By IAN FAILES

By IAN FAILES

Visual effects studios are constantly being asked to deliver more shots more quickly than ever before. It can be a major challenge to get effects out the door for review, work to final them, and then deal with inevitable changes. Which is why Sony Pictures Imageworks Visual Effects Supervisor Sue Rowe decided to tackle things slightly differently when she took on the challenge of helping to craft the third act of Jon Turteltaub’s The Meg, the tale of a previously undiscovered prehistoric giant shark, or megalodon.

“When the Production Supervisor Adrian De Wet and Visual Effects Producer Steve Garrad came to us, they knew this third act was going to be tricky because story points in the climax of a film are always developing, and they knew they would need a really powerful engine behind them to get that work done,” Rowe tells VFX Voice.

“So the deal we entered into at the beginning was, ‘Hey, we’re going to give you perhaps 400 shots, and we want you to turn them around really fast and then give them to editorial, and then we’re going to hone it down from there.’”

To enable Imageworks to turn around so many shots for the third act of The Meg so quickly, Rowe employed several new methods. The first was to rely on Maya’s Viewport 2.0 to work on high-quality but still early versions of the shots directly in the viewport without the need to render.

“The reason I really liked it is that it was super fast,” states Rowe. “You can add fog as depth and you can put spotlights in. You see, when you distill everything down that you need for an underwater movie, it’s pretty much about bubbles and particulates.”

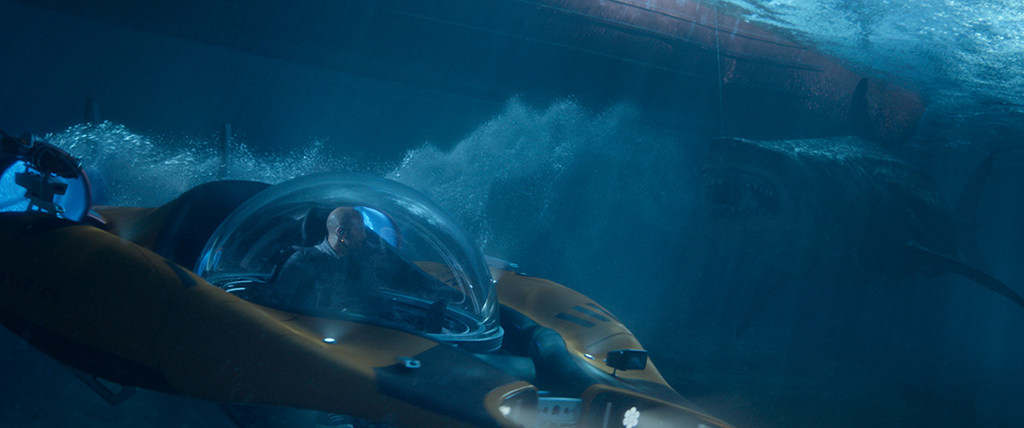

By using Viewport 2.0, Imageworks could turn around versions quickly in a kind of ‘post-vis’ workflow. This included shots that ultimately did not make the final cut of the film. Artists would quickly roto and matchmove plate photography of the actors filmed in a water tank (against an underwater bluescreen) and then hand that over to animation and layout. There was no lighting or compositing done for these early deliveries, but the results were more than good enough for the filmmakers to review shots, after which Imageworks could move onto generating finals with more precision through its traditional pipeline.

“This is what I always say to people who start out in the industry – the computer might solve it in a certain way, but if it doesn’t look how the director ultimately wants it to look, then we just have to make sure it fits into the movie.”

—Sue Rowe, Visual Effects Supervisor

Another weapon in Imageworks’ arsenal was Ziva Dynamics’ muscle- and skin-simulation plugin, Ziva VFX. The software takes a physically-based approached, which means more accurate looking skin sliding and movement straight out of the plugin.

“If you build your skeleton accurately, that’s the starting point,” says Rowe. “The system the guys have written will then make the muscles and skin move in the correct way so you don’t have any intersections and it won’t fold in on itself. What was interesting was, it’s also flexible. So if I wanted to have the shoulder of the shark shudder, but in a really extreme way, we could push it to that if we wanted.

“The idea that we employed for Meg was,” adds Rowe, “if you ever look at a thoroughbred horse and how their muscle shakes, it ripples down their body. And from that you know that this is a really muscular, powerful character. So we said, let’s do the same for the Meg. You’ll see a little twitch in the muscle or the gills. We definitely amplified those things using Ziva.”

In addition to the shark itself, Imageworks had to imagine an underwater environment, parts of which required vast amounts of coral. The studio had developed a scattering tool for plant life on Kingsman: The Golden Circle called Sprout, and this was also employed on The Meg for the underwater coral.

“We built multiple types of coral, different types of rock and sand, and we had some fish in there as well. And then we clustered them altogether and covered it in coral with Sprout. The cool thing about it was, I’d sit down with my effects artist, and they would show me a first pass of it all being laid out, and we were able to interact with the coral, scale them up, scale them down and move things about. It’s a really cool tool.”

—Sue Rowe, Visual Effects Supervisor

“It’s a way of building indices or replicas of objects very quickly,” explains Rowe. “We built multiple types of coral, different types of rock and sand, and we had some fish in there as well. And then we clustered them altogether and covered it in coral with Sprout. The cool thing about it was, I’d sit down with my effects artist, and they would show me a first pass of it all being laid out, and we were able to interact with the coral, scale them up, scale them down and move things about. It’s a really cool tool.”

Imageworks had been able to craft a realistic shark and a realistic underwater environment, but there was still another element that was needed to help sell the shots: bubbles. More specifically, it was the cavitation of bubbles around submarines, propellers, and even the Meg itself.

Rowe and her team looked at a multitude of cavitation reference (cavitation actually occurs when the propellers cause the water to boil and get ejected out the back). Noticing that the cavitation trail tends to be quite elongated, this was how Imageworks originally approached simulations in Houdini. However, at some point, notes Rowe, “the director saw a few shots where the cavitation actually rose up, rather than shoot out straight. He really liked this look, even though it wasn’t necessarily physically correct.”

“If you build your skeleton accurately, that’s the starting point. The system the guys have written will then make the muscles and skin move in the correct way so you don’t have any intersections and it won’t fold in on itself. What was interesting was, it’s also flexible. So if I wanted to have the shoulder of the shark shudder, but in a really extreme way, we could push it to that if we wanted.”

—Sue Rowe, Visual Effects Supervisor

That meant Imageworks had to re-do several of its original bubble and cavitation simulations. Rowe thinks the ultimate result was much more engaging. “This is what I always say to people who start out in the industry – the computer might solve it in a certain way, but if it doesn’t look how the director ultimately wants it to look, then we just have to make sure it fits into the movie.”

Similarly, there were moments when the filmmakers felt that some underwater shots were still missing something. Rowe realized the ‘secret source’ were things she called ‘streams’ – bubbles that matched the tail movement of the Meg, or even crept out of the creature’s nose. “It just created this slight sense of movement underwater that we really needed,” says Rowe. “I remember sitting in dailies and going, ‘Give me more bubbles, give me more, more, more, more bubbles!’”