By PAULA PARISI

By PAULA PARISI

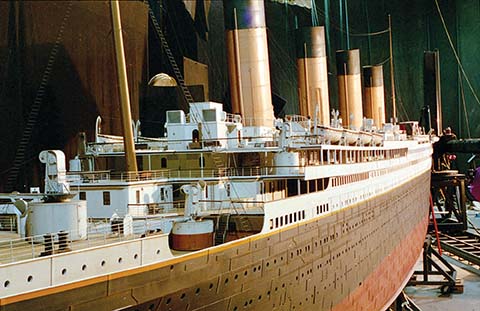

Digital Titanic on a digital sea created by Digital Domain for the 1997 film. Legato earned an Academy Award for his work on Titanic. (Photo copyright © 1997 Twentieth Century Fox. All Rights Reserved)

Rob Legato, ASC, didn’t set out to revolutionize an entire industry, he was just trying to make movies in away that felt intuitive to him. Trained as a cinematographer, that meant the freedom to try to change shots based on what he saw through a camera viewfinder, rather than adhering rigidly to storyboards created by an artist far removed from the set.

Legato’s career, during which he won three Academy Awards for Best Visual Effects for James Cameron’s 1997 Titanic, 2011’s Hugo and 2016’s The Jungle Book, has been dedicated to dissolving the wall between production and post, creating a new filmmaking vocabulary around virtual cameras and virtual sets. His techniques are now being adopted by others, as the live action and digital worlds blend. The changes upend decades of established practice where visual effects were rigidly dictated by storyboards and digital renderings created far from the set and costly to change.

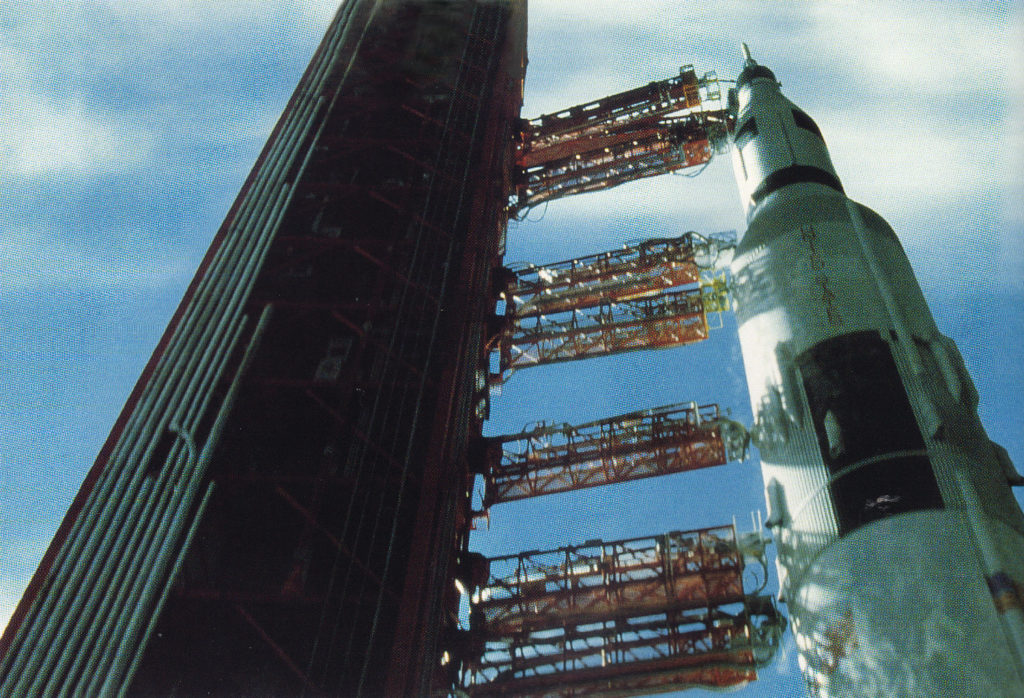

For Legato, the tectonic shift began with the “pan-and-tile” system he created to template the rocket launch for Ron Howard’s Apollo 13 in 1995 (for which he received an Academy Award nomination). Having endured previous frustrations, where he was restricted in his VFX camera moves by photography of the live-action plates, he undertook a series of “generic” angles on Cape Canaveral that would allow for more options when he later constructed the shot using a combination of CG and live elements. He refined and expanded his techniques to the point where 14 years later he presented it to Cameron as a viable means of directing virtual actors in real time on the set of Avatar. (Although Legato is credited as “virtual production conceived by,” he was not part of the Avatar production team, choosing to continue his collaboration with Martin Scorsese instead).

“Even if it’s a visual effect, it still has this off-handed life to it, kind of like when dialogue works really well it feels like the actors are saying it for the first time. It’s fresh, it’s alive, it’s natural. The same holds true for shooting.”

— Rob Legato, ASC

Legato, ASC, created the “pan-and-tile” system to template the rocket launch for Ron Howard’s Apollo 13. He captured a series of “generic” angles on Cape Canaveral that allowed for more options when he later constructed the shot using a combination of CG and live elements. (Photos copyright © 1995 Universal Pictures. All Rights Reserved.)

Legato, ASC, created the “pan-and-tile” system to template the rocket launch for Ron Howard’s Apollo 13. He captured a series of “generic” angles on Cape Canaveral that allowed for more options when he later constructed the shot using a combination of CG and live elements. (Photos copyright © 1995 Universal Pictures. All Rights Reserved.)Legato credits Cameron with funding him to develop a “large-scale version” of the simulcam system that made The Jungle Book possible.

Further advances meant when he joined Favreau in 2014 to start The Jungle Book, the director would be able to live-direct one actor whose performance was being captured photographically along- side a cast of virtual actors on an entirely digital set. With The Lion King (slated for 2019 release), on which Legato is Visual Effects Supervisor, the techniques will leap forward once again.

“I was going for something more improvisational and lifelike, and not so studied,” recalls Legato, who had just returned from a field trip to Africa with The Jungle Book director Jon Favreau, for pre-production on The Lion King. “Visual effects sequences can have a stiffness about them, because they’re created in dark rooms, sometimes halfway around the world, by CG artists who may or may not have live-action reference footage.

“It’s like, had they known what the three shots before it would have felt like, with music, they might have made that fifth one different. But you can’t do that if you’re executing a storyboard and everything just gets cut together later by a third person, the editor.” The result, in Legato’s opinion, was effects that seemed “disembodied from the film.”

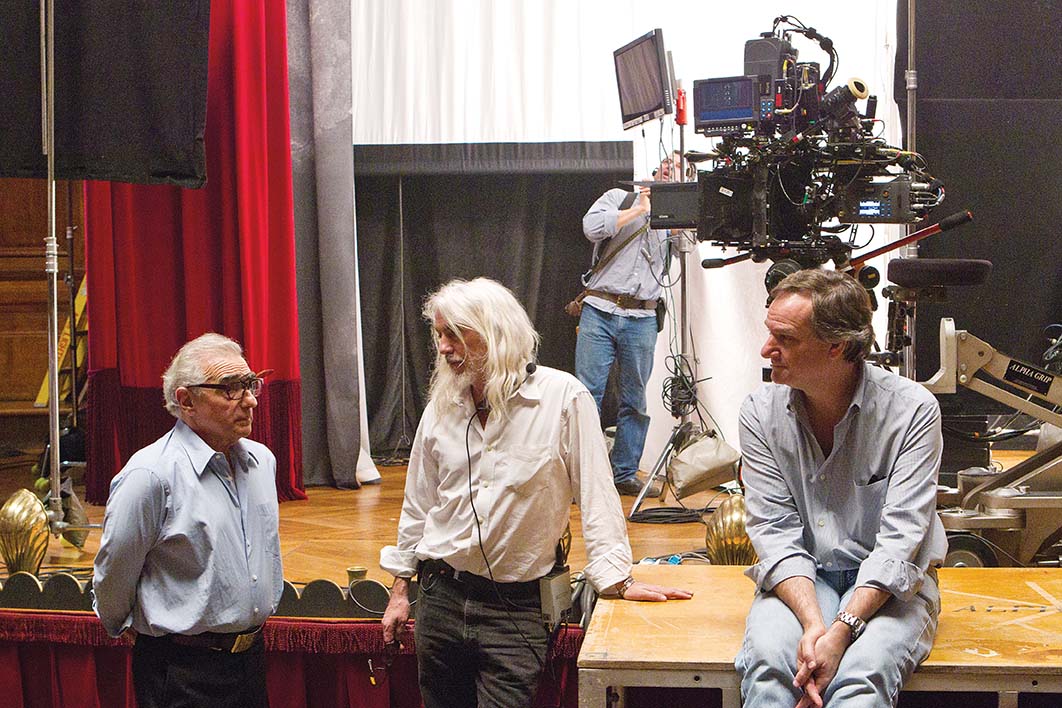

Legato at work on The Jungle Book, for which he received an Academy Award in 2017. (Photo credit: Glen Wilson. Copyright © 2014 Disney Enterprises, Inc. All Rights Reserved.)

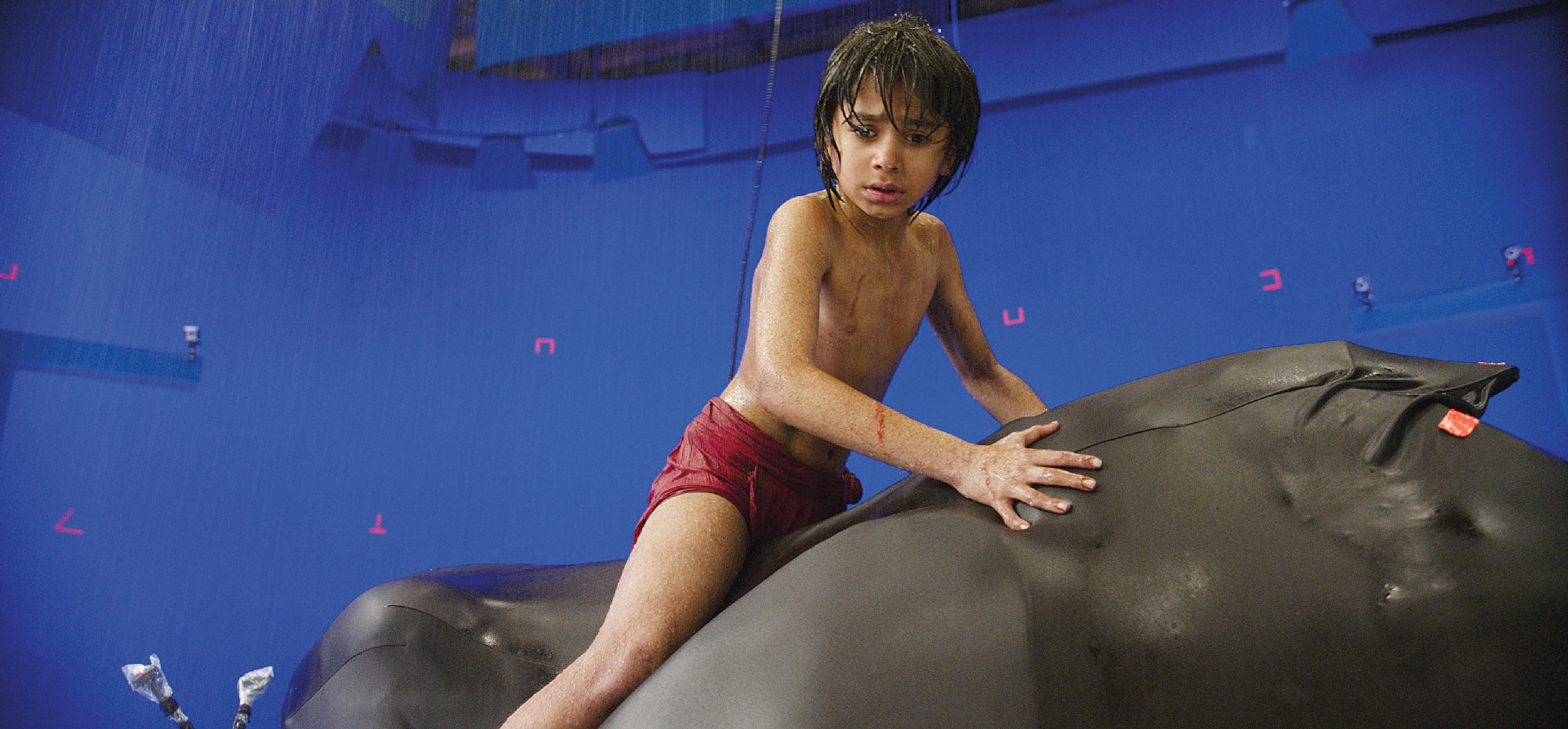

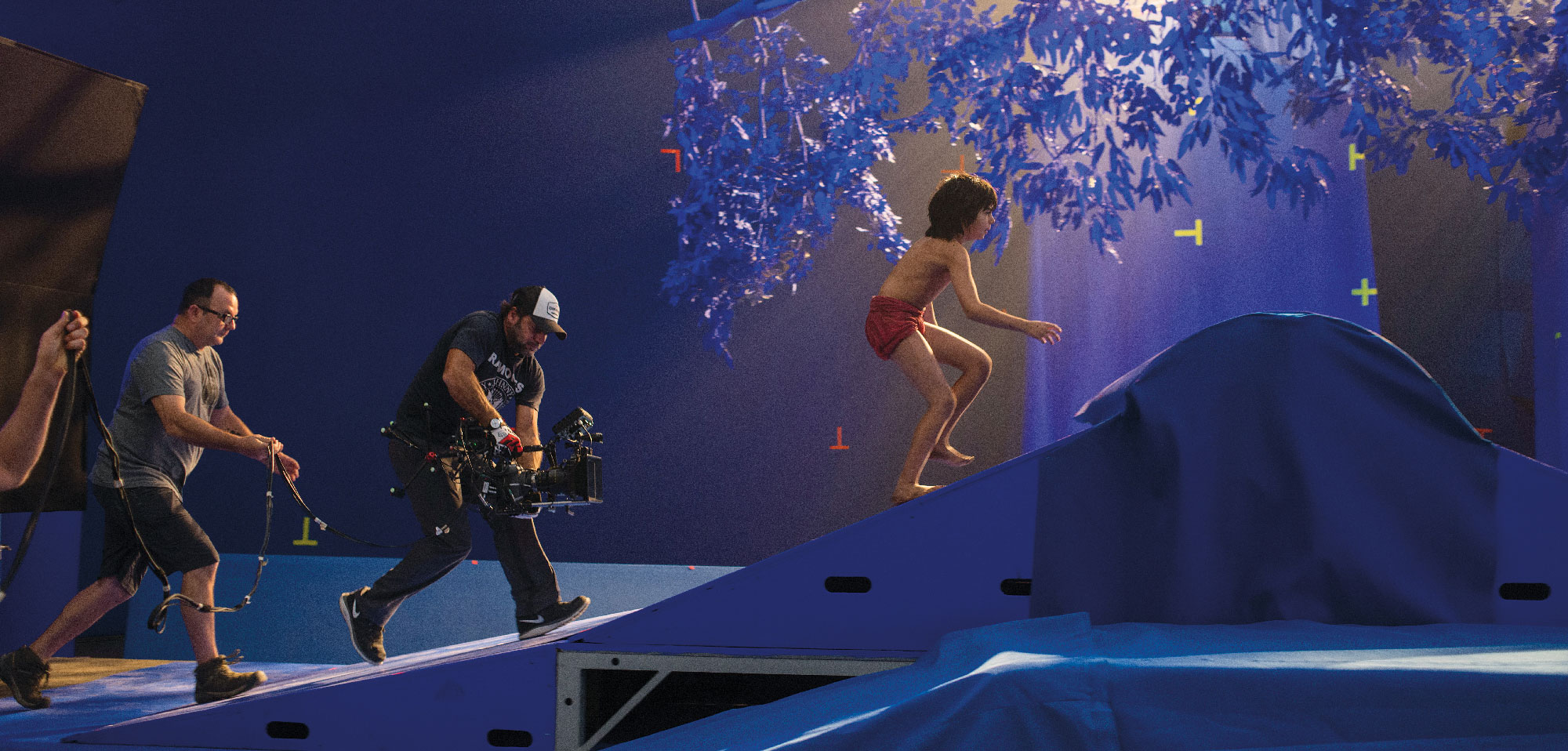

For The Jungle Book, the idea was to have an infinite jungle set in downtown Los Angeles, for purposes of creative control and so the filmmakers didn’t have to endure the hardships of a remote location.

The need for lifelike talking animals was another complicating factor. Legato, Visual Effects Supervisor and second- unit director on the film, was charged with creating a workflow that was to be essentially identical to shooting a live-action movie. He accomplished this in several steps, the first being to work with Favreau to template the shots, a process he calls “visualizing the movie,” as distinct from “pre-viz.” “Previsualization has a cartoon connotation, and is usually done by an outside house,” says Legato, who creates his own visualizations as part of his effects process. “The discipline and commitment to this system is what made The Jungle Book so special,” Legato says. “The whole movie was shot exactly like a live-action film.”

For starters, the visualization was created by Legato not by mousing around a 3D computer environment populated by CG characters, but by connecting a virtual camera that he moved through physical space, approximating the controls on the Arri Alexa that would be used on set. This visualized world is very specific. “We know if the set is 18-feet out from the wall that there is going to be a crane positioned here and an extension arm there. Then we execute that vision.” The big advantage was that when Legato was working in that visualized world, he could experiment with different possibilities to figure out what worked best, some- thing that becomes if not impossible, certainly impractical when a computer artist is building scenes based on storyboards, and changing a camera angle can cost tens of thousands of dollars.

“Because I’m a second unit director, I like to stage things for the camera, and what I stage for the camera is really for how it’s going to be cut together for a sequence. So my brain is always in that mode. I see the shot before me, and as I’m moving it’s telling me how to frame and how to do all of these things.” The result is that even though the final images are captured according to the visualized blueprint, the results are looser because it was mapped in a more intuitive style. “So even if it’s a visual effect, it still has this off-handed life to it, kind of like when dialogue works really well it feels like the actors are saying it for the first time. It’s fresh, it’s alive, it’s natural. The same holds true for shooting.”

For The Jungle Book, Legato helped Favreau capture “the inspiration of the moment, so it would feel like this scene is really beautiful because the sun is here, and the actor with the animals over there makes a great composition. It feels great for the movie, not for the effect.”

Shooting took place on a giant bluescreen stage at Los Angeles Center Studios, where the parameters of the virtual sets were digitally mapped onto the stage. Both Favreau’s cameras and the actors had motion sensors attached, so their movements could be conformed in the virtual environment and displayed on computers in real time.

For The Jungle Book, the idea was to have an infinite jungle set in downtown Los Angeles, for purposes of creative control and so the filmmakers didn’t have to endure the hardships of a remote location. (Photo copyright © 2014 Disney Enterprises, Inc. All Rights Reserved.)

The animal performances were powered by actors digitally assigned a walk cycle, or through the manipulation of motion-sensitized objects. “If they take a step, the four-legged creature takes a step. If they walk fast, the creature walks fast. There was an analog person, capable of taking direction, standing in for the creature.” The same held true for the virtual camera. Legato and Director of Photography Bill Pope, ASC, could map moves by tracking sensor-equipped platforms –a crane, a dolly, a helicopter or a hand-held camera – capturing those moves in the virtual set..

Since there are no live-action characters in The Lion King, there is talk of having the actors powering the animals wearing VR headsets as they are performance-captured on the virtual set – effectively transporting them in the virtual world so they can react more immediately to each other and the environment. Legato declined to comment. “The system keeps improving no matter what the next film, which happens to be The Lion King.”

Legato creates his visualizations using Autodesk’s MotionBuilder. While he foresees Autodesk’s Maya software and Pixar’s Renderman as continuing to be the standard bearers for rendering, he thinks the hacked videogame engines that have powered these on-set virtual worlds is due for a major overhaul.

“That’s not really what (the game engines) were made for,” he says, more elaborate visions dancing in his head. Like any artist, Legato excelled at using the tools at hand to advance his craft. He credits the directors with whom he’s worked with backing his play. “They like this system because it’s directable,” he says of the enthusiastic reception his techniques have received from Cameron, Howard, Scorsese and others.

“In terms of the shot planning, the middleman is removed. You’re doing it virtually, it’s real-time. It’s getting more and more handsome as computers get faster and game engines get better.” He estimates Favreau stuck with the visualized camera moves for 75%-80% of the film. For the 20%-25% percent that Favreau did want to change, he let Legato go all-in to make it great.

“That’s where something like this really shines – you can focus the extra effort.”

Legato is not a fan of dividing effects work up among a dozen houses. “For The Jungle Book, there was MPC and Weta. Weta did the ape scenes, about 400 shots. And MPC did the other 1,200.

“I was delighted Disney let us do it that way,” he says, “because some studios insist on breaking the work apart. They think they can save money and retain more control that way, but what it does is create chaos that you’re trying to manage through triage.”

Things have certainly come a long way since he got his start out of college as a commercial producer. “I didn’t have any special interest in effects,” he admits. “I was just interested in movie- making, but the whole thing about movies is it’s all illusory – you shoot one angle, then you cut to another angle, and it looks like they’re in the same room, but they may not be. It could have been shot at a completely different time. I’ve always loved editing.”

Shutter Island lighthouse.

Legato would go on to membership in both the Local 600 International Cinematographer’s Guild and Local 700, the Motion Picture Editors Guild, but not before establishing himself as a VFX whiz at Robert Abel & Associates, the legendary commercial house that made its name pioneering electronic effects.

Legato was hired for his live-action expertise. “I worked on a stage in the back, but I’d go over to where the visual effects guys were playing, and I’d make suggestions, to the point where they’d said, ‘you should do it.’ Eventually, I did.” From there he moved into episodic television, first MGM’s Twilight Zone series, then at Paramount, where he not only helmed visual effects, but got to direct the occasional episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine.

Television effects were just moving from optical to electronics. “You could only do a few optical effects for a weekly series, because the process was slow. But if you did them digitally – or at the time, the analog/digital way – you could do quite a bit more. That was just coming into vogue, and I was one of the few people who bridged the gap.”

In 1993, he was recruited by Digital Domain, a visionary new feature-film visual effects house launched by Cameron, makeup effects wizard Stan Winston and Scott Ross, former head of Industrial Light & Magic. It was there that the light bulb went off while working with Ron Howard on Apollo 13. In 1999, Legato left to work for Sony Pictures Imageworks, before going freelance to work with Martin Scorsese on the 2004 Howard Hughes biopic The Aviator.

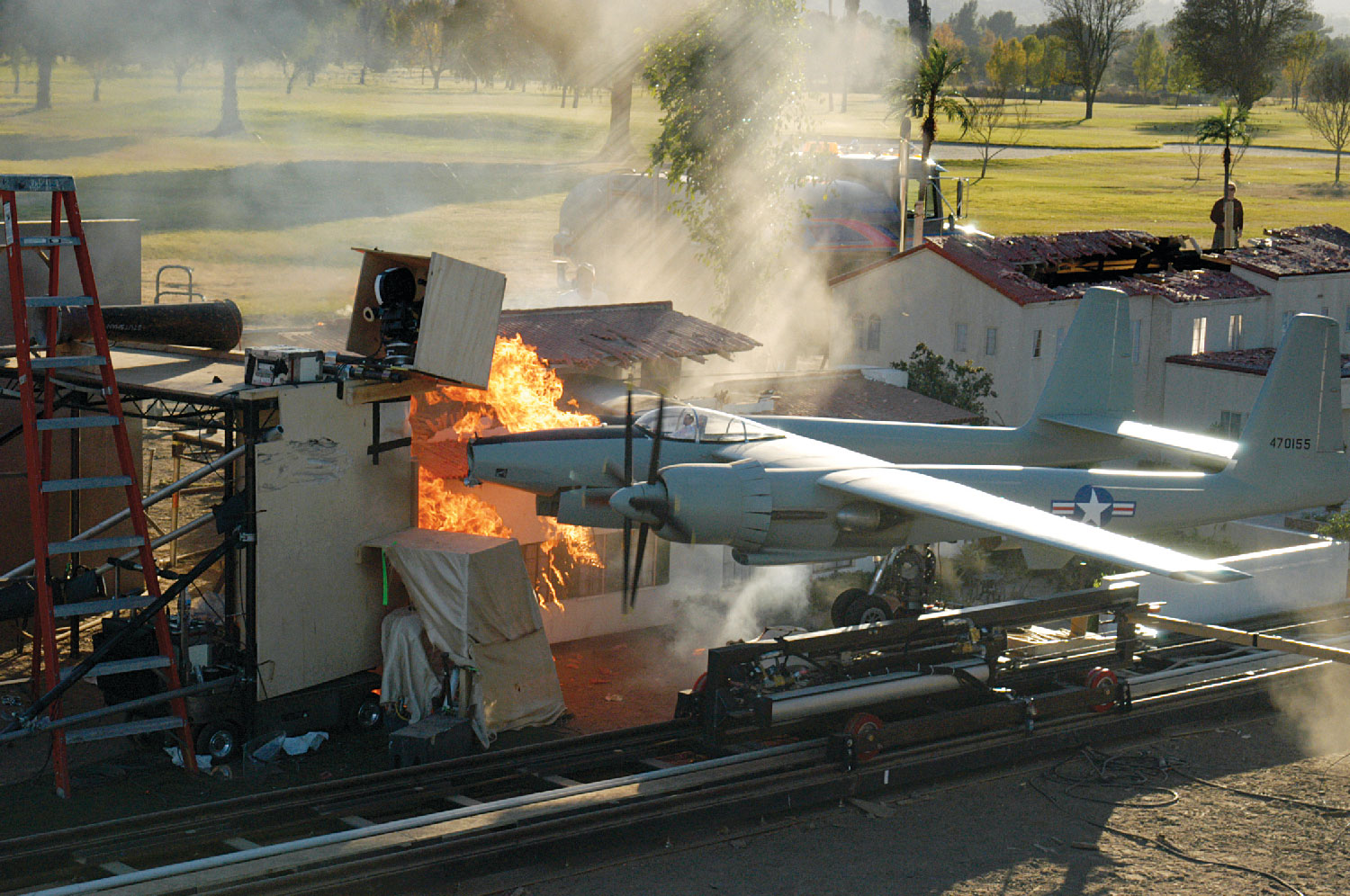

He cites Hughes’s plane crash in Beverly Hills as another pivotal stage in his evolution. “I had them create a pan-and-tilt wheel in the computer, so once we had an animation I could operate the camera. That allowed it to be ‘live,’ so I could react off what I was seeing, like a real cameraman would do on a stage.” As with the Apollo rocket launch, it became one of Legato’s signature second- unit action scenes.

“Between the editing and the camerawork, it became a very fluid way of telling a story. A filmmaker shoots dailies, trying to get proper coverage to give you the different options, then you put it together editorially and it makes it an exciting sequence. Because this was an expensive model we were crashing, I had one chance to shoot it live.” Since “action scenes come alive in the editing,” Legato said he didn’t want to be caught “discovering” the best way to compile the material after it had been shot, without the means to go back and try different options. “I had to practice. I practiced on the computer, and I got a pretty decent sequence that felt like it really moved. Then when I went to photograph, it had a life to it that felt like it was traditionally photographed.”

“I didn’t have any special interest in effects. I was just interested in moviemaking, but the whole thing about movies is it’s all illusory – you shoot one angle, then you cut to another angle, and it looks like they’re in the same room, but they may not be. It could have been shot at a completely different time. I’ve always loved editing.”

— Rob Legato, ASC

The brave new world he’s helped to usher in is opening up possibilities on many fronts. “We’re building tools to bridge the digital and live-action worlds. That’s ultimately what Jim [Cameron] responded to when I showed him the virtual way. Now he can direct the movie. He can hand-hold the camera, shoot the shot he wants to do, edit it himself, literally in the next minute – you shoot it and then you go cut it together. He’s in a computer directing a film, as opposed to directing a bunch of artists trying to emulate the spontaneity of real life. So things have really changed.”