By TREVOR HOGG

By TREVOR HOGG

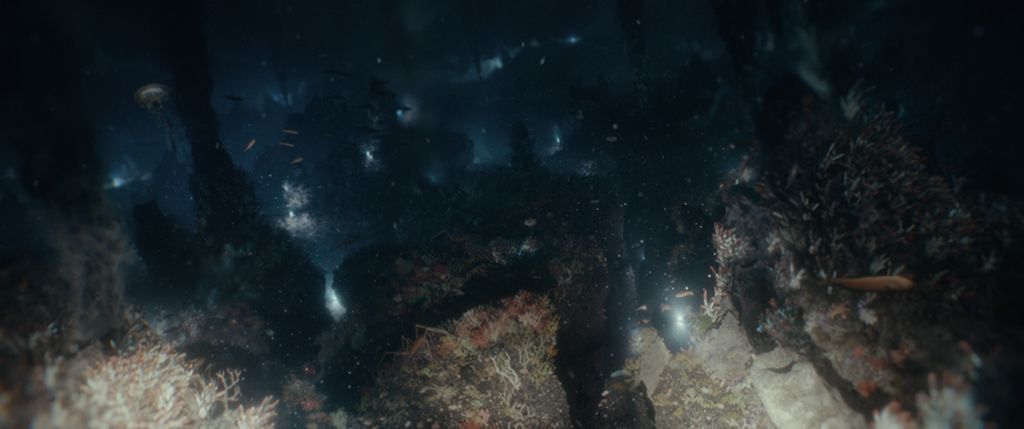

As epic as it was for Scanline VFX to create a 75-foot prehistorical shark for The Meg, another monumental task was to produce the underwater environment of the Mariana Trench, which is a crescent-shaped trough 1,580 miles and 43 miles wide with a maximum-known depth of 36,070 feet. DNEG utilized customized procedural tools in order to populate the vast ocean floor environment as well as to control the amount of haze. Not counting the terrain, there were over 30 different assets of tube worms, coral, jellyfish, fish, spider crabs, isopods and hydrothermal vents that needed to be created.

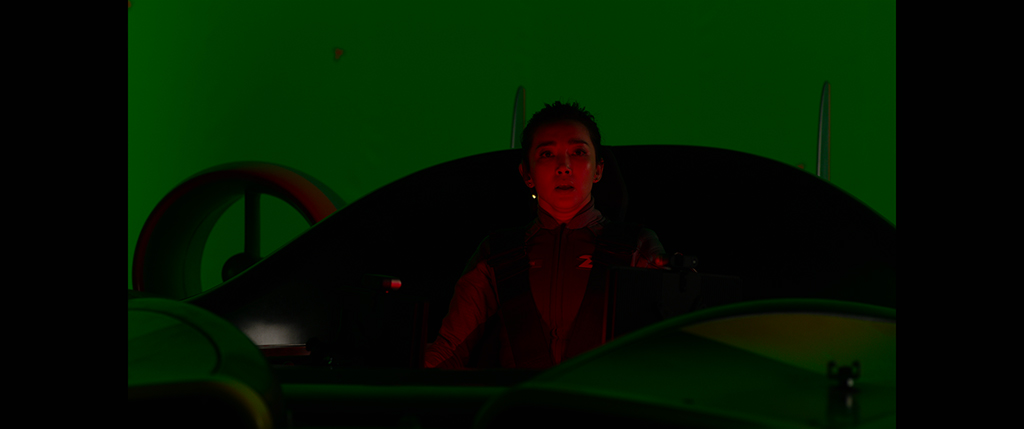

“Previs was done for the Mariana Trench discovery sequence, so what we did was set up a blocking pass and plot out the path of camera and submersibles through the environment with a rough shape of the Trench,” explains DNEG VFX Supervisor Raymond Chen.

“We roughed out the forms, did some modelling, and made some camera adjustments. There was some back and forth. In terms of populating the Trench, a lot of that was built as a procedural system, which was quite handy, because it allowed us to adapt to camera changes or moving things around. The vents were scattered in Houdini, and we had these big cloud simulations coming from them. For the vents themselves, there were multiple variations and different sizes. There ended up being a dozen different types with corresponding smoke simulations coming off of them.

“Previs was done for the Mariana Trench discovery sequence, so what we did was set up a blocking pass and plot out the path of camera and submersibles through the environment with a rough shape of the Trench”

—Raymond Chen, VFX Supervisor, DNEG

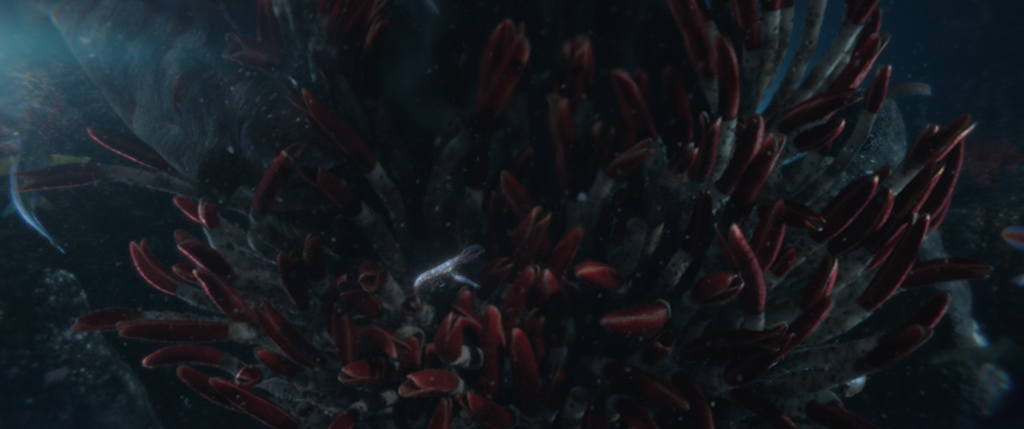

“We built all of the tube worms and animal life. We had a procedural system where the tube worms would be populated in and around the vents because this is what happens in nature – they feed off of the chemical processes that are around the vent. In our scattering simulation, we tried to keep the populations clustered together.”

—Raymond Chen, VFX Supervisor, DNEG

“We roughed out the forms, did some modelling, and made some camera adjustments. There was some back and forth. In terms of populating the Trench, a lot of that was built as a procedural system, which was quite handy, because it allowed us to adapt to camera changes or moving things around. The vents were scattered in Houdini, and we had these big cloud simulations coming from them. For the vents themselves, there were multiple variations and different sizes. There ended up being a dozen different types with corresponding smoke simulations coming off of them.

“Some of the vents had one exit point while others had two exit points,” Chen continues. “On top of that we built all of the tube worms and animal life. We had a procedural system where the tube worms would be populated in and around the vents because this is what happens in nature – they feed off of the chemical processes that are around the vent. In our scattering simulation, we tried to keep the populations clustered together. If you have a colony it spreads out, but there is a core or denser area.”

All of the creatures were based off of real species with a concept artist making slight adjustments to them. “The idea was that these had been locked off from the rest of the world, so they’re a slightly different evolutionary branch,” remarks Chen. “There is some wonderful deep-sea video footage of things like the Chimaera, Ghost shark or Wolf Eel. The giant squid was one of the more difficult ones because there’s not a lot of footage of it deep underwater.” The giant Pacific octopus was a useful reference. “There are lot of those in aquariums around the world. We looked at their tentacles and suckers, which were extrapolated to the giant squid.”

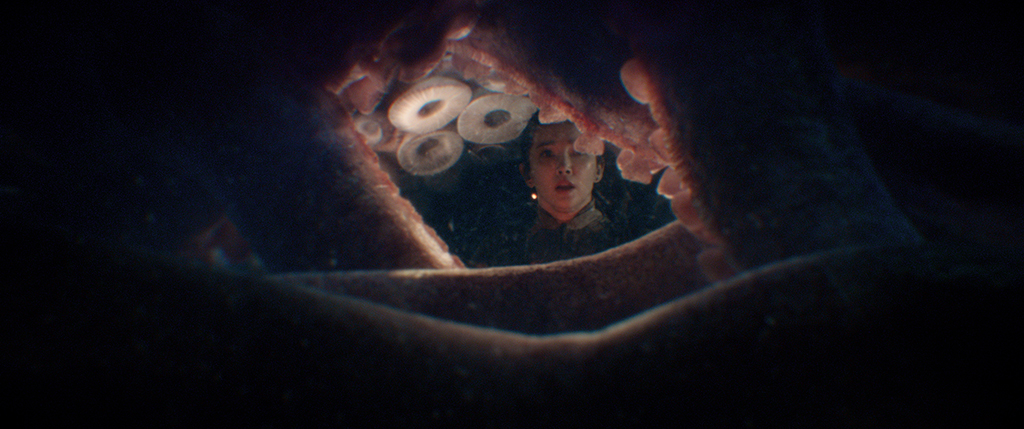

The rigging was complex for the massive creature that has no skeletal structure. “Anything that is like rope or a snake is incredibly difficult to rig,” Chen adds. “Then you have a creature here that has 10 tentacles. We see from inside the glider a giant tentacle slamming onto the glass dome. The suckers are right in your face. We worked on getting all of detail into the sucker and figured out its growth pattern. [Production VFX Supervisor] Adrian de Wet had an interesting image that he kept pointing to us to show the idea of contact and compression. It was a stock photo of a woman pressing her face up against a pane of glass. It was shot from the opposite side, so you can see her face smooshed up against the glass, as well as the color difference between the contact areas.”

“The first submersible launches deployable lights [resembling spherical Chinese lanterns] that are tethered to an anchor. The anchor goes to the seafloor with a light hovering 10 or 15 feet above it. That allows the filmmakers to say, ‘There’s our light source.’ … Having those deployable lights was a wonderful concept to being able to get light into the environment.”

—Raymond Chen, VFX Supervisor, DNEG

Since there can be no shafts of natural light down in the deep depths of the ocean, some artistic license was required when revealing the Mariana Trench. “The first submersible launches deployable lights [resembling spherical Chinese lanterns] that are tethered to an anchor,” states Chen. “The anchor goes to the seafloor with a light hovering 10 or 15 feet above it. That allows the filmmakers to say, ‘There’s our light source.’ We did have localized lights clustered around each of these dropped deployable lights. It also gave us an excuse to say, ‘There are some of these lights off screen, so we can get some ambient fill on the right side.’ A lot of decisions were driven by whatever director Jon Turteltaub needed to show. Having those deployable lights was a wonderful concept to get light into the environment.”

Judging the darkness was tricky, says Chen. “Being dark makes it scary, but that forced us to skirt the edge of reality. Artists would work at their desks and go, ‘This is the right level.’ But then in a screening room with no ambient light, it turned out to be a lot brighter than they thought it was. It was definitely an issue getting the light levels to be right.”

“Anything that is like rope or a snake is incredibly difficult to rig. Then you have a creature here that has 10 tentacles.”

—Raymond Chen, VFX Supervisor, DNEG

Read more about Double Negative’s VFX work in “Double Negative: Double Decades of Double Positives” here!

Read more about Double Negative’s VFX work in “Double Negative: Double Decades of Double Positives” here!