By TREVOR HOGG

By TREVOR HOGG

Coco tells the story about a young boy who aspires to become a musician against the wishes of his family and embarks on a magical adventure where he encounters a famous deceased relative. There was no doubt as to the setting of the 19th feature from Pixar Animation Studios.

“The reason for Coco being set in Mexico is related to the idea of making a film based on the Day of the Dead,” explains Coco co-director and writer Adrian Molina. “We were inspired by the opportunity in animation to create this land of the ancestors and the emotional story you can tell that leads into the holiday.” Research trips to museums, markets, plazas, workshops, churches, haciendas and cemeteries were vital in the development of the project. “Within weeks of me first pitching this story to John Lasseter [in 2011] we were all on planes heading down to Mexico,” recalls Coco director Lee Unkrich. “We traveled all over the country, from Mexico City to Oaxaca, down to small towns in the state of Michoacán, to document the look of these different urban and rural areas, and give us inspiration for creating our world. It was also critical for us to spend time with different families as they celebrated Día de los Muertos, and observe their family traditions and dynamics.

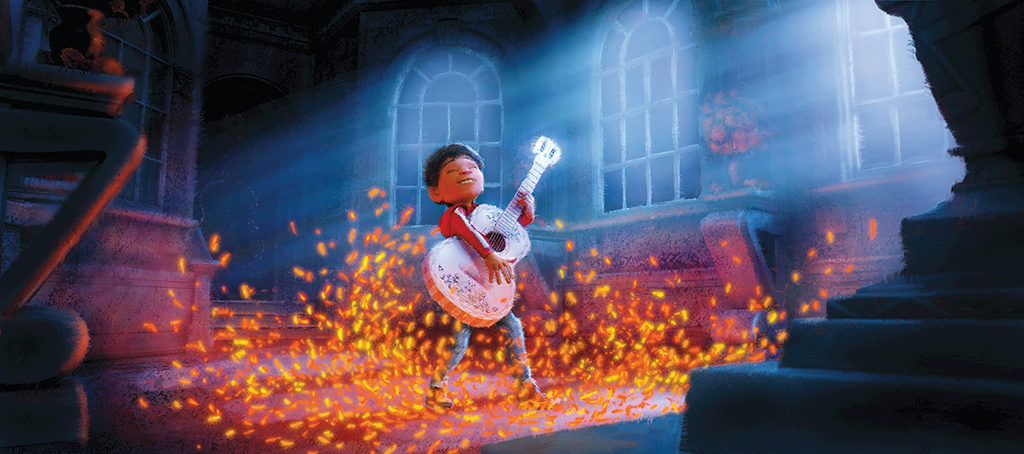

“We could have easily gone down a route like ‘Starbones’ coffee shops on every corner, but I wanted to keep everything grounded and influenced directly by Mexican architecture and life,” remarks Unkrich. “That being said, we have lots of hidden skeletons everywhere as well as skull faces both within the architecture and the way that these different towers in the Land of the Dead line up.” The visual styles of Land of the Living and Land of the Dead contrast, says Unkrich. “Everything is flat and horizontal in this little town of Santa Cecilia in which Miguel lives. When he goes to the Land of the Dead we suddenly introduce all of these vibrant colors. It’s our version of Dorothy going to the Land of Oz. We also designed the Land of the Dead to be vertical. It’s made up of tall towers.”

In the Land of the Dead are towers constructed by the newly arrived souls who build them upwards in the architectural style of their time. “At the base of these towers are pyramids and at the top there is modern construction going on,” remarks Supervising Technical Director David Ryu. “We created a diversity of buildings through time and stacked them up on top of each other to create this look. From an execution perspective these things are big. We had this system of taking these buildings, finding ones that match and instancing them together so that we only paid for it once; and doing that not only inside a single tower but across towers.”

One of the elements that was halfway deployed on Pixar’s Cars 3 but used throughout Coco is a technology called Flat Sets which allows Presto to think of dense complicated sets as single entities. “You’re not loading a tower, another building, a vehicle and a headlight, as the system thinks about it as one thing,” Ryu says. “ “Optionally, if an animator needed to go in and move any stuff they can click on a button, crack it open and make it real.”

Various types of lights are found in the Land of the Dead from pin lights on buildings to street lamps to headlights to windows reflecting lights. “Having this many lights was hard,” admits Ryu. “We put these test scenes together and had to talk to the RenderMan guys on how to make this stuff scale. They partnered with Intel to optimize the core light picking algorithms. We worked with them to further optimize the process of figuring which 10 lights out of eight million are important to the thing that you’re actually rendering. It’s influenced by where you’re looking, how far away the lights are, if you are being blocked by shadow or not, how bright the lights are, and by the shape of the lights. The RenderMan guys went in and optimized that part of the code a ton for us.”

“The reason for Coco being set in Mexico is related to the idea of making a film based on the Day of the Dead. We were inspired by the opportunity in animation to create this land of the ancestors and the emotional story that you can tell that leads into the holiday.”

—Adrian Molina, Coco Co-director/Writer

“Everything is flat and horizontal in this little town of Santa Cecilia in which Miguel lives. When he goes to the Land of the Dead we suddenly introduce all of these vibrant colors. It’s our version of Dorothy going to the Land of Oz.”

—Lee Unkrich, Coco Director

“We had never done skeleton characters at Pixar before, so a lot of time was spent looking at how skeletons had been used in other animation, from early Disney cartoons to Ray Harryhausen to Tim Burton. It was all done with an eye towards being as appealing as possible and at the same time we had to create characters that could emote and people could care about. That’s what led us to make decisions like allowing our skeletons to have eyeballs. Eyes are the windows to the soul and I couldn’t imagine playing emotional scenes with a character that had empty eye sockets.”

—Lee Unkrich, Coco Director

“We had never done skeleton characters at Pixar before, so a lot of time was spent looking at how skeletons had been used in other animation, from early Disney cartoons to Ray Harryhausen to Tim Burton,” remarks Unkrich. “It was all done with an eye towards being as appealing as possible. At the same time, we had to create characters that could emote and people could care about. That’s what led us to make decisions like allowing our skeletons to have eyeballs. Eyes are the windows to the soul and I couldn’t imagine playing emotional scenes with a character that had empty eye sockets.” A decision was made to have lips and angular mouth shapes to suggest a hard surface. “We couldn’t stay with a separated jawbone and skull area look because we needed to be able to get some clear mouth shapes and be able to articulate dialogue,” recalls Supervising Animator Gini Santos. “The eyeballs and eyelids were treated as one malleable organic piece so we shaped the eye sockets to work like eyebrows in creating shapes of expressions.”

“Skeletons are humanoid, so we were able to use underlying rigs for arms, legs, fingers, bones, eyes and mouths,” notes Ryu. “The skeletons can take off their arms and put their hands on their heads, and take off their heads and throw them to the next guy. That’s part of the fun of the world. We had to augment the human rig to be able to detach.”

Some rules needed to be put in place to ensure an aspect of believability. “The bones could separate because of impact or excitement,” explains Santos. “That’s our skeleton version of squash and stretch. It was more difficult because we required a lot more control.” An automated tool called Kingpin was utilized to animate a ‘jiggle’ to the bones to give them a sense of looseness. Clothes worn by the skeletons come from the time period in which they lived. “Our cloth simulator went through a basic overhaul,” states Ryu. “Our tools team put in new collision algorithms and lots of pieces of new technology to make simulations of higher density cloth meshes against this skinny bone geometry robust. We ran a bunch of tests in the beginning when we had skeletons against a skirt with a petticoat and blouse on top of it, and stuff would blow up. After this overhaul that stuff was super stable which enabled us to push it.”

“There are some scenes in the movie with tens of thousands of skeleton crowds in them and we have a Houdini-based system for simulating these crowds,” adds Ryu. “We built a system that could take each individual thing in a shot and analyze how big it ever gets onscreen. If it is super faraway it isn’t very important, but if it gets up close it’s super important. We auto-generated a bunch of levels of detail for every single crowd character for every single animation cycle. This system would figure out how important everything was onscreen and then automatically assign these levels of details.”

Most of the effects in Coco are based on taking a cultural idiom of a holiday and turning that into a real thing, like a path on the ground [of marigold petals] turns into this large bridge,” remarks Effects Supervisor Michael O’Brien. “Where the characters interact is designed like somebody walking through real petals. Then as you move away and see the structures of the bridge, those are designed to be more magical. There’s this inner light pulsing through it and a lot of motion happens ancillary to the trusses that are all intentional. The top surface is what’s given to animation, crowds and layout so they know what to shoot for. Then the bridge is grown around those structures. The trellises we would erode into the columns that were below to get the shapes that we wanted, and the glowing patterns are all added. There’s a dual res noise that makes a nice wind pattern that tweaks the orientation of the petals along the edge and side of the bridge to give a sense that they’re solid but still able to move and have dynamics.”

One of the characters that went through a few iterations and had the most discussions about was Mama Imelda, Miguel’s great great-grandmother, who we see in photos in the Land of the Living but in person in the Land of the Dead,” remarks Molina. “There was a lot of talk about what her character was motivated by, and what she was protecting in terms of her family and why she creates these rules that are trouble for Miguel. How she holds herself, the way she does her hair and the outfits she wears. We talked about a woman who was once vulnerable and got hurt because her heart was open – even down to the design of her dress and shoulders to give a sense of armoring up and of being strong for the sake of her family. There was also a lot of talk about what visually sells this character who is protecting her family.”

“Skeletons are humanoid, so we were able to use underlying rigs for arms, legs, fingers, bones, eyes and mouths. The skeletons can take off their arms and put their hands on their heads, and take off their heads and throw them to the next guy. That’s part of the fun of the world. We had to augment the human rig to be able to detach.”

—David Ryu, Supervising Technical Director

The ghost effect consists of five to six layers, says O’Brien. “They’re all done subtly because they’re not meant to detract from the animation. The layers are highlighted a lot more when Miguel passes through somebody with each having their own color. A glow happens around the face and another for the clothes. There are some wispy bits that came off of each layer that are dialed independently.”

The canine companion of Miguel transitions into an alebrije (a fantastical creature). “That was difficult for us because it’s full screen when Dante transforms from a black dog into this colorful spirit animal with wings,” explains O’Brien. “We wanted the transition to feel like it’s welling up inside of him, not running across the surface. It was a tough look for us because you’re essentially trying to get a single surface scatter thing to feel like it’s starting to glow and feel natural. We drew a lot from the patterns that are painted on him and tried to have those drive the animation.” There are not many effects in the Land of the Living. “We did a lot of ambient things like candles, drinks on tables, and a bouquet of flowers that people carry [which was complicated].”

Among the voice cast for Coco are Edward James Olmos, Gael García Bernal, Benjamin Bratt, Cheech Marin, Ana Ofelia Murguía, Sofía Espinosa and Alanna Ubach. “I’m proud that we have an all-Latino cast,” states Producer Darla Anderson. “Lee knows what he wants in terms of creating the texture and acting in the film. It was an arduous and interesting experience as we have lots of characters and family members. We needed each one to have a unique voice. The voice cast infused their own spirit into the characters.”

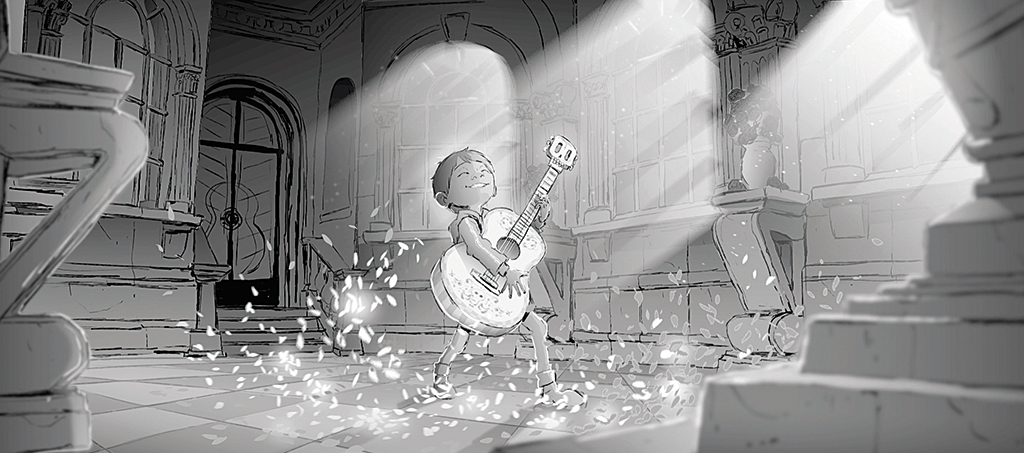

A storyboard of the pivotal moment when Miguel Rivera strums the guitar that once belonged to his idol Ernesto de la Cruz. A signature motif of the skull is found in the design of the guitar head.

“From the beginning it was important to me that the characters were really playing the musical instruments in the movie,” reveals Unkrich. “I wanted them to be playing the right chord, strumming strings in the right way, and to do that we did have to record a lot of the music well in advance and film lots of reference video of musicians playing the instruments so that the animators could make sure they created animation which was believable and accurate in how the music would be played.” Along with a score composed by Michael Giacchino, Adrian Molina collaborated with Germaine Franco, Bobby Lopez and Kristen Anderson-Lopez to write songs that helped to push the story forward. “We wanted to do a broad variety of Mexican music,” notes Molina. “We had this opportunity to lean into Mexican and indigenous instruments to create music that says a lot about our story and characters in a unique way.

“The look of the film is spectacular but the moments which are most core and beautiful are the quiet ones which take you by surprise,” observes Molina. “I hope that people feel the same way.” A scene on a gondola traveling through the Land of the Dead stands out to Ryu. “It’s a shot that’s all about how huge and beautiful the world is.” O’Brien is pleased with the unique effects. “The spectacle of the Marigold Bridge, the ghosts, Dante’s transition and the Final Death are all things that people haven’t seen before.” The quest for a guitar is a wonderful moment for Gini Santos. “Miguel and Hector visit this character named Chicharron. It’s the setting, how Hector sings this song, and the lighting is so beautiful. I feel like here in the United States we have our own take on Día de los Muertos. The film taught me a lot about what that celebration is to Mexicans.” Anderson is pleased with the end result. “I’m proud of the team and what we’ve managed to do. Coco is unique, but yet feels like it belongs in the pantheon of all the other Pixar films.”