By IAN FAILES

By IAN FAILES

LED screens, practical stunts and sets, models and miniatures, restored archive footage and lots of invisible effects – they’re just some of the VFX techniques utilized in telling the story of Neil Armstrong’s (Ryan Gosling) 1969 moon landing in Damien Chazelle’s First Man.

Those ‘old-school’ effects methods, coupled with several new ones, were overseen by Visual Effects Supervisor Paul Lambert from DNEG, Special Effects Supervisor J.D. Schwalm and Miniature Effects Supervisor Ian Hunter. VFX Voice went behind the scenes to find out more.

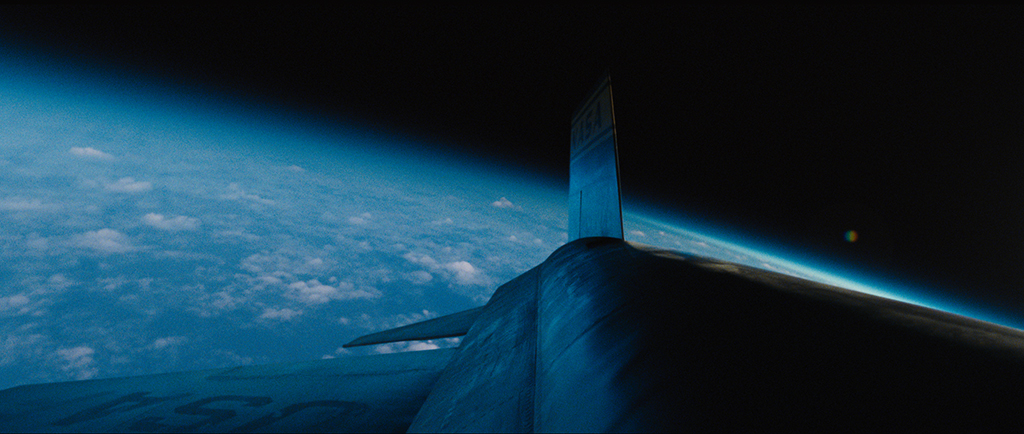

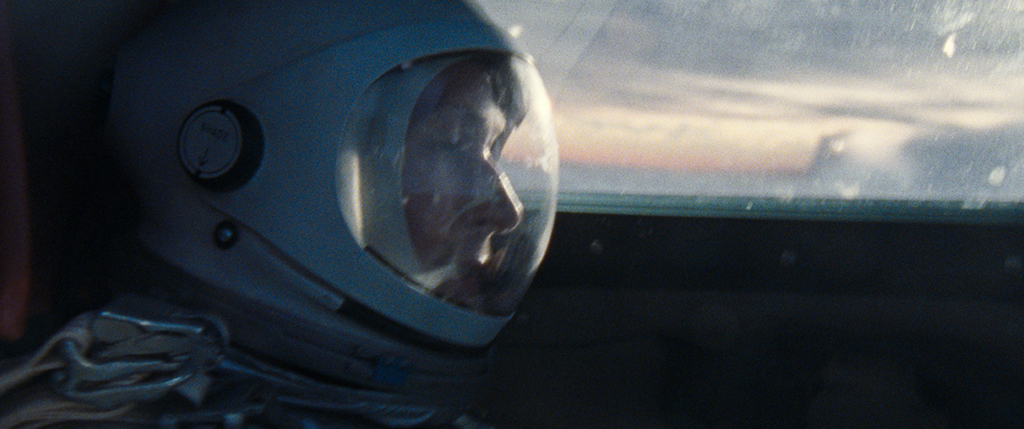

Several sequences in First Man featured astronauts fastened into cockpits, and the camera deliberately sticking to them or their direct point of view, or positioned as if fixed to the side of a jet or spacecraft fuselage. To help achieve these ‘fly-on-the-wall’ angles, the filmmakers looked to acquire realistic interactive lighting from skies or space backgrounds, and immerse the actors into the shots for as many in-camera shots as possible. For that, DNEG pre-rendered footage to be played on a giant 60 x 35-foot LED screen that wrapped 180 degrees around the filmed action.

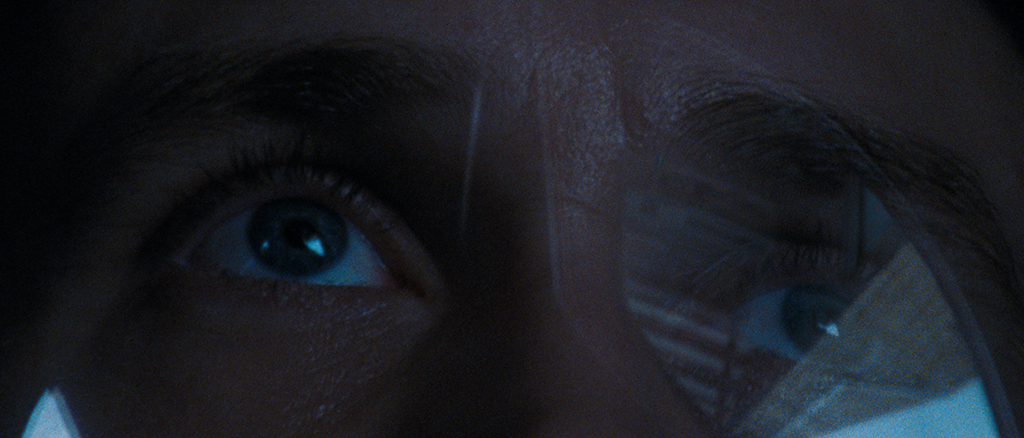

“In the X-15 shot where you see Neil bursting through the atmosphere and he sees the horizon for the first time, that reflection on his visor is the actual reflection from the LED screen, but also the reflection in his eyes. Coming from a compositing background myself, that’s actually a fairly complicated thing to get to look real, getting that complexity of a reflection in an eye. And because we spent the time at the beginning, we’re getting that for free.”

—Paul Lambert, Visual Effects Supervisor, DNEG

The footage – 90 minutes worth – took in helicopter and jet plates as reference would appear through canopies or portholes. It first gets seen in the film as Armstrong is making an upper atmosphere flight in a NASA X-15 and ‘bounces’ off the atmosphere.

“We had decided to go down this particular route because we wanted to not be using computer graphics throughout the entire film,” says Lambert, who also notes there had to be a match to the 16mm, 35mm and IMAX film as shot by DP Linus Sandgren. “The idea of having the backgrounds already prepped and rendered and then shot through the camera – that instantly gives you the right film patina, and you get the right grain, too.”

For shots of the actors in capsules or in spacecraft or the X-15, set pieces were mounted on 6-axis gimbals devised by Schwalm and his crew. With so much run-time of footage, scenes could play out in long takes (some lasting more than 10,000 frames). Initially, just front and side views for the LED screen were delivered, but Lambert soon realized that 360-degree images would be more optimal.

“What we ended up doing was rendering minutes and minutes worth of footage in a 360-degree VR kind of format. And the playback system allowed us to do rotations during filming. So we were even able to do color corrections and put in masks – it was the start of being able to interactively comp on set. It was a little bit clunky and we kept it to the basics, but the fact that we could do rotation was huge. You could turn around on set just by spinning the gimbal and then spinning the actual content on the screen.”

The LED screen also proved key in providing visor reflections and even reflections on dials inside spacecraft. At times, the actual pre-made backgrounds appearing outside cockpits or windows could be kept in the final shots. “For example,” says Lambert, “in the X-15 shot where you see Neil bursting through the atmosphere and he sees the horizon for the first time, that reflection on his visor is the actual reflection from the LED screen, but also the reflection in his eyes. Coming from a compositing background myself, that’s actually a fairly complicated thing to get to look real, getting that complexity of a reflection in an eye. And because we spent the time at the beginning, we’re getting that for free.”

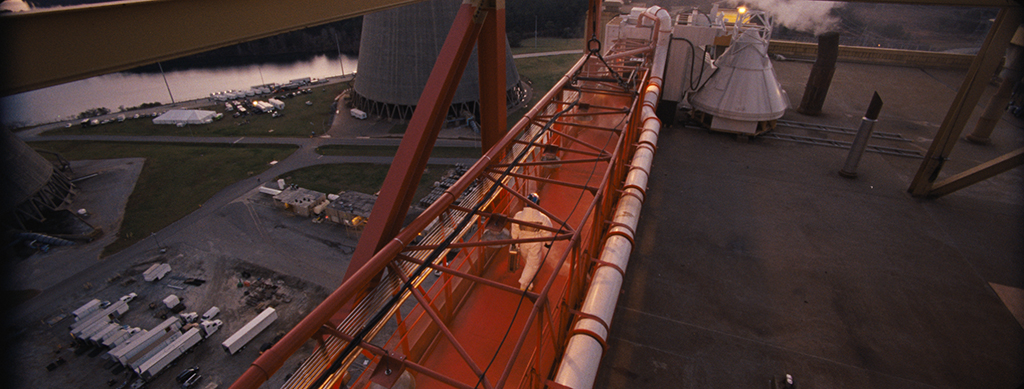

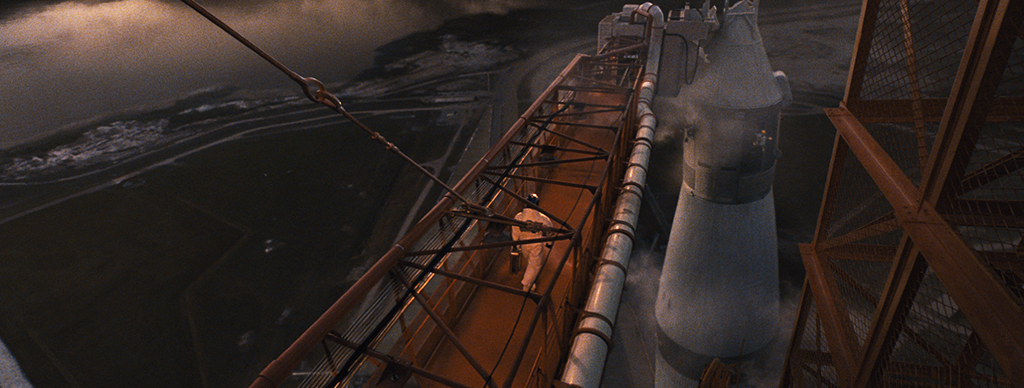

In space exploration history, NASA has amassed a huge archive of film reference of its launches and space journeys. So it was natural that the First Man filmmakers would take advantage of such footage. It was Chazelle’s wish that the space scenes in the film matched what people knew from the historical footage.

“He wasn’t interested in coming up with crazy camera moves where we would, say, sweep around the rocket,” discusses Lambert. “He wanted it all based on what people had seen before. And then, the more footage we pulled, the more I started to realize that we could essentially use some of this footage.”

Ultimately, DNEG replaced archival footage step by step with a visual effects-enhanced version. This started, in particular, with the views of engineering cameras, which often captured specific parts of a rocket as it began a launch, such as the exhaust or clamp, or a fin along its side.

“[Director Damien Chazelle] wasn’t interested in coming up with crazy camera moves where we would, say, sweep around the rocket. He wanted it all based on what people had seen before. And then, the more footage we pulled, the more I started to realize that we could essentially use some of this footage.”

—Paul Lambert, Visual Effects Supervisor, DNEG

But first that original footage had to be processed – a mammoth task in itself. “There was some footage that actually took us months and months to scan, because it was based on a NASA military-grade stock, which you couldn’t actually play back anymore,” notes Lambert. “It was only by chance that we came across an experimental scanner which was sprocketless, and we were able to scan this material.”

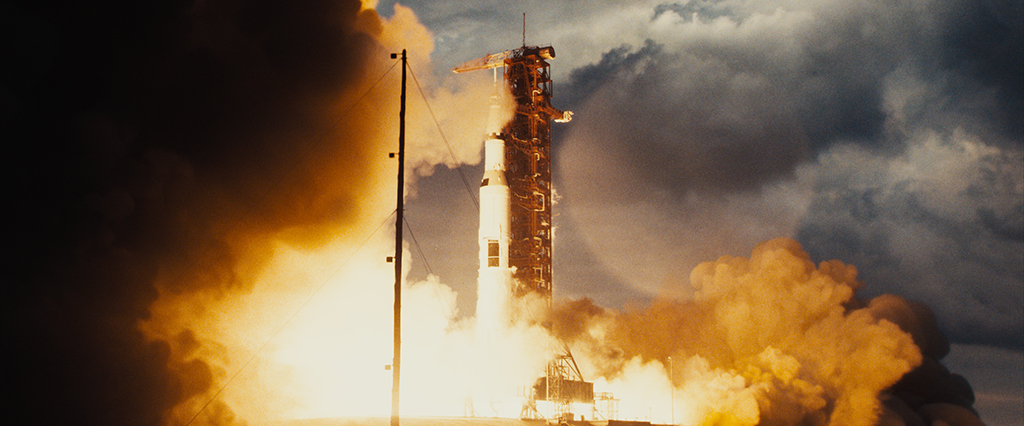

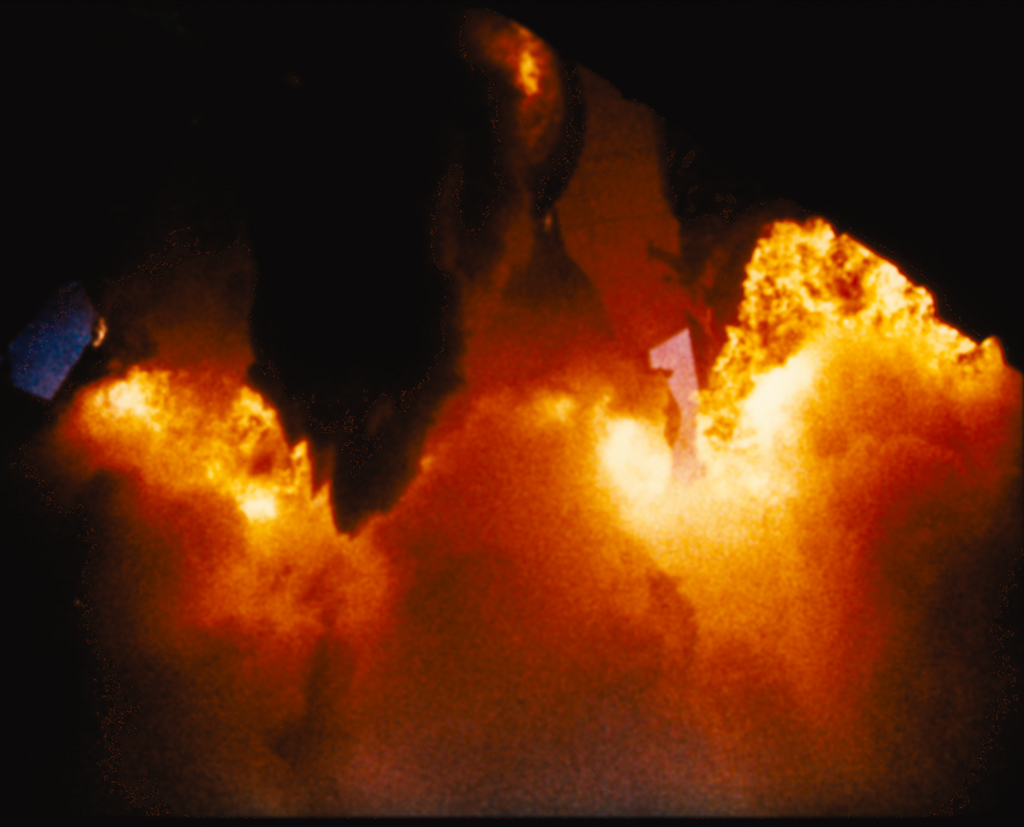

An example of the enhancement of archival footage was for a wide shot of the Saturn V rocket with two large plumes of smoke emanating from either side. The original 70mm footage is from the Apollo 14 launch, which DNEG cleaned up and then extended with extra plumes, which Lambert describes as a ‘cinematic’ enhancement. The process of cleaning up the footage actually almost made it too clean, and so it also had to be degraded somewhat to match the surrounding scenes.

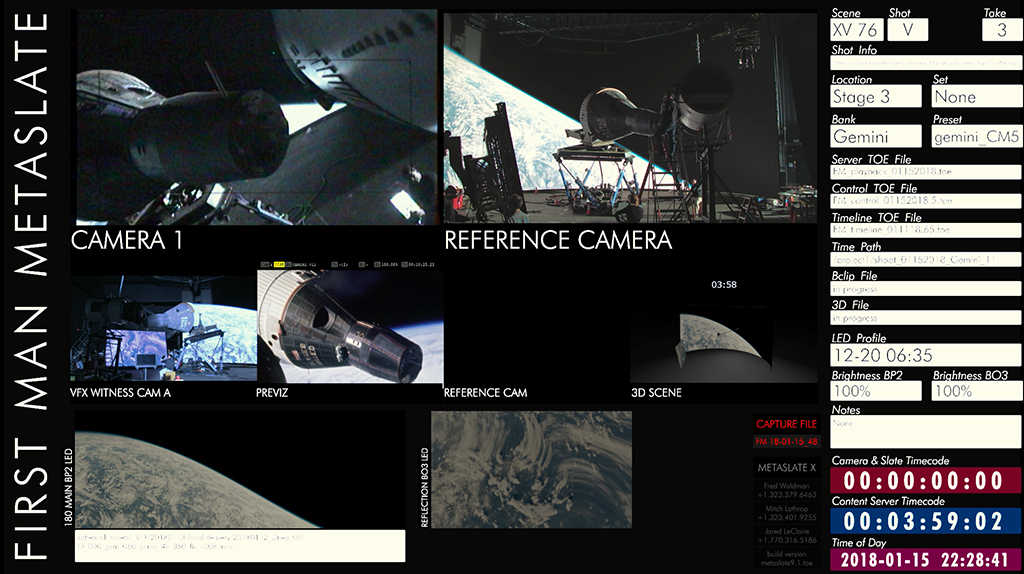

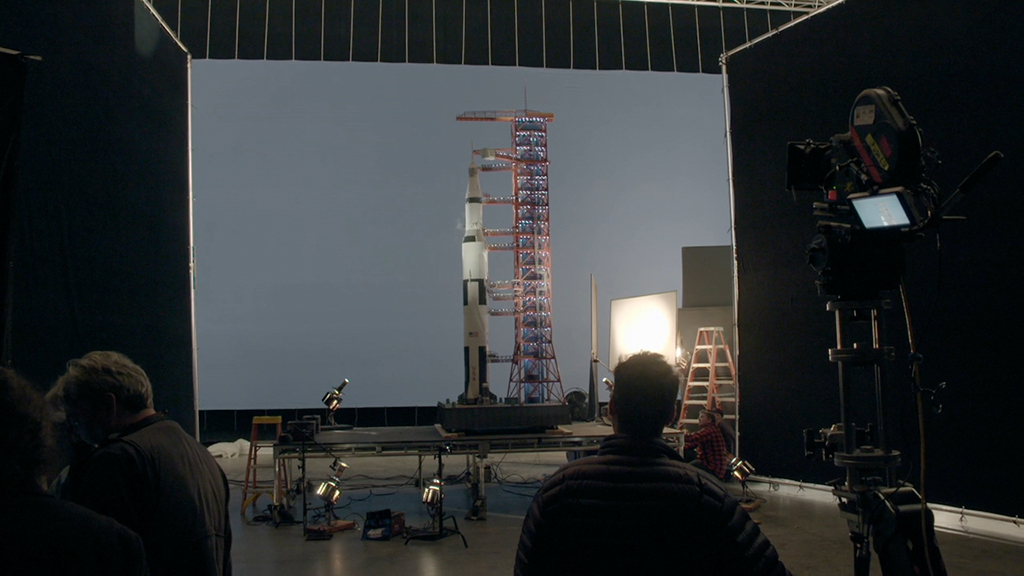

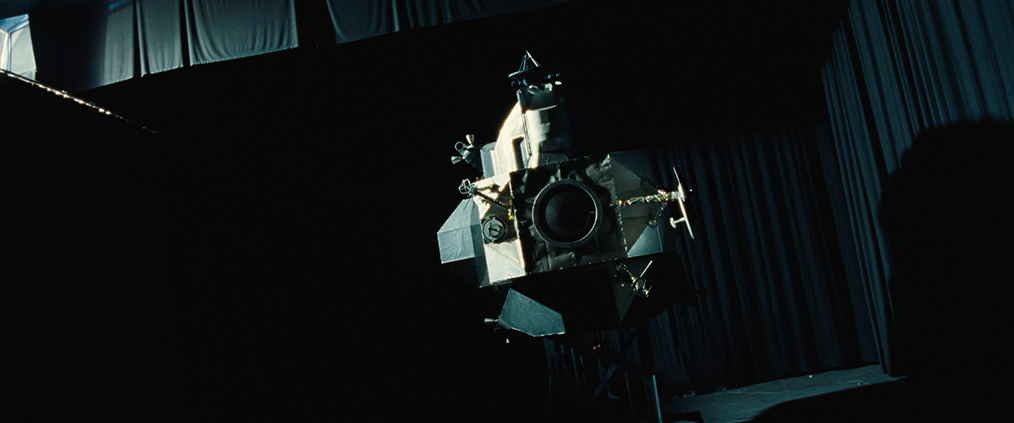

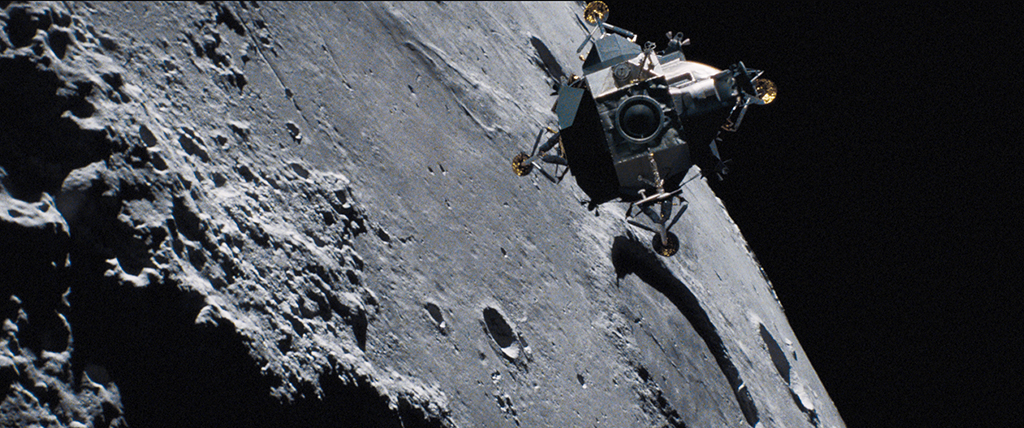

Miniature elements came into play for a few crucial space vehicles, fitting into the film in accordance with a pre-determined methodology, as Lambert outlines. “If there was a shot where you saw part of one of the crafts, we would either use full-scale or about 80% versions of the crafts we made as ‘full-sized’ props. And if it was a mid-shot, we would use Ian Hunter’s 1/6th-scale version of the miniatures. And if it was a wide shot, it was okay to be CG. Ian also made one 1/30th scale of Saturn V, which is in a couple of shots, and that beast was about 14 feet tall.”

“If there was a shot where you saw part of one of the crafts, we would either use full-scale or about 80% versions of the crafts we made as ‘full-sized’ props. And if it was a mid-shot, we would use Ian Hunter’s 1/6th-scale version of the miniatures. And if it was a wide, it was okay to be CG. Ian also made one 1/30th scale of Saturn V, which is in a couple of shots, and that beast was about 14 feet tall.”

—Paul Lambert, Visual Effects Supervisor, DNEG

Hunter’s team crafted the Saturn V from PVC piping, acrylic tubing, and from 3D-printed and laser-cut parts. The other miniatures, which included the Command/Service Module (CSM) and the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM) were constructed at 1/6th scale with 3D- printed and hand-sculpted materials. The models were captured on a shooting stage in Atlanta with DNEG composited miniature photography into various scenes, sometimes extending craft with CG elements, or augmenting craft with interactive light.

“The whole stage was covered in black,” details Hunter. “We had a three-axis model mover that mounted to each of the models, which was also covered in black. We had a single key light as the sun, which was off at the far end of the stage to give us nice coarse shadows. There’s no bluescreen or greenscreen – if we needed to do composites, we shot a separate overexposed pass of the ship, like a roto-matte guide that gave you a defined edge.”

While the blacked-out stage was the main approach to capturing the miniatures, the LED screen used for live action was also utilized to add interactive lighting. “We had a projector on stage,” says Hunter, “and we projected the Earth onto the CSM surface, so as it rotates into position to lock onto the Lunar Module, you could see that Earth reflection moving on it. It’s vague, but gave it that sense of texture, that authenticity that would’ve been lacking if we just shot it simply as a bluescreen element.”

“The miniatures on this movie,” adds Hunter, “required a lot of forethought and integration into the production pipeline for them to be carried out. I think that’s another commendable thing on the part of the production, to commit to such a bold move, to not just let it go into ‘greenscreen world’ and hope it works in the end, but to actually think ahead of time and make it integrated and part of the actual photography on the day.”

A greenscreen world was also something avoided for the moon landing itself. Here, Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s (Corey Stoll) eventual moon walk was captured – in IMAX – on a working quarry outside of Atlanta, where the ground was dressed with specific gravel that matched the lunar surface, and a full-sized LEM was also built. DNEG’s initial work on the sequence involved using relevant moon archival photography to represent the craters and surface, and to clean up the quarry backgrounds.

Another was to deal with visor reflections. “Every shot where you saw an astronaut had a view of the camera,” says Lambert, “and the IMAX camera is absolutely huge, but also you got to see all the crew as well, the tents and everything else. So part of the visual effects work was to re-create the scenes digitally, and then remove the camera and the crew – who all leave tracks and marks in the gravel. So that needed to be cleaned up, too. Plus, this is IMAX, so when you get your 8K scan back and you look at it, you can still see footsteps!”

To help with the feel of being present in 1/6th gravity, every time there was a footstep or a jump, DNEG added CG dust into the footsteps. The astronauts were attached to a bungee system calibrated by Stunt Coordinator James M. Churchman to also provide a level of anti-gravity, and this was also removed in post. In addition, DNEG worked on a few lighting and shadow fixes; Sandgren had employed an enormously bright 200K bulb to represent the sun, which provided a distinctive, harsh shadow. For a few scenes, only two 100K lights had to be used, which provided a different shadow, and VFX artists made the appropriate augmentations.

“[P]art of the visual effects work was to re-create the scenes digitally, and then remove the camera and the crew – who all leave tracks and marks in the gravel. So that needed to be cleaned up, too. Plus, this is IMAX, so when you get your 8K scan back and you look at it, you can still see footsteps!”

— Paul Lambert, Visual Effects Supervisor, DNEG

“One thing that did happen was that it was really cold in Atlanta, and I could feel my lips chapping,” says Lambert. “And I thought it was really cold until I saw myself in the mirror and I had rosy cheeks. I got sunburned from that damn bulb! It actually sunburned me. It was that bright. Talk about trying to do things practically…”

Indeed, practical on-set solutions were a large part of First Man. In addition to the motion-based rigs mounted by Schwalm, his team also delivered a Multi-Axis Trainer the astronauts use on the ground, and the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle, or LLTV. “They actually built a full-size replica of the LLTV,” explains Lambert. “It was hung from computerized cranes. The idea was that these cranes would provide all the rotation for the LLTV, but we shot it from the helicopter going in a circle around it, and also a Russian Arm that was going around in a circle on the ground.”

“When you saw the footage,” adds Lambert, “it really gave you the impression that you were getting translational movement on the LLTV when, in fact, it was always in the same place. The additional effects work we had to do there was to remove the cables which were attached to the LLTV, then also add an additional small puff of smoke coming from all of the stabilizers, and a wide shot which was all CG.”

By their very nature, sometimes visual effects considerations crop up after live-action scenes are filmed. But, according to Lambert, this was not the case on First Man. The time spent planning sequences, building miniatures and preparing the LED footage, for example, meant VFX considerations came early. And especially in relation to the LED playback, the filmmakers had something to directly adapt to on set, rather than imagining things on a greenscreen.

“Visual effects were very much a part of the filmmaking process,” declares Lambert. “It was a very collaborative affair in that, because I was actually providing moving content and was able to interact with the edit of that content on the set, we suddenly became a lot more involved, rather than what is usually the case in visual effects. You usually advise for some particular thing, and you capture as much data as possible, knowing that you’re going to have to do something later. And yes, we had hundreds of shots which we did in post as well, but we were also very much involved in the day to day shooting.”