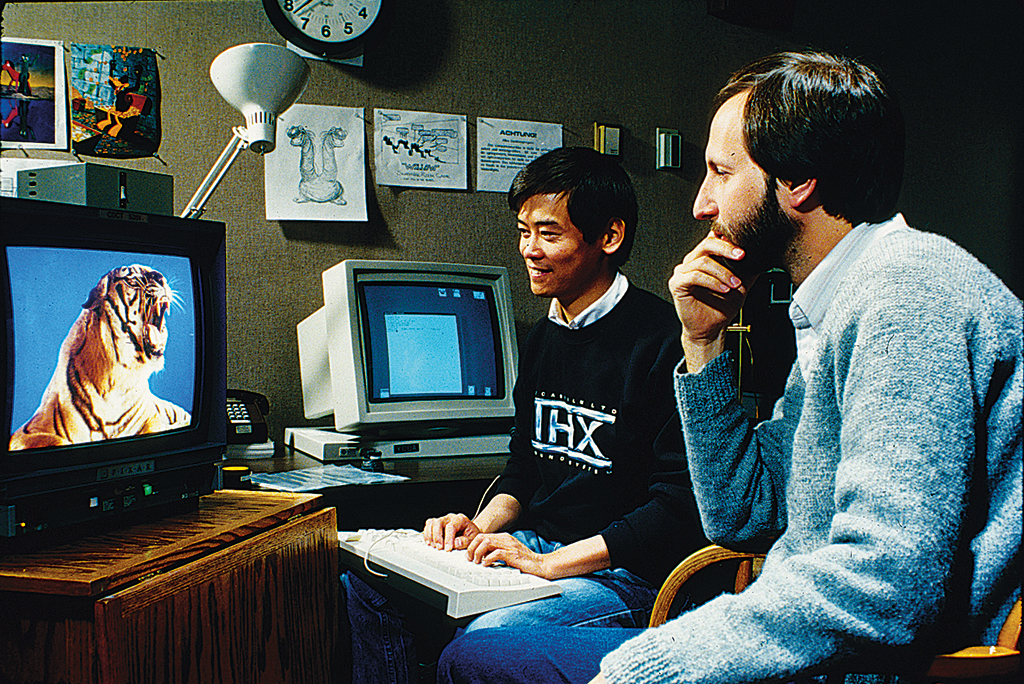

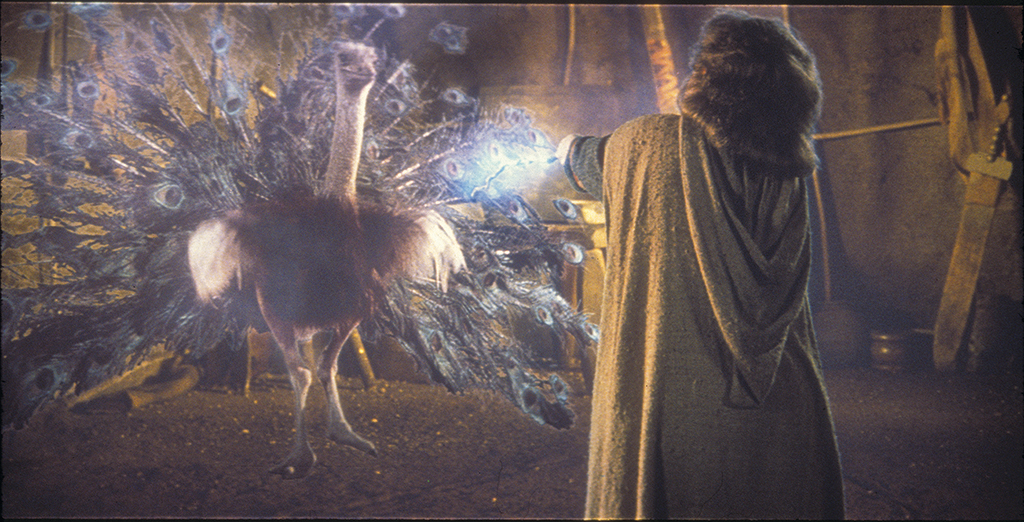

But the VFX-Oscar nominated Willow, which was supervised by Dennis Muren, VES and Michael J. McAlister, also represented a shift towards the digital realm of visual effects. This was thanks largely to ILM’s innovative 2D transformation system called MORF, used for a critical magical scene in the film that transformed a series of animals – from one to the other – and finally into an old sorceress, all in single, unbroken shots, which would ultimately lead to many more morphing effects in subsequent films.

The film’s fantastical imagery involved a significant design effort, much of it still done traditionally with pen and paper. On its 30th anniversary, VFX Voice spoke to ILM’s Visual Effects Art Director on Willow, Dave Carson – a veteran of The Empire Strikes Back, Return of the Jedi, Titanic and later Casper, Forrest Gump and Jurassic Park – about his perspective on those design stages, the shift to digital, and the mammoth effects effort put into the film.

VFX Voice: What are your memories of coming onto the film, initially?

Dave Carson: At that time, I was head of the art department at ILM. My earliest recollection is sitting in the art department meetings with George and Ron, as they talked about the early drafts of the script, to give us an idea of the kind of imagery they would like to see us do.

The script was still pretty fluid. They had a strong outline, but they were still open to changes as we contributed art and as they continued to have their story meetings. George had also brought in Moebius [pen name of French artist Jean Giraud] to do some concept art based on this early outline. I remember those pieces showing up, and they were really fun to look at. He would do these beautiful ink drawings and then he would Xerox them and color the Xeroxes. He never colored the originals.

I had also just brought in a couple of new artists. One of them was a storyboard artist, Dave Lowery. There was another young man, Richard Vander Wende, who came on as a concept artist. He did these beautiful Ralph McQuarrie-esque kind of paintings.

VFX Voice: What was involved in your role as visual effects art director?

Carson: Apart from the initial design work, I would go to dailies every day and Dennis would sometimes ask my opinion on how things looked, how shots looked. For some reason, early on, he decided that I should be the expert on whether the blue glow of the wand in the film was consistent from shot to shot. I don’t know how I got saddled with that chore, but that was one of the things that I was always asked about almost every daily: if the degree of blue glow on the wand was appropriate from shot to shot.

VFX Voice: One of the things about Willow is that the visual effects were largely still done in the practical and optical days, but then it also saw the advent of morphing. What was the feeling there at ILM about how the effects techniques would be combined?

Carson: George definitely was pushing us to do the most that we were capable of, using the technology at the time. Phil Tippett [VES] was still using traditional stop motion for the Eborsisk monster, and optical was being pushed to its limits. And the morphing thing was a huge challenge as well. The script was pushing us to do things that we maybe hadn’t done before. But, on the other hand, we had Dennis Muren [VES] at the helm, and Dennis is just the best when it comes to figuring out how to do effects.

VFX Voice: What do you remember about how the morphing shots came about?

Carson: I remember we had a meeting early on. It was myself, Dennis and George H. Joblove and Doug S. Kay, who were from the brand new computer graphics department. They were concerned about how they were going to do the scenes where the animals change from one to another. They had assumed that what they would do is build a computer model of each of the animals and then have those models, or the polygons that made up those models, shift from one animal to the next, which was a kind of a known technology.

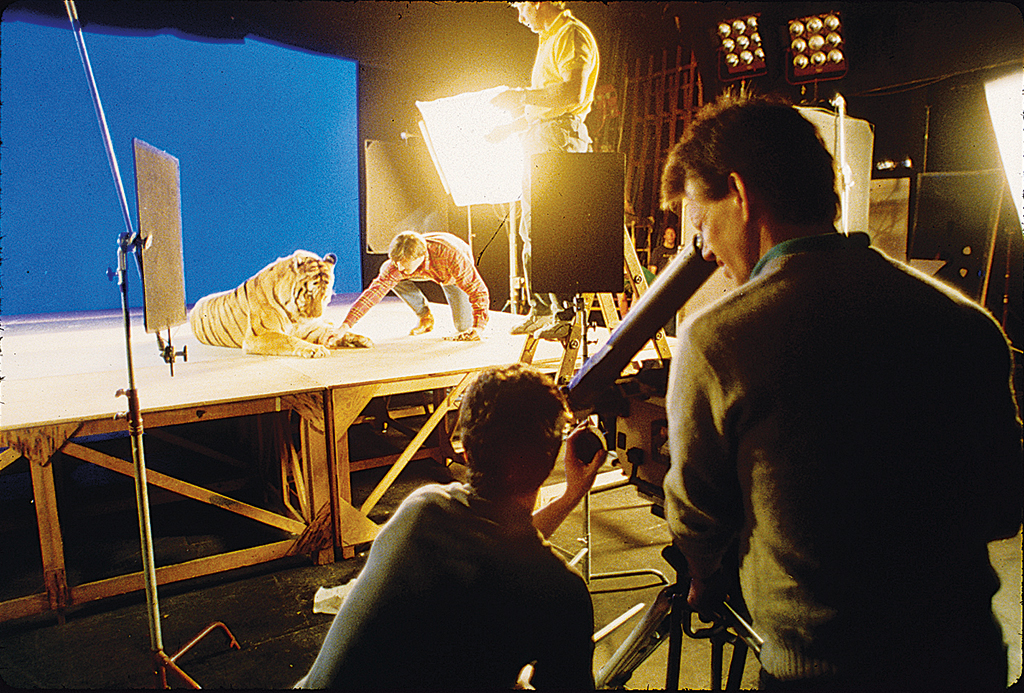

But what concerned them was that they weren’t sure they could make computer models of animals that looked sufficiently real. They couldn’t do hair at the time, either. The challenge wasn’t getting them to change from one to another, the challenge was getting them to look real enough.

We were kicking things around and I said, “Well, instead of doing it as a model, what if you just did it as images?” I thought this would work because the computer knows where all the pixels are. They know the pixels that are making up each image. So the idea was, what if you changed from one image to the next, rather than the computer graphic representation of the animals?

Doug and George were intrigued by that concept and they said, “Yeah, maybe that would work.” And they went back and they enlisted the help of Doug Smythe, who was in the computer graphics department. I believe they found somebody who had written a SIGGRAPH paper that had suggested kind of a similar possible approach. They came back with this program that was our MORF system, which basically takes a grid and lays it over imagery and then just shifts the pixels around, so that all of the transformation really happens in a 2D space with no computer models. That was a big breakthrough, technologically.

VFX Voice: In the film there are some sorcery and lightning scenes that utilized a lot of effects animation. How was that achieved back then?

Carson: That was all hand-animated with articulated mattes on cells. I remember doing some paintings to work out the look. I took a cell background and showed the animation team how some effect might look. Wes Takahashi supervised that work. The guys in the animation department had become pretty proficient at doing all this effects stuff. Of course, now it’s all done with particle systems, but at the time it was very tedious work.

VFX Voice: There’s some fun miniaturization effects for the small Brownies characters. How was that done?

Carson: The biggest challenge was that the Brownies had to walk. So they had to work out how those Brownies, being their height, keep up with people who are much taller, and what their walking speed was. It was all shot bluescreen. It was a lot of work. I just remember them shooting day after day on the main stage at ILM. Mike McAlister worked out most of the scale and the scale-size props and the pieces that he would need for bluescreen.

VFX Voice: Are there any specific things you’d like to share about the visual effects production process on the film?

Carson: I remember the gradual simplification of the film. The original script was more challenging. For instance, there was a scene where everybody was on their way to the castle, or wherever they were going. They found a door in a mountain, and they went through this series of caves and had some escapades, and eventually encountered this dragon and had a big fight. It was a great sequence, but as time went by they lost the cave, they moved the dragon to the moat of the castle. It was all simplified to a point that it lost a lot of its drama.

“The dragon, Eborsisk, was named after [well-known TV/film critics] Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel; Ron [Howard] wanted to know if it could have two heads, and Phil [Tippett] said, ‘Yeah. Why not?’”

—Dave Carson, ILM’s Visual Effects Art Director on Willow

I know Phil Tippett, VES was frustrated that his dragon, in the end, had to live in just a little moat. And the dragon had two heads because, well, I remember Ron saying, “Would it be weird if the dragon had two heads?” And the reason, of course, was that they had decided to name the bad guys after film critics. General Kael was the main bad guy and was named after Pauline Kael, a critic for The New Yorker. And the dragon, Eborsisk, was named after Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel [well- known TV/film critics]. Anyway, Ron wanted to know if it could have two heads, and Phil said, ‘Yeah. Why not?’”

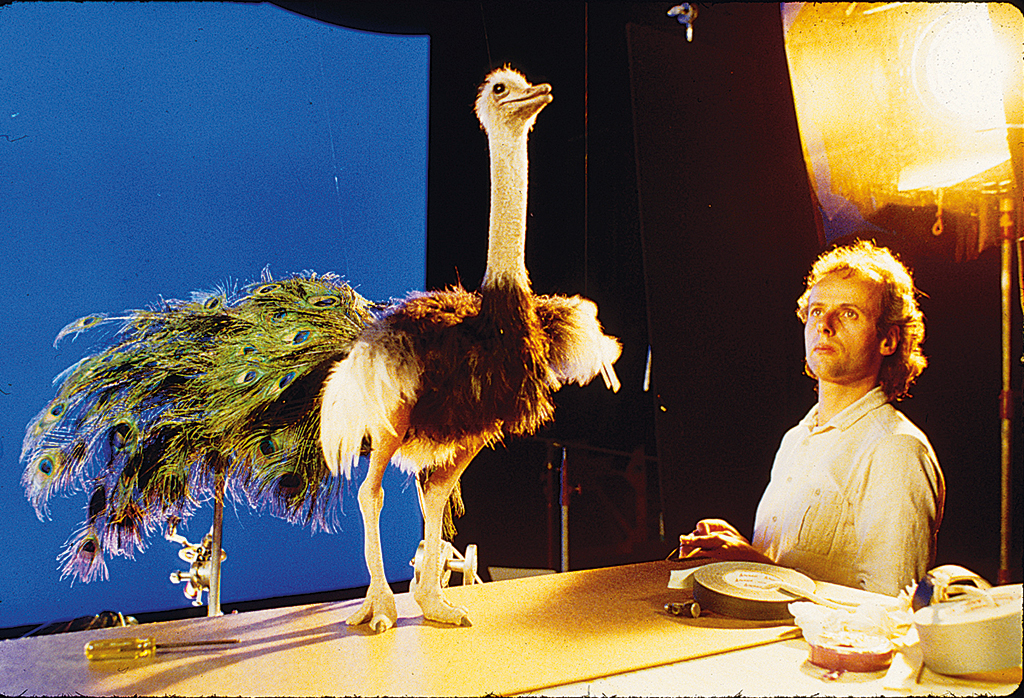

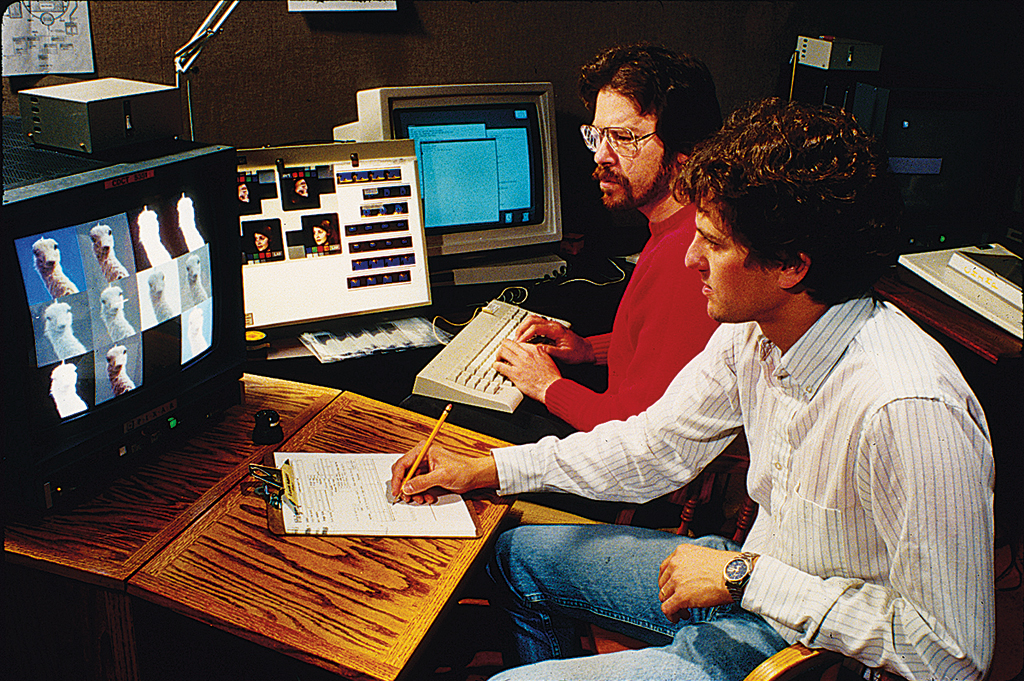

Willow’s most well-known visual effect – a magical transition sequence in which several animals such as a goat, ostrich, peacock, tortoise and a tiger blend between each other and then into actress Patricia Hayes – was also a landmark one in computer graphics and digital visual effects history. It introduced the film-going world to the concept of ‘morphing’, or then, ‘morfing’, since ILM’s toolset was called the MORF system.

MORF enabled smooth transitions (‘metamorphosis’) between key features of the different animals and actress in a single shot. Its developer at ILM, Doug Smythe, drew on research done at NYIT by Tom Brigham to design the software. The two would ultimately go on to be awarded a Technical Achievement Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for MORF.

Today, such a sequence would likely involve the animation of completely computer-generated animals. But at the time, crafting creatures and also dealing with fur and human hair was near impossible to achieve photorealistically. So a decision was made to mostly film articulated puppets and the actor separately on bluescreen and handle the transitions as 2D blends.

MORF worked by overlaying two separate grids on two different images – say a tortoise (the source) and a tiger (the destination). “You would go to various key frames throughout your sequence and then drag the grid points around,” explains Smythe, noting that matching key features was important.

“Then we had an alternate view where we kept the same image on the top, but then the bottom image became a timeline-type thing where you could pick any of the control dots at the corners of the mesh and see the timeline of how that would move and adjust it with a few key frame points to adjust the timing curve of how that particular point would change from the source color to the destination color.” MORF allowed digital artists to also have certain parts of the image change earlier than another part, enabling certain body parts to shrink or grow or even disappear during the morph. It originally ran on Sun workstations connected to Pixar Image Computers.

The tool became an important part of ILM’s visual effects arsenal, later finding use for the gruesome death scene of a Nazi sympathizer in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, several transformations in Terminator 2: Judgment Day, and transitions in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country.