By TREVOR HOGG

By TREVOR HOGG

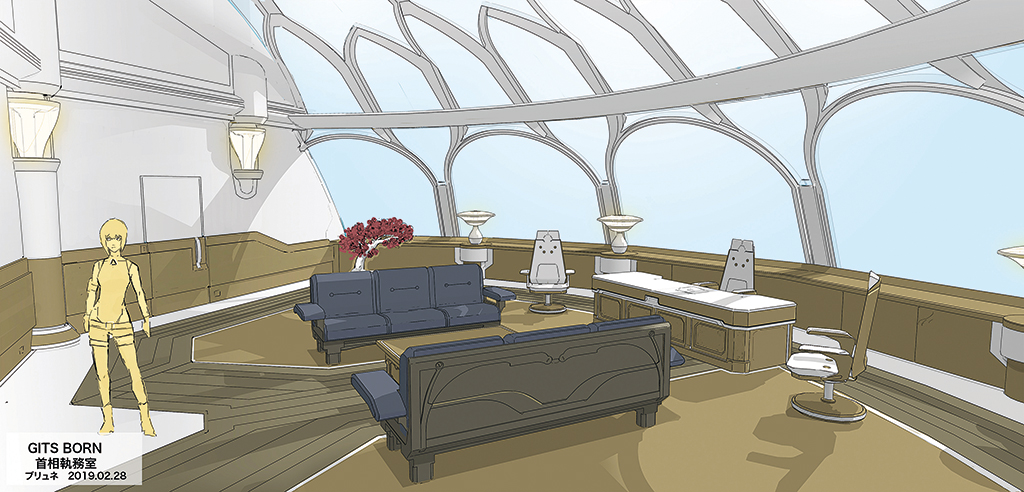

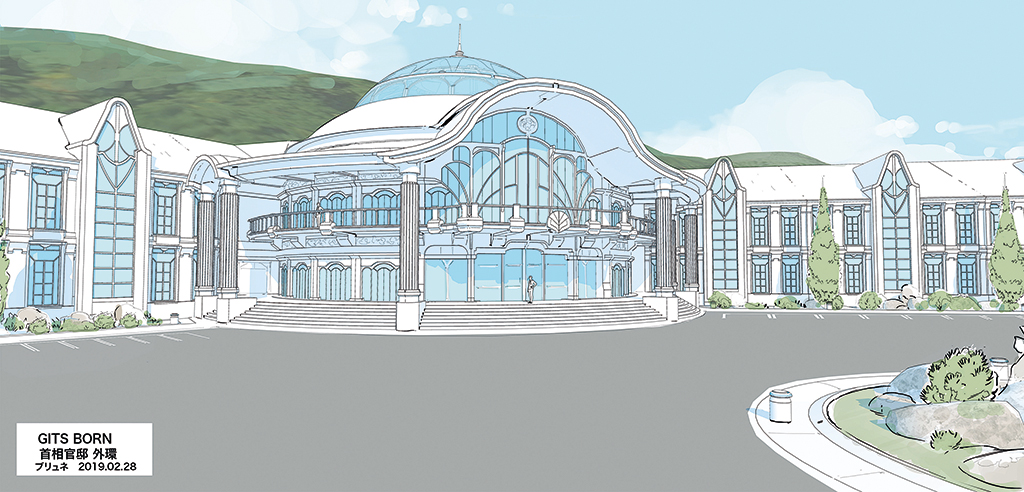

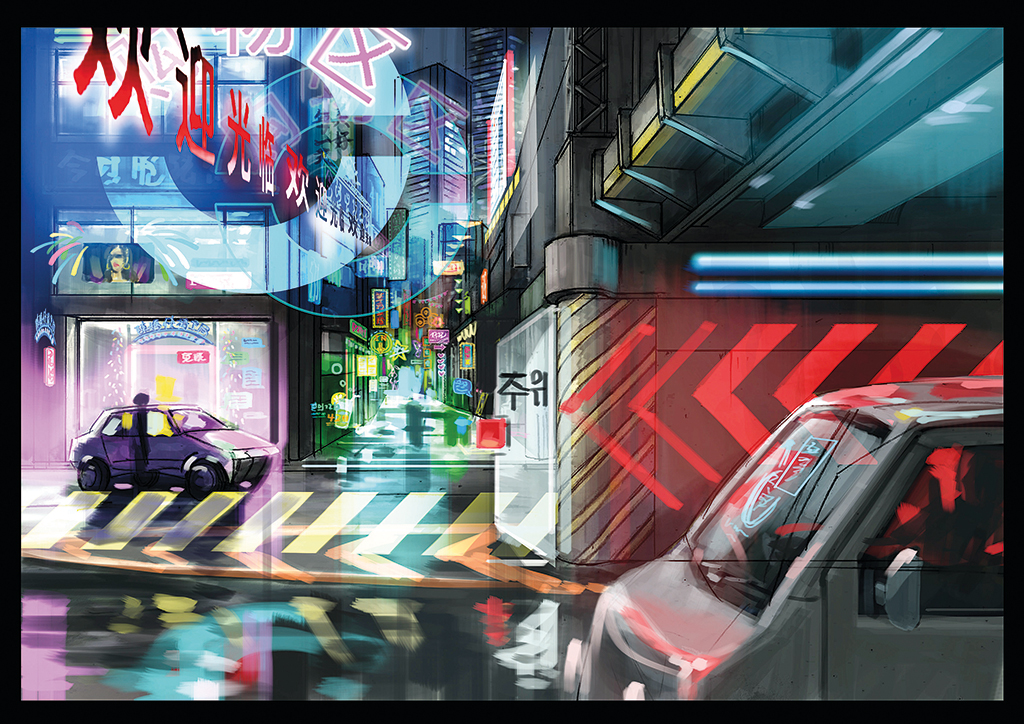

The Ghost in the Shell franchise, established by manga artist Shirow Masamune, revolves around a counter-cyberterrorist organization called Public Security Section 9 battling criminals and conspiracies in 21st century Japan where people have cybernetic implants to enhance their capabilities. As part of this franchise, Japanese anime director Kenji Kamiyama created the Stand Alone Complex television series in 2002, which ran for two seasons and spawned a feature film. The project has recently been revived, with Production I.G and Sola Digital Arts partnering with Netflix to produce Ghost in the Shell: SAC_2045, which will consist of two 12-episode seasons.

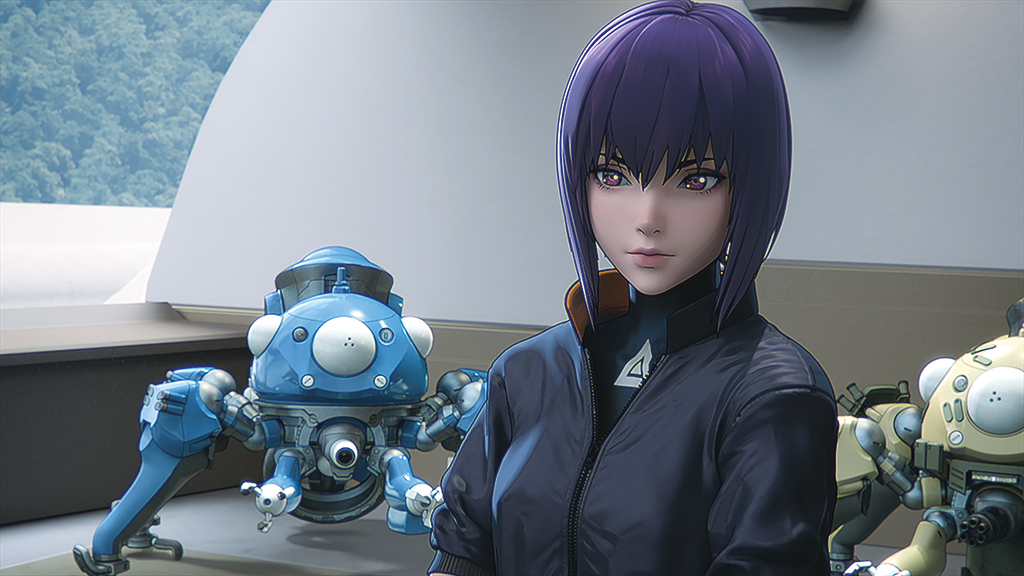

This time around, the disbanded members of Section 9, led by Major Motoko Kusanagi, are a mercenary group known as Ghost that reunites with their former Chief, Lt. Colonel Daisuke Aramaki, in an effort to contain the mysterious global threat of highly evolved beings referred to as ‘Post Humans.’

Kamiyama shares directorial duties with Shinji Aramaki (Appleseed), with the duo communicating as one by translated emails, courtesy of Netflix. “Every time Ghost in the Shell is adapted, each director and production team explores a different way to represent the series. This time, however, the concept of creating a series in full 3D CG itself was a completely different approach from the previous projects. While this project was based on the S.A.C. series directed by Kenji Kamiyama and its world, it tells a story that exists parallel to the previous stories in the franchise.

“After we shared our ideas on the project, director Kamiyama took on the series composition at the pre-production stage and would consult with director Aramaki at the episodic screenplay development stage. For the development of character and production design and all stages after storyboarding, we took on the same position, and would carry out checks and proceed together until each part was complete.”

Adopting a realistic approach for the animation was important for Kamiyama and Aramaki. “Conveying the drama of the story to the audience through animation was a top priority. To do so, we utilized motion capture and tried to have life-sized characters act as much as possible. Specifically, we avoided the unnaturally shaped bodies and faces that are common in full CG animation and opted for proportions similar to those of real humans. This is because we wanted to use a style that would allow the audience to concentrate more on the story.”

Russian illustrator Ilya Kuvshinov provides his own interpretation of the Stand Alone Complex characters that were originally designed by Hajime Shimomura. “We instructed Ilya that while Ghost in the Shell is sci-fi, we weren’t looking for out-there clothing designs and asked him to keep within the confines of clothes that actually exist or look like they would exist. Also, after thoroughly explaining one by one the images we had in mind for the characters, we held one-hour meetings every week to check the designs. All the character designs for the entire series eventually came together after more than a year of doing this.”

“Priority was given to making things seem like they could exist in the real world over giving them futuristic designs. That’s because we thought full CG would work better with realistic designs. The armored vehicles and the vehicles that the members of Section 9 ride in Los Angeles are based on actual military ones. In contrast, the drone that appears in Episode 2 is a private drone that’s been loaded with Hellfire missiles, so actual civilian drones were referenced for the design.”

—Kenji Kamiyama and Shinji Aramaki, Co-directors

“Conveying the drama of the story to the audience through animation was a top priority. To do so, we utilized motion capture and tried to have life-sized characters act as much as possible. Specifically, we avoided the unnaturally shaped bodies and faces that are common in full CG animation and opted for proportions similar to those of real humans. This is because we wanted to use a style that would allow the audience to concentrate more on the story.”

—Kenji Kamiyama and Shinji Aramaki, Co-directors

Combining motion capture and computer animation was a familiar approach for Aramaki. “Aramaki was originally one of the first people in Japan to do a motion capture-based anime. He has been using motion capture for performances in animation since the release of his movie Appleseed in 2004. However, around the world, those who use motion capture in this way are in the minority, with the majority of CG production teams still considering the motion capture technique as just a tool for creating ‘action scenes.’ While Aramaki advocated that ‘it’s theatrical performances, in particular, that should use motion capture,’ he found little support in the industry. The reason why Aramaki thought Kamiyama would go for motion capture was that his works contained live-action-esque performances and stories that are developed via the script.

“It’s established that the members of Public Security Section 9 are a polished and professional special unit, so they don’t perform any character-specific actions,” note Kamiyama and Aramaki. “That’s because such professionals all go through the same theory-based, high-level training, so their actions and styles should resemble each other. For the members of Section 9, we aimed for them to perform reasonably streamlined and modest actions. Alternatively, by giving the actions of the enemies [for example, Post Human] unique characteristics, we were able to contrast them with the actions of the Section 9 members and make them look that much better.”

A dramatic showdown occurs in Episode 5 on the estate of tech billionaire Patrick Huge that features robotic guard dogs, cyborg housemaids and an armored suit. “For these scenes, we had action coordinator Motoki Kawana devise special action sequences at the motion capture stage. Then for the subsequent animation process, we had our most skilled special animator on the production team take charge. By combining the skills and ideas of both an actor in charge of the action and a special animator, we were able to create some great fight scenes.

“The use of motion capture allowed for an environment that made it easier than conventional animation production to create blank space durations, so storyboards were often off the mark in regards to the fixed episode length,” state Kamiyama and Aramaki. “Even after reaching the post-motion capture animatics [layout] stage, the average length of an episode was three to four minutes over the fixed episode length. After that, we would cut out any unneeded parts and picture lock the episode before moving onto hand animation. The longest cut we had to make from an episode was eight minutes long.”

Action takes place in the economically devastated cities of Palm Springs, California and Los Angeles. “For Palm Springs, we actually went there. In the Japanese scenes, as Fukuoka is the capital city [in the series], location designs were based on the actual city of Fukuoka. Since Aramaki happens to be from Fukuoka, he was able to realistically recreate downtown Fukuoka [Hakata] without visiting. For example, the area around the bank that appears in Episode 7 was recreated so faithfully that someone from Fukuoka would easily be able to tell where it’s modeled after.”

“Such scale and quantity of resources were impossible with productions in Japan up to this point. Even when we did it in 2D, we were told that making a Ghost in the Shell series was a ‘reckless endeavor’ because of the number of assets and locations that need to be produced. The story is dense, and there’s a huge amount of information packed in the visuals, so we think you’ll probably wear yourself out if you binge-watch it!”

—Kenji Kamiyama and Shinji Aramaki, Co-directors

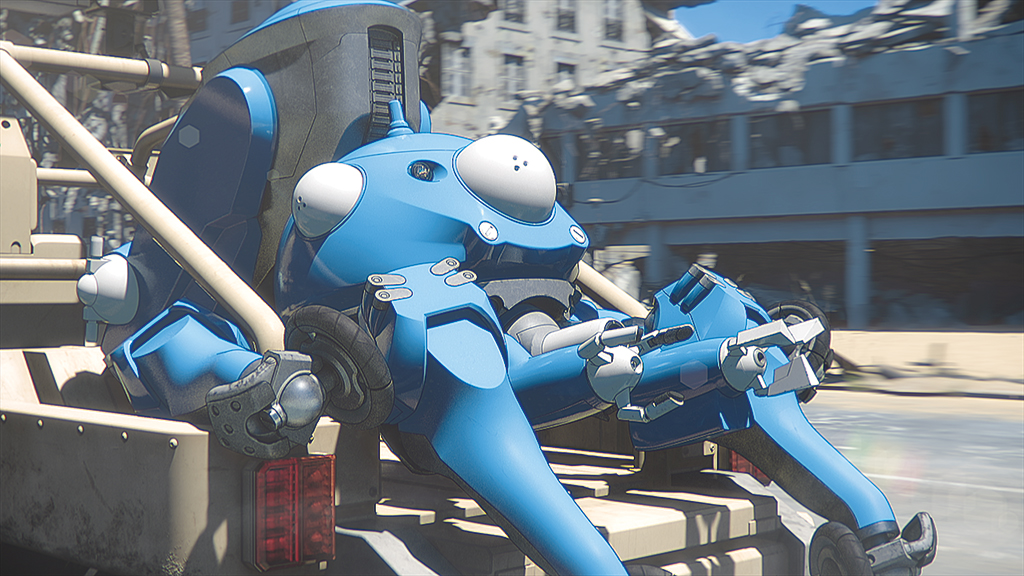

Among the high-tech weaponry are artificial intelligence ‘think tanks’ and attack helicopters. “Priority was given to making things seem like they could exist in the real world over giving them futuristic designs,” remark Kamiyama and Aramaki. “That’s because we thought full CG would work better with realistic designs. The armored vehicles and the vehicles that the members of Section 9 ride in Los Angeles are based on actual military ones. In contrast, the drone that appears in Episode 2 is a private drone that’s been loaded with Hellfire missiles, so actual civilian drones were referenced for the design.”

Signature elements include the ability to hack into a human mind and thermo-optical camouflage. “The way we showed brain dives and thermo-optical camouflage followed all the Ghost in the Shell series up to this point. That being said, with regard to thermo-optical camouflage, we were able to take advantage of full 3D and succeeded in producing a sense of transparency while maintaining a three-dimensional feel. This was something that was attempted for the 2D series as well, but it was difficult to achieve such a look with drawings.”

The major task for Kamiyama and Aramaki was producing an anime series of 22 minutes per episode that included backgrounds using only 3D CG. “Such scale and quantity of resources were impossible with productions in Japan up to this point. Even when we did it in 2D, we were told that making a Ghost in the Shell series was a ‘reckless endeavor’ because of the number of assets and locations that need to be produced. The story is dense, and there’s a huge amount of information packed in the visuals, so we think you’ll probably wear yourself out if you binge-watch it! But we also hope that everyone is able to enjoy those aspects too.”

Illustrator Ilya Kuvshinov is based in Tokyo, Japan, and describes Ghost in the Shell: SAC_2045 as “the most awesome project” he has ever worked on. “On the design meetings we talk about the ‘feel’ a character should invoke in a viewer, and basic movie-watching experience is really helping a lot here because it’s a usual point of reference.”

Visual research went beyond the Internet. “For example, when I designed a character in kimono, I bought a book called Kimono Guide for Novices that thoroughly explained how to put it on, which materials are used, and design flow. When designing military costumes, I bought a book just for those. I own a lot of books now!” When designing the characters for the Netflix series their physical and cyber abilities needed to be kept in mind. “That’s actually a big thing, because the cyborg-to-human-body ratio really affects the weight of some parts of your body in different movement and postures. Basically, you need more sturdy pants for just sitting around or stronger shoes just to stand. That’s why Motoko has heavy boots in real life but high heels in virtual space.”

No alterations were required for the iconic Batou, while Togusa was given a “hard-boiled” look for the sake of the story. “Motoko’s design logic was the most fun one,” notes Kuvshinov. “She’s a full-body cyborg, so she can actually own any body she wants. This time, I thought about what kind of body does she like for the fast, agile movements.” Getting the proper hairstyle was important for Daisuke Aramaki. “When I did the first sketches for Aramaki, director Kamiyama asked me to make his hair point up, for a more energetic feeling. That edit was so simple but so powerful in terms of how you see the character subconsciously, just basing your feelings in shapes.”

Founded by Shinji Aramaki, producer Joseph Chou and CG producer Shigehito Kawada, Sola Digital Arts provide insights into bringing the cyberpunk action tale conceived by Shirow Masamune into the realm of 3D CG for the first time.

“Compared to our previous project, Ultraman, Ghost in the Shell: SAC_2045 is more realistic,” remarks Modeling Supervisor Masamitsu Tasaki and 3D Character Supervisor Hiromi Matsushige. “Even so, since it is still an anime, characters were lined with Pencil [a rendering plug-in that outputs cartoon-like outlines]. Also, we took certain measures when we wanted to give it a little more of that anime feel, like reducing the size of feet of Motoko.”

All of the 3D animation was done in Maya. “Basically, character designs came together after discussions between the two directors and Ilya Kuvshinov,” explain Tasaki and Matsushige. “Based on those, we would work together with the directors to add the final touches. Both directors requested that models be closer to real-life than the unrealistic bodies commonly found in cel animation, so we worked on creating character models in response to requests such as ‘don’t make the legs too long.’

“At the beginning of the project, there weren’t enough solid design drawings, so we went through Ilya’s past illustrations. It was difficult to convert Ilya’s designs into 3D, and we got quite confused along the way, but in the end we managed to pull through and bring them together. Ilya’s style of coloring is quite unique, so we focused on how to add specular reflections. We also paid close attention to getting the texture of the hair right.”

Models assets were created by different animation studios. “To do this, the main staff first created the textures and base models for the male and female characters, then assets would be derived from them,” remark Tasaki and Matsushige. “This allowed us to maintain some kind of consistency.”

Motion capture improved the performance fidelity of the animation. “By using motion capture, we were able to incorporate not only the sensibilities of the animators, but also the consistent performances and emotions of the mocap actors too,” states Chief Episode Director Hiroshi Yagishita. “For this project, auditions narrowed down over 200 people to just six mocap actors who became the fixed cast for the entire series. [Through the use of mocap actors] we were able to express natural human-like movements in not only the main characters, but the supporting characters, too, while adding depth to the world of the series.”

Storyboards were designed around the fixed episode length of around 22 minutes. “In the subsequent animatics [layout] stage, it was often the case that episodes came to be around 26 minutes long because there was more captured in the motion capture than was expected,” remarks Yagishita. “After that, the animation would be cut down to fit the fixed length. The workflow of this project avoided adhering too strictly to the details of the storyboards and animatics. Instead, we took advantage of the performance of the mocap actors to review, and create camerawork and cuts during the layout process.

“At the character design stage, we were aware that costumes and character styles needed to allow for action. In terms of action sequences, live-action animatics (video storyboards) of the mocap actors were shot in advance. We would then examine the actions and continuity.” Body shapes and cyber abilities were taken into account with the character designs. “While acting out scenes, various expressions – such as lip movements which wouldn’t usually be necessary for wireless cyber communications – were used based on the specific situation and emotions of the characters.”

Military training was given to the mocap actors, such as how to handle guns and operate as a platoon. “We had a dedicated stunt actor perform the action scenes, and we would decide upon actions and fight styles that matched a character’s personality after consulting with the directors,” remarks Lead Animation Artist Yuya Yamaguchi. “The animators would also use this as a reference. Animators would use the actor’s performances and storyboards to create Motoko’s stylish movements, while for Batou, his powerful and swinging movements were beefed up during animation.”

The main protagonist, Major Motoko Kusanagi, took the longest to develop. “More attention was paid to the finer details, such as her eyelashes and the lines of her eyes, than to the different parts of her body. Since Ilya’s eyes are so distinctive, I created a collage of his illustrations of Motoko Kusanagi, which I used as a reference when making it possible to reproduce them. Also, since Ilya’s illustrations are cute we wanted to make Motoko cute. I think her design came out a little different from the Motoko we’ve seen until now and will be well received by newer anime fans alike.”

Providing military support and a childish eagerness are the Tachikoma think tanks. “The challenge that took the longest to overcome was probably making it possible for characters to fit inside its pod,” reveals background and vehicles modeling artist Vlastimil Pochop. “Since there was only a single unified size for all the Tachikomas, it wasn’t easy to figure out how the interior would fit such a broad spectrum of characters of various sizes while keeping the exterior in line with the concept art. All that while also thinking about the rig and animations. It was necessary to make my own simple rig and animations that I later shared with the riggers as reference. That way I could make sure all those geometry layers sliding over each other won’t clip through as the pod opens up. The low-poly stage of the development involved a lot of consulting between me, the concept artist, the riggers and the directors.

“As for the high-definition model, I had to be careful not to deviate too much from the concept art by adding too much detail. The new version of Tachikomas is different from the original, yet they share some similarities, like their fairly simple spider-like shape and their color palette. Adding too much geometric details or weathering would deviate from the concept.”

Robodogs are lethal and relentless. “This is a simple asset, but the challenge here was to make it transform into its shape from a box,” observes Pochop. “The first thing I did is to make a very low-poly version with a rig, and transformed it using bones and a little bit of blend shapes to see how close I can get to the concept while having the ability to transform. This asset also involved quite a lot of back and forth between me and the rigger. After that, the asset was passed to another modeler for HD pass.”

The threat level escalates when Motoko and her mercenary colleagues have to battle an adversary wearing an armored suit. “With its quite unusual silhouette it was a little bit challenging to get the upper and lower body balanced in just the right way. And again, with a pretty tall character to visibly fit inside, it took a while to match the interior and exterior.

“Because the concept design didn’t have quite enough detail in it, I also had to add some extra details while making sure these details didn’t result in undesirable outlines and overall look. This applied to all the other assets as well. While modeling, I needed to keep thinking in the back of my head how it would eventually look with outlines included. That’s why I would sometimes rather use textures and normal maps to add details instead of actual geometry. This asset also had a couple of damage states, but these weren’t particularly difficult to make. The only challenge here was to resist going too crazy with these bullet holes.”

During compositing, the color of the background and the shadows of the characters were matched first. “As it’s an anime, there was no need to rigorously match the shadows like photorealistic works, so there are times when we let characters stand out,” explains Lighting, Composite Supervisor Kouya Takahashi. “Also, since there are so many scenes in the series, the methods change slightly for each one.” The thermo-optical camouflage had to be readable and invisible at the same time. “At first, we made something similar to a pre-set, but it needed to be adjusted for each shot. As the distortion of the cloaks makes them easier to see, the areas behind the characters change their impression considerably. It was necessary to choose the level of visibility of the cloaks for each shot based on whether or not the actions of the characters needed to been seen, so I don’t think there ever was a right balance to be found.”

“This had the largest number of assets of any project we’ve worked on,” state Tasaki and Matsushige. “Looking back, the battles were cool. The scenes in Episodes 1 and 2 where the Tachikoma go up against tanks looked really good in 3D CG. Also, the entire series was made with an emphasis on story, so I hope everyone enjoys that element too.” Tasaki concludes, “Although the series does have a new look, people will enjoy Ghost in the Shell SAC_2045 when they watch it as one complete package.”