By CHRIS McGOWAN

Jay Worth, VFX Supervisor (All images copyright © 2018 HBO)

“What we come back to is what’s going to help tell the story the best.”

—Jay Worth, VFX Supervisor

By CHRIS McGOWAN

“What we come back to is what’s going to help tell the story the best.”

—Jay Worth, VFX Supervisor

Michael Crichton, a master of the science fiction thriller, often explored cutting-edge technology and the question “What could possibly go wrong?” in his novels and the movies based on them. In HBO’s Westworld TV series, based on Crichton’s 1973 movie of the same name, the android hosts of a future amusement park malfunction in ways both mundane and menacing. By the end of the first season, Dolores, Maeve and other hosts had become self-aware and turned on their human keepers. “The park has gone a little haywire,” as VFX Supervisor Jay Worth puts it.

The finale, “The Bicameral Mind,” won the 2017 Emmy for Outstanding Special Visual Effects for Worth, Elizabeth Castro (VFX Coordinator), Joe Wehmeyer (On-Set VFX Supervisor), Eric Levin-Hatz (VFX Compositor), Bobo Skipper (ILP VFX Supervisor), Gustav Ahrén (Modeling Lead), Paul Ghezzo (CG Supervisor, CoSA VFX), Mitchell S. Drain (VFX Supervisor, Shade VFX) and Michael Lantieri (Special Effects Coordinator).

Worth’s team also includes: Joe Wehmeyer (On-Set VFX Supervisor), Bruce Branit (On-Set VFX Supervisor), Jacqueline VandenBussche (Lead VFX Coordinator), Melanie Tucker (VFX Coordinator), Jill Paget (VFX Editor) and Sarah Bush (VFX Assistant Editor). Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy co-created the Westworld TV series and serve as executive producers along with Bad Robot’s J.J. Abrams and Bryan Burk.

A Super Bowl commercial in February – HBO’s first in 20 years – made it clear that much havoc was yet to come in season two of Westworld. “Jonah [Co-creator/writer/director Jonathan Nolan] had this great idea, a vision of these bulls running through our lab set, wild beasts in a scientific area,” Worth recalls. One of the bull’s hides is partly torn off, revealing a black exoskeleton and wiring.

“Dolores’s robot body in the season finale was one of the sequences that we focused on the most, and we brought that back in a lot of different ways, such as with the bull,” says Worth. “The team at Double Negative worked around the clock taking our design elements from ILP. Double Negative built out the interior of this robot bull, and it just looks amazing.”

With technology having gone off the tracks, this year has offered additional VFX thrills and built on what has gone before. Seasons one and two together have offered many startling visual effects. In season one, VFX rejuvenated Dr. Robert Ford (Anthony Hopkins) by 40 years and peered into the head of “Robot Boy” and the inner workings of the heroine Dolores, among other feats. Season two built out Westworld, introduced Shogun World and explored the bigger picture of the park’s history. It also presented CG tigers and the peculiar drone hosts. In both years, Westworld portrayed a wide range of possible android behavior, from the more mechanical to the apparently human.

Worth and his team have overseen the VFX efforts, with help from such vendors in seasons one and two as CoSA VFX, ILP (Important Looking Pirates), Rhythm & Hues Studios, Double Negative, Fractured FX, Pixomondo, Shade VFX, Chickenbone Effects, Deep Water FX, Skulley Effects, bot vfx, Yafka Studio, Revolt 33 Studios and Crafty Apes VFX.

“Our team of vendors is pretty amazing. In season two we extended it out to crank through this volume of shots because our schedule was a little more compressed than it was last year,” says Worth.

The second season has also explored the ongoing puzzles of the park´s location, what lies outside it, and its underlying corporate purpose. Worth enjoyed trying “to figure out where our people go, with our flashbacks to the present day or near future, what our present reality looks like and where that might be.

“We didn’t base it on a specific city, but it feels like a presentreality, near-future, interesting place. Once again [it was] more in the world-building category but, as always, we were just trying to make it look as real as possible.”

“We didn’t base it on a specific city, but it feels like a present-reality, near-future, interesting place. Once again [it was] more in the world-building category but, as always, we were just trying to make it look as real as possible.”

—Jay Worth, VFX Supervisor

Comments Worth, “We went back to things we loved. I felt like in season one we had enough time and we had enough freedom to really craft things the way we wanted to, to tell the story that Jonah and Lisa wanted to tell. It didn’t feel like we were ever hamstrung or having to avoid or to cut around, or didn’t quite fully realize something we talked about. [So it was great] to bring back some of those things.”

Worth joined the VFX big leagues with a little help from his life-long pal VFX Supervisor Kevin Blank. “In 2005, I was walking home from work in Chicago when I called him and he said, ‘Do you want to work on Alias?’ Six weeks later I was in a cornfield working on the final season of Alias as a VFX Coordinator. I fell in love with the production side of VFX instantly,” says Worth.

Part of his education came from working with J.J. Abrams as a VFX Supervisor on Fringe. He met Abrams once in passing and had no prior relationship with him up to that point. “However, that started a two-year email conversation back and forth on Season 1 and 2 of Fringe, where J.J. reviewed and approved almost all of the shots. We didn’t have a single phone call or in-person meeting – it was all over email. I would send emails almost every night and we would go back and forth with thoughts and ideas. That was my VFX school really – figuring out how to describe things, to distill ideas, to explain and execute abstract concepts.”

Worth has worked with Abrams and Bad Robot since then, as well as with Jonathan Nolan, beginning with Person of Interest (2011-2016). Some of Worth’s other projects include 11.22.63, Almost Human, Revolution and Cloverfield. He had received five Emmy nominations prior to winning for Westworld in 2017.

“[In season two] we lean away from making the hosts more robotic because we want to show the humanity of these characters. We show them as more mechanical when they’re old or malfunctioning. But when they’re struggling through their emotional state, and cycling through different things, we do almost nothing.”

—Jay Worth, VFX Supervisor

Worth spent a great deal of time brainstorming future iterations of androids with Nolan. “We dug into everything in terms of design on Westworld – but how the hosts are built was a big part of the show and the visual language of the show. Additionally, we had many discussions about the different generations of hosts. That was probably the concept that occupied most of our discussions – how could this happen, what efficiencies could we create in the idea behind the process, and how would that impact the visual design?

“We had many discussions about skeletal procedures, organ printing and stuffing, muscle weaving, skin dip tanks – all of it was designed throughout and planned. We really worked at designing every part of the process so that if you only see one part, it feels like it is part of a whole.

“What we come back to is what’s going to help tell the story the best,” says Worth. “In season one there were a lot of hosts that malfunctioned. And we had Old Bill, who was not necessarily malfunctioning but was an older model.” Old Bill was given an animatronic look, “but he was a very specific host. Then we had some hosts like the sheriff that malfunctioned, a little more sporadic in his movement, and then we had hosts that just struggled, like Abernathy [Dolores´s father] or Bernard. When they were just glitching, as we called it, we did almost nothing because their performances were so amazing.”

In season two “we lean away from making the hosts more robotic because we want to show the humanity of these characters. We show them as more mechanical when they’re old or malfunctioning. But when they’re struggling through their emotional state, and cycling through different things, we do almost nothing.”

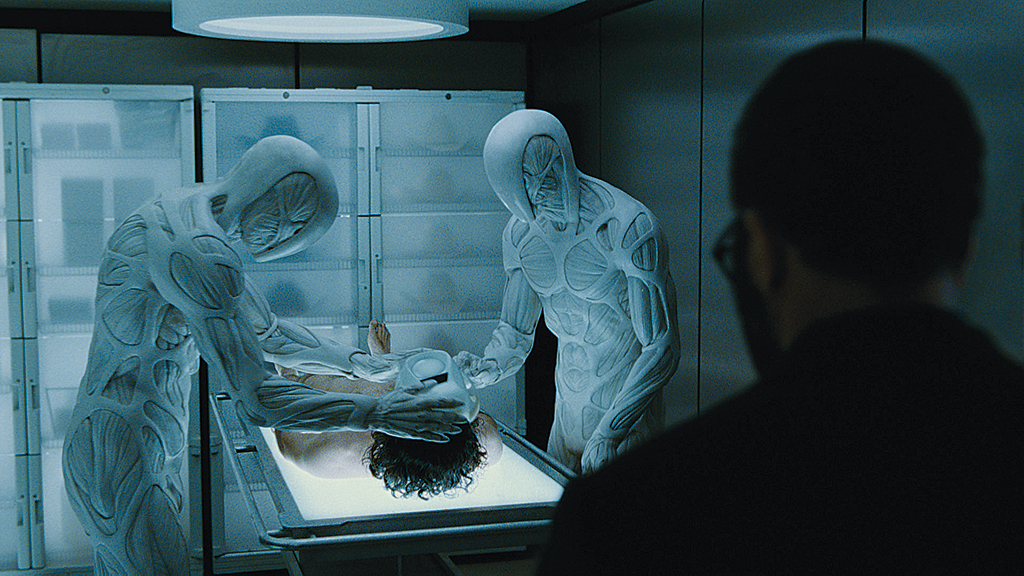

Season two introduced a creepy new all-white robot. “The drone hosts are down in another facility; they function as sort of worker bees and it was fun to build out that idea. That was one of those situations where you read the script for the first time and you weren’t quite sure what you were going to make. It’s this host that doesn’t have any skin and doesn’t have any pigment and it’s all muscle.

“Justin Raleigh and his team at Fractured FX really did an amazing job. They were able to find a very slim person to put on the [drone host] suit; it looks like normal proportions when he puts on the suit. From the FX standpoint, all we did was cleanup on the suit itself. Where there’s a crease or where it doesn’t look like it’s their skin-cleanup on makeup effects.”

There were new animal characters as well. “We did a tiger sequence for episode three, which obviously had its challenges, doing full CG tigers on a TV schedule,” says Worth. “But the team at Rhythm & Hues busted it out and killed it as always. It was a lot of fun to work with them and bring this to life.”

Different progressions of Westworld’s Interactive Map are also seen in Season 2. “We tried to find ways of showing this technology that’s not doing as well. What does the map look like when it’s malfunctioning? What does the map look like when there’s a battle in the world? We built up the technology in season one. It was based on a projector system but we always wanted it not looking like a projector, not looking like a TV screen and not looking like a hologram. So we had a map upon which we projected real time imagery of this landscape and it was all based on correct lighting, so at different times of day the shadows across the map would be different, with a three-dimensional quality. This season is about what happens when the map goes south. The systems are all shut down and because of that the map breaks, the map comes back online, the map dies.” Worth had to figure out what that looks like “from a story perspective and from a visual effects perspective as well.”

“We did a tiger sequence for episode three, which obviously had its challenges, doing full CG tigers on a TV schedule. But the team at Rhythm & Hues busted it out and killed it as always. It was a lot of fun to work with them and bring this to life.”

—Jay Worth, VFX Supervisor

“Jonah [co-creator/writer/director Jonathan Nolan] had this great idea, a vision of these bulls running through our lab set, wild beasts in a scientific area. Dolores’ robot body in the season finale was one of the sequences that we focused on the most, and we brought that back in a lot of different ways, such as with the bull. The team at Double Negative worked around the clock taking our design elements from ILP. Double Negative built out the interior of this robot bull, and it just looks amazing.”

—Jay Worth, VFX Supervisor

Shogun World was featured prominently in season two and “required some element shoots. When I read about the shogun battle, I knew that with that many people getting sliced with katanas we were going to need to have specific elements that were tailor-made for the show.” Fortunately, squib shoots got a green

light. “This season we were able to do a very robust elements shoot that we wanted to do for season one but weren’t able to. We fired off hundreds of squibs and muzzle flashes, every one of our weapons, so it brings a reality to the texture of things and it’s not a CG element or out of the tool kit. We shot them with specific lighting in mind and specific angles in mind.”

Production Designer Howard Cummings and his team built the Shogun World and Protagoras sets for season two. Protagoras was the biggest set piece of the year from the FX standpoint. “That and what we’re calling The Gate in episode 10,” adds Worth. “The finale is really the culmination of everything in terms of set extensions, building out facilities, as well as ambition.”

In the story, everything in the Westworld theme park has been designed, which adds to the real-world labor of creating it. “It makes all the difference. The challenge we have is that every inch of every frame has to be designed. This goes for every department. There really aren’t many places you can shoot where you just dress somebody, light them and shoot. Every single frame in our show is designed. What timeline might we be in, where are we, who is this character? It isn’t just that it is a theme park – the entire world we have created is very specific and defined.

“So we are looking at every single frame,” Worth states. “Whether it be a con trail in the sky or a slight variation in a host from the normal day-to-day that has to be unified to every possible variation in set design and continuity – it is a complete production effort to bring this [to] life. Thankfully we have an amazing group of collaborators – we all have each other’s back and work incredibly well together to pull off this vision.”

The original Westworld, directed by Crichton, pioneered the use of digital effects in feature films when it used two total minutes of pixelization for an android POV. Twenty years later, Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (based on Crichton’s novel) was another landmark with its CG dinosaurs.

Asked what Crichton might have thought of the new Westworld, Worth responds, “I hope and think that he would have loved it. I think it’s taking this idea that he had of what does it mean to be human and what does it mean to be in control or not, and how to use technology to do that. Obviously, he was fascinated with the idea of telling stories that pushed the boundaries of how you can tell them visually. To have some small connection to what he was able to envision is really a lot of fun, to be part of the world that he created.”