By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Stan Winston Studio Archives.

By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Stan Winston Studio Archives.

Stan Winston poses with the Chip Hazard and Archer puppets created by SWS for Joe Dante’s Small Soldiers.

Like many before and after him, Stan Winston wanted to become a movie star, and the ambition became a reality indirectly as he infused personalities into his creature effects, resulting in four Oscars, three BAFTA Awards, two Primetime Emmy Awards and being honored as an inaugural inductee of the Visual Effects Society Hall of Fame in 2017.

As a teenager growing up in Arlington, Virginia, he would transform himself into a werewolf by using rudimentary makeup and scare the neighbourhood children. “He loved the classic Universal monsters, Lon Chaney and Jack Pierce,” recalls Matt Winston, son of Stan Winston. “The Wizard of Oz was his favorite movie.” After his first year of studying dentistry at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, the undergraduate decided to major in Fine Arts and minor in Drama. “Dad was in the Virginia Players at the University of Virginia, and not only did he act but was essentially the makeup department. Through his Fine Arts major, he was learning all of the fundamentals, like perspective, highlights and shadows.”

Upon arriving in Los Angeles, Stan Winston couldn’t find any jobs as an actor and had an epiphany when watching Planet of the Apes. “He thought, ‘Maybe my other passion of makeup effects could be my way into Hollywood until I have my big break as an actor,’” Matt Winston remarks. “Dad found out about the Walt Disney Studios makeup apprenticeship program under Robert J. (Bob) Schiffer. This was the other foundational experience of his artistic career. He worked on Disney specials and some of those great Disney films from the late 1960s with Kurt Russell. Then he founded Stan Winston Studio in 1972 at the age of 26. Stan Winston Studio was the garage and kitchen table of our tiny two-bedroom house in Encino, California!”

An early career breakthrough for Stan was the television movie Gargoyles. “He came on to handle background gargoyles, which were pullover slips latex masks,” Matt Winston states. “In the early part of the shoot he was told by the producers that there was going to be no credit for him and the makeup leads Del Armstrong and Ellis Burman, Jr. He said, ‘This show is called Gargoyles, and since we’re essentially creating the stars of the movie for you, unless we get proper credit, I’m walking off this project.’ The producers acquiesced and gave them all credit, and because of that they all won Emmys.” Another area of significant impact was worker benefits. “Dad was instrumental in getting his on-set crew designated as puppeteers, which meant their work fell under the umbrella of Screen Actors Guild, allowing them to qualify for SAG residuals and health benefits; he could be tough but his crew knew that he had their back. The fact that Dad kept a core team for so many years speaks highly of the company culture of Stan Winston Studio and the man who led it.”

For two and a half years Alec Gillis was part of Stan Winston Studio before departing to form Amalgamated Dynamics, Inc. with co-worker Tom Woodruff, Jr. “I did not learn techniques from Stan but a creative philosophy,” Gillis notes. “His approach to running a business and being a creative artist was most like my personality. Stan was a father figure and mentor to a lot of people. He was not an easy-going guy because he was pushing hard to get the best quality and was committed to the journey and craft. Stan would toss you into the deep end, and I was grateful for the opportunities that he gave me. Stan wasn’t a niche character creator. He would take on anything from a rubber W.C. Fields nose to a 40-foot-tall Queen Alien. It’s all character. I’ve always respected that because I got into the industry to do interesting things, not to pursue a single technique.”

Stan Winston sculpts a bust of his friend and frequent collaborator, Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Stan Winston with Danny DeVito during a Penguin makeup test at Stan Winston Studio for Batman Returns.

Aliens writer/director James Cameron and Stan Winston review the progress of the clay Alien Queen design maquette at Stan Winston Studio.

Stan Winston applies his Emmy-winning old age makeup to Cicely Tyson for The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman.

Winston never forgot about what he learned from his acting classes. “There was a time on Aliens where he had a metronome going so there was a frame of reference for the puppeteers to lock their brains around for their performance,” Gillis states.

Stan Winston and the SWS crew prep the full-size animatronic T. Rex for action on the set of Jurassic Park.

Johnny Depp transforms into Edward Scissorhands during a test makeup application and scissorhands fitting at Stan Winston Studio.

“Stan was looking for organic ways to make these rubber, metal and plastic creations come to life, and he saw it as performance rather than as robotics. When you were puppeteering for him, he wanted you to be in the state of mind of an actor even though you’re only creating the movements for one portion of this character. You had to also think of it as an orchestra that comes together to create an emotion. He would talk in those terms rather than get bogged down with servomotors. Stan showed me that most successful performance characters are done by people who are artists and performers, and the support people are the engineers.”

“People magazine did an article about special effects makeup, and Stan’s quote was, ‘Some of my best work has been in some of the worst movies,’” remarks Tom Woodruff, Jr. “I remember reading that and thinking it’s interesting because what’s he’s basically saying is, ‘I love to work and love what I do.’ He didn’t care if it was a big or small movie that would never perform because it gave him an opportunity to express himself as an artist.” Overtime was avoided as much as possible, as Stan Winston wanted his team to be mentally fresh and wanting to work the next day. “It was a big find that Stan was such a family man and realized that there had to be a balance.”

Stan Winston adjusts one of the full-size animatronic T-800 endoskeletons on the set of Terminator 2: Judgment Day.

Stan Winston gives feedback on the progress of creating Archer’s head for Small Soldiers.

Kevin Peter Hall and Stan Winston take a break at the makeup effects trailer on the set of Predator while SWS artist Matt Rose works on the Predator bio-helmet in the background.

Stan Winston, Producer Richard Weinman and the SWS crew on the set of Winston’s directorial debut Pumpkinhead. From left to right: Alec Gillis, Stan Winston, Tom Woodruff, Jr. (in Pumpkinhead suit), Richard Weinman, John Rosengrant and Richard Landon.

The Monster Squad was a great experience. “Stan was in the drawing room doing sketches of a new creature from the Black Lagoon, but not from the Black Lagoon because that was licensed,” Woodruff, Jr. states. “I was watching him, and he was showing me all of this fine pencilwork where you go in with more pencilwork to make things shaded, and it had great volume to it. I still draw that way.” A fond memory of Woodruff, Jr.’s was Winston painting some appliances for The Monster Squad with him. “Stan came in, and we were talking. I asked him, ‘Do you mind helping me paint one of these?’ I just wanted to paint with Stan Winston. He said, ‘Mind? I would love to.’ We sat there painting Frankenstein appliances for a couple of hours; that was always such a big thing for me to be able to have that time with him.”

Considered to be Stan Winston’s right hand was John Rosengrant, who went on to establish Legacy Effects with colleagues Lindsay MacGowan, Shane Mahan and Alan Scott after their mentor’s death in 2008. “My 25 years with Stan helped to propel me in this business, and I learned so much from him,” Rosengrant notes. “Being his right hand became easy because it felt right. He ran Stan Winston Studio as a true business. There was a time in and out. We had a lunch hour. And his philosophy wasn’t that we were the be all and end all. We are one important part of the filmmaking process. Stan would say, ‘What we’re doing is creating characters.’ We did create some iconic characters, and at Legacy Effects we continued doing that. When you think about it, the movie is called Aliens or The Terminator or Predator or Iron Man, and we are creating that character. The Queen Alien in Aliens is totally a character as is the T. Rex or the raptors in Jurassic Park or Edward Scissorhands – they are all etched in our brain.”

“I would say that The Terminator put Stan on the map for animatronics, and it’s an extension of puppeteering,” Rosengrant observes.

Stan Winston paints the full-size animatronic and rod-puppeteered T-800 endoskeleton for The Terminator.

“When Stan saw what they were doing with The Dark Crystal, he wanted to expand upon that idea and to take it into a more expansive role because you can do things with a puppet or animatronic that you can’t do with makeup. How are you going to do the Queen Alien unless it’s a giant animatronic puppet? The other thing is that Stan was willing to embrace digital. You could try to compete with it, but why? We’re all trying to do the same thing. Stan and I are of the mindset that whatever is the best way to get the shot is the way it should be. Stan opened Digital Domain [with James Cameron and Scott Ross] after our Jurassic Park experience because he saw the value in it. What it did for us with our puppeteering was suddenly some complicated mechanism to make an arm move could be simplified down to a rod because they could paint that out. It was always figuring out how to evolve and stay with the times, not get caught in the past.”

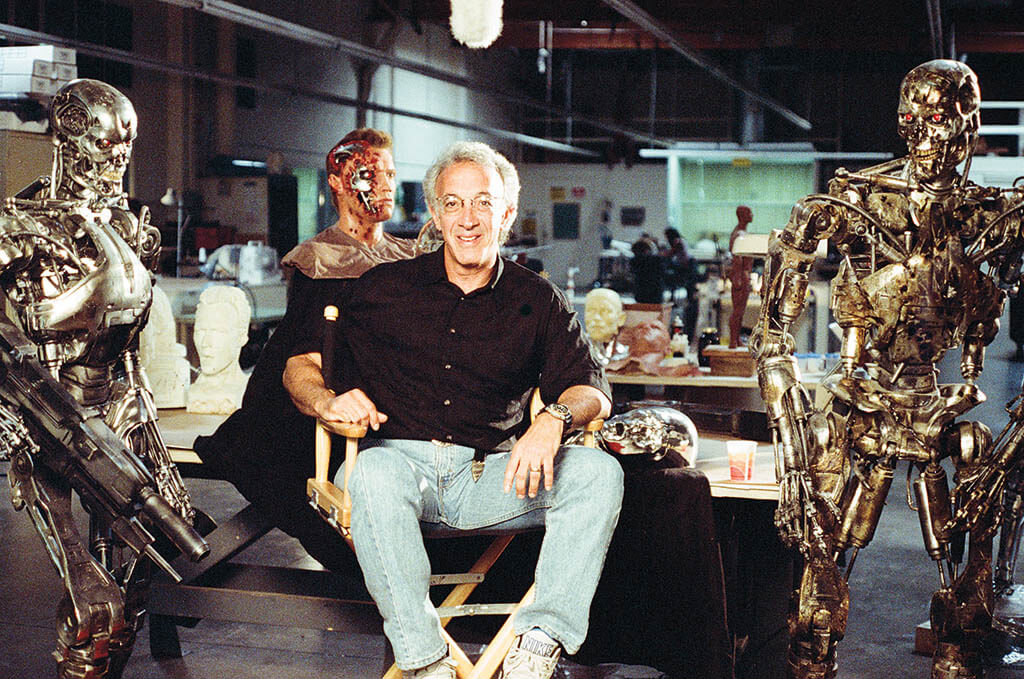

Stan Winston surrounded by just a small portion of Stan Winston Studio’s groundbreaking puppets and practical effects created for Terminator 2: Judgment Day.

SWS artist Alec Gillis sculpts the head of Pumpkinhead at Stan Winston Studio.

SWS artist and Pumpkinhead suit performer Tom Woodruff, Jr. paints the head of the newborn Pumpkinhead.

Stan Winston puts the full-size animatronic T. Rex through its paces on the set of Jurassic Park.

Stan Winston, SWS mechanic Al Sousa and SWS Art Department Supervisor John Rosengrant rehearse the movements of a Chip Hazard rod puppet for Small Soldiers.

Stan Winston, Kevin Peter Hall (in Predator suit) and the SWS Predator crew on location in Palenque, Mexico. From left to right: Shane Mahan, Steve Wang, Stan Winston (kneeling), Brian Simpson, Kevin Peter Hall, Shannon Shea, Richard Landon and Matt Rose.

James Cameron was not familiar with Stan Winston until special effects makeup artist Rob Bottin recommended him for The Terminator. “Stan wanted to empower his art team because that’s what they sell in addition to the technique and physicality of making moulds and doing puppeteering,” Cameron states. “I was a unique customer for him because I was coming in with my own drawings. I expected there to be tension around that and there never was. Stan celebrated art and design first and foremost, and he was excited by that. Stan put his designers on cleaning up, sculpting and getting on with the designs that I brought in, and where there were designs missing his guys went crazy. We meshed because we were all artists. We respected each other and the creative process. If I had one thing to say about Stan it would be that he always celebrated artists and the moment of creation whether that was a pencil sketch or a sculpture.”

A personal regret lingers from the making of Avatar. “We had an internal design team that was working closely with Stan’s team,” Cameron states. “After three and a half years into a four-and-a- half-year project, we finally had a short sequence of five or six shots of Neytiri, and she had basically come to life. You just see Neytiri’s eyes in the forest. She hops up on a branch, goes to shoot Jake and stops herself because this little Tinkerbell thing lands on her arrow. Those were the first shots completed by Weta Digital [now Wētā FX]. I knew that Stan was sick, so when I got those shots, I called him up and said, ‘Stan, you’ve got to see this. We’ve cracked the code.’ That turned out to be the last time I talked to him because when I went over the next day Matt Winston said, ‘He’s not having such a good day.’ I came back the following day and the housekeeper told me that he had passed away during the night. Stan never got to see the culmination of the dream that he and I set out to do when we founded Digital Domain.”

Sixteen years after his death, the impact of Stan Winston still resonates in the movie industry, with Legacy Effects carrying on special effects wizardry of Stan Winston Studio and the Winston family embarking on an academic endeavor. “Before Dad passed away [in 2008], he dreamed of stepping away from the day-to- day of the business, traveling the world and sharing how he and his team did it all,” explains Matt. “That’s how the idea of the school was born. We started working earnestly on the Stan Winston School of Character Arts in 2010, and that’s been the focus of the family ever since. It’s online educational videos by the leaders in the industry.” The global shutdown caused by COVID-19 had a major impact. “We were perfectly positioned for a pandemic, which accelerated the adoption and acceptance of online education by a decade.”

Reflecting on the influence of his frequent collaborator and business partner, Cameron states, “We were aligned philosophically on how important it was to have details and nuance. Stan thought like a director, and I thought like a makeup or visual effects guy. He and I met in the middle. His legacy is that every CG character that you see now, he was at the cutting edge of proving that technology.” Rosengrant has a fond memory working on Amazing Stories. “Stan took me aside and said to me, ‘You’re a really good artist.’ There are a lot of people who have some artistic gifts and need a place to develop them, and Stan had that atmosphere that allowed me to grow and develop. By him recognizing that, I felt like I had finally arrived at that point in time, and then it kept going up.”