By OLIVER WEBB

Images courtesy of Republic Pictures and Theodor Groeneboom.

By OLIVER WEBB

Images courtesy of Republic Pictures and Theodor Groeneboom.

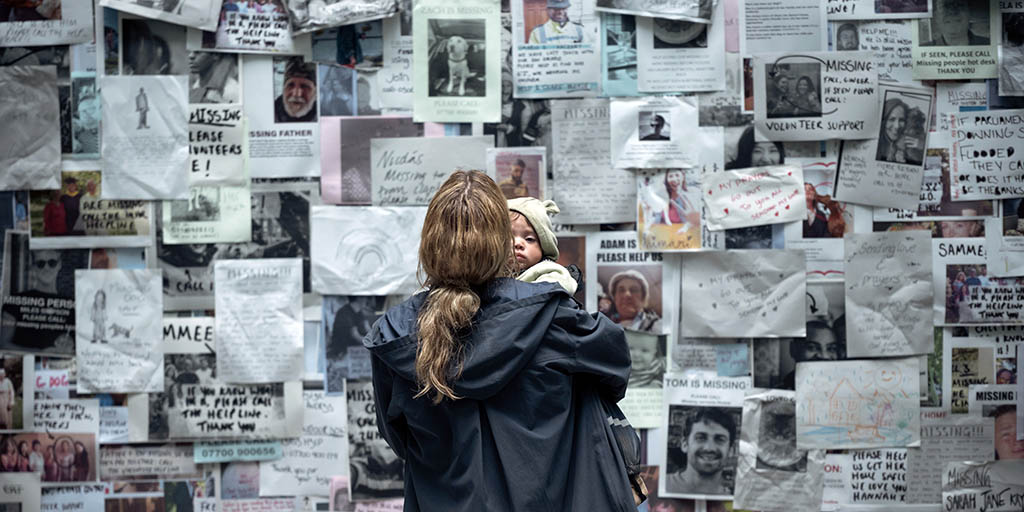

The woman (Jodie Comer} and her baby navigate the flooded streets of London with the help of greenscreen. Comer’s compelling performance was one of the anchors of the film.

Mahalia Belo’s remarkable feature directorial debut The End We Start From follows a woman (Jodie Comer) and her newborn child as she embarks on a treacherous journey to find safe refuge after a devastating flood. Based on Megan Hunter’s 2017 novel, The End We Start From is a hauntingly realistic depiction of a dystopian London submerged underwater.

Theodor Groeneboom served as Visual Effects Supervisor on the film. “A friend of mine in London went to film school with Mahalia,” Groeneboom recounts. “Mahalia reached out to me because of him. I used to live in London and worked in a few of the big studios there doing visual effects. Then, I moved back out to Norway a couple of years ago and started my own little company. We do quite a bit of work for the U.K. visual effects companies and some of the independent UK films as well. It felt like an extension of keeping in touch with everything that was happening there. I was involved from the early stages – the screenplay breakdowns, planning on the shoot and throughout the shoot and post-production, so it has been a long journey. I very much enjoyed it.”

Jodie Comer and Joel Fry in British survival drama The End We Start From.

The post-apocalyptic elements in the film are a backdrop in the story. “It’s not a visual effects film,” Groeneboom acknowledges. “That’s very much true for how the book portrays it as well. Production Designer Laura Ellis Cricks and Mahalia were very much into making sure the film has some kind of texture to it, not just visually but the way the landscape conveys through the film that it’s not just front and center that everything is happening.”

“We need to treat visual effects like some kind of story-driven element. They are just sprinkled around to provide texture to what is happening to Jodie [Comer] and her character, which is quite different from making a big scene and point out of it. It just happens to be what they are going through. There are quite a few scenes where we just put stuff in the background that could tell some kind of environmental thing that something has happened and not draw any attention to it. I guess that’s part of the whole textural side of things; they just want to paint the world but not make it completely obvious. I suppose subdued and textual were words that were frequently used about how to make the visual effects integrate.”

—Theodor Groeneboom, Visual Effects Supervisor

A woman (Jodie Comer) and her newborn child embark on a treacherous journey to find safe refuge after a devastating flood.

Explains Groeneboom, “It’s not so much a coherent film that goes from A to B; it sort of drifts in and out of these moments that you take in when you view the film that go away from the whole. We need to treat visual effects like some kind of story-driven element. They are just sprinkled around to provide texture to what is happening to Jodie and her character, which is quite different from making a big scene and point out of it. It just happens to be what they are going through. There are quite a few scenes where we just put stuff in the background that could tell some kind of environmental thing that something has happened and not draw any attention to it. I guess that’s part of the whole textural side of things; they just want to paint the world but not make it completely obvious. I suppose subdued and textual were words that were frequently used about how to make the visual effects integrate. Suzie Lavelle, the DP, was also a big part of that conversation in driving the lighting and the look of everything.”

The End We Start From is a hauntingly realistic depiction of a dystopian London submerged underwater.

Groeneboom and his team collected lots of material for visual references and relied heavily on the production design ‘bible’ that Production Designer Laura put together. “We were just looking at real photos of flooded areas such as farmland and cities around Europe and all from recent events,” Groeneboom explains. “It’s all based on real references that are quite current. The concepts from Laura were amazing, and it was sort of a bible – its own locations and references from both the recce and the [actual] places. There’s a bunch of scenes where there are animals trapped in a bit of mud, and you just see those skeletons sticking out. It’s just in the background and you don’t notice it, but it’s everything that can tell some kind of story. Barbed wires being cut for some of the fences, just whatever environmental storytelling they can think of, we tried to put in the background for some of these shots.”

“There’s a bunch of scenes where there are animals trapped in a bit of mud, and you just see those skeletons sticking out. It’s just in the background, and you don’t notice it, but it’s everything that can tell some kind of story. Barbed wires being cut for some of the fences, just whatever environmental storytelling they can think of, we tried to put in the background for some of these shots.”

—Theodor Groeneboom, Visual Effects Supervisor

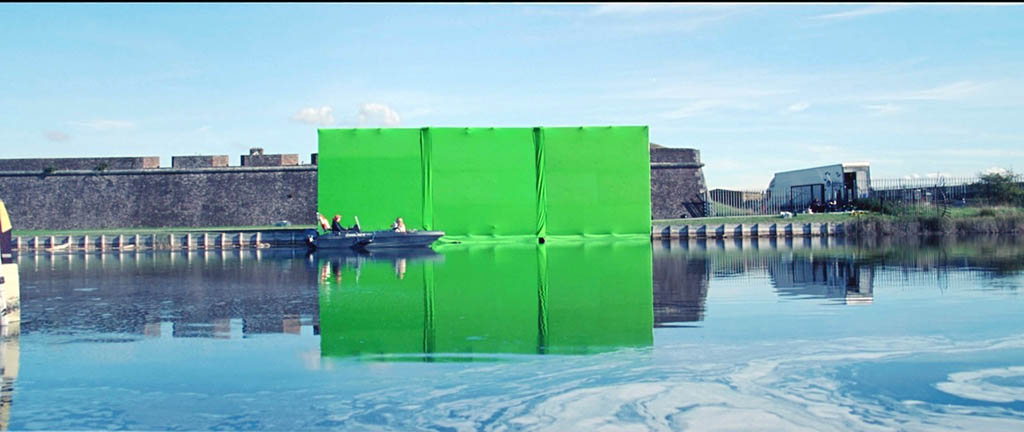

The biggest challenge for Visual Effects Supervisor Theodor Groeneboom involved trying to figure out how to do London underwater, specifically Fleet Street. Greenscreen was required to isolate key elements to be added later.

“There were loads of references we were putting into the film,” he continues. “There were references for the textural quality of the rain and how much we should use. Some of it was more on the practical side of things and how to shoot, etc. and elements we want to use. As an overarching production design bible, there was a lot of stuff that came from Laura. A lot of ideas of not strictly stuff they wanted to see in the film, but Mahalia liked the feeling of it. There’s definitely less of the 28 Days Later vibe with the military and trying to keep it a bit more chaotic and grounded in the people around Jodie.”

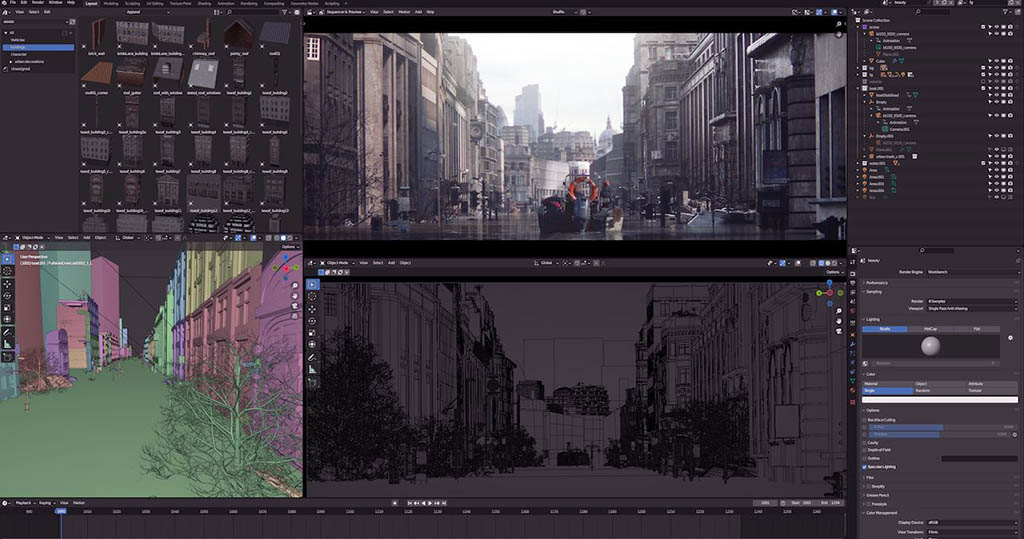

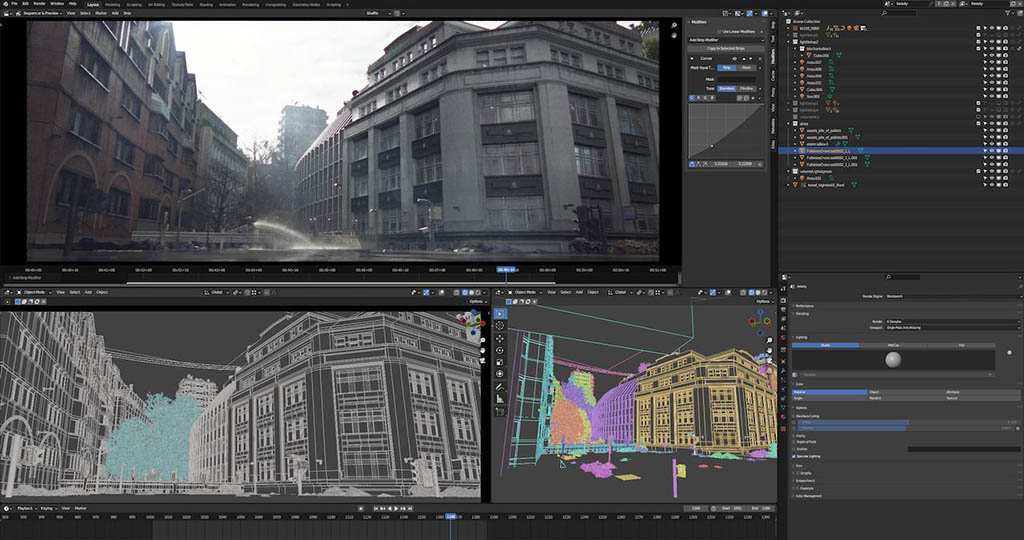

“[Fleet Street underwater] was all approached from the same angle as everything else, that it needs to be grounded in reality, and you shouldn’t really pay attention to the effects of it. You should just take in the image as this is something that’s happened. We rebuilt the whole of Fleet Street. … I was taking photographs of every single façade, building, element and item that I could find. We later modeled them up in 3D for textures and lighting ornament and rebuilt the street from scratch. There are some obvious liberties taken to make sure that lighting looks as good as it can, so there are gaps in-between the buildings just to put nice eye lights on every other building.”

—Theodor Groeneboom, Visual Effects Supervisor

Groeneboom took photographs of every single façade and building, element and item that he could find of Fleet Street, then modeled them in 3D for textures and lighting, rebuilding the street from scratch.

Belo and Lavelle had a clear vision in their heads of what they wanted to achieve. “It wasn’t specific, but they were after a certain feeling. I think the production design bible picked all the right pieces,” Groeneboom remarks. “It was Suzie who set the real textural film quality to everything with her cinematography. We did really early development, sketches of trying to make things feel like they are underwater, like a suburban submerged in the city. This was all CG stuff that we were playing with beforehand to see whether or not it was doable with a small team and the amount of resources that we had. These were all based off the same references from the production bible.”

The biggest sequence for Groeneboom involved trying to figure out how to do London underwater, specifically Fleet Street. “Underwater in whatever capacity we could do,” he adds. “I think we got there in the end. It was all approached from the same angle as everything else, that it needs to be grounded in reality, and you shouldn’t really pay attention to the effects of it. You should just take in the image as this is something that’s happened. We rebuilt the whole of Fleet Street. I was dangling off a rental bus, one of the old Routemasters, and I was taking photographs of every single façade and building and element and item that I could find. We later modeled them up in 3D for textures and lighting ornament and rebuilt the street from scratch. There are some obvious liberties taken to make sure that lighting looks as good as it can, so there are gaps in-between the buildings just to put nice eye lights on every other building. Once the light hits a certain angle on Fleet Street, it just becomes completely obscured by the buildings.”

Recreating Fleet Street proved to be a challenging task as it’s an iconic street in London that people are very familiar with. The VFX team relied heavily on the production design bible put together by Production Designer Laura Ellis Cricks.

Fleet Street proved to be a challenging task as it’s an iconic street in London that people are very familiar with. “There are so many great photo references of it as well,” Groeneboom details. “It was a matter of bouncing between what Mahalia felt was real, or what she would accept being real, and what Suzie thought of the texturing and lighting of the scene and how she would approach it from a practical point of view. Obviously, she can’t light an entire street, but how as a DP would she approach it from a practical point of view? We had lots of discussions trying to figure out the right angle for the sun, but also blocking out certain elements to create interesting patterns on one side and having the other side a bit more muted. The opening shot of that scene was quite challenging as well, just trying to make it feel like London specifically. It was shot on a little greenscreen.”

There were around 120 visual effects shots in total, with 13 or 14 of those being Fleet Street. “The film is quite slow-paced, especially in terms of number of cuts in the film. Every single little detail and item on Fleet Street was modeled up and painstakingly created. There are some hints of hope in this scene as well. For example, there are few people dotted around in the windows. The bus was a challenge as well because the chassis of the bus was not favorable to any particular lighting. If you see the Routemasters buses in the city and take pictures of them, they are just uniformly red. It’s very hard to see any shading on them. Getting some prospective lighting on them proved to be a little bit difficult, so we had to exaggerate the amount of light and shadow that the material actually has. It’s a combination of plastics and metal, so that was a bit of a faffle.”

Groeneboom studied real photos of flooded areas such as farmland and cities around Europe based on current references.

Continues Groeneboom, “[Lighting was also an issue on] quite a few shots where there is flooding on some of the signs, but it’s all CG. We rebuilt a lot of environments and tried to make it all as integrated as possible. For instance, the subtly of some of the elements, like dead animals floating. Maybe you don’t pick it up when you watch the film for the first time, but there are quite a few of these images where they are driving and there is stuff in the background. I quite like that because a lot of films I’ve worked on previously have been blockbusters and the effects are front and center, but here they are subdued in the background. One of my favorite shots is of a traffic jam. There is a giant boom mic on the windshield of the car, which was a bit of pain to remove. We just extended the whole background with a bit of the M25 in the background, and there are fires and fire trucks and lots of things happening, but you probably don’t see it. In terms of rain enhancements, it was just putting more in. On the day, you can only get rain so far close to certain things before you have to do some augmentation with visual effects because of rain. Working with real effects elements is always a bit unwieldy. We also worked on the little baby bumps as well, which are partially prosthetics and partially visual effects.”

Groeneboom and his team also worked on the little baby bumps, which are partially prosthetics and partially visual effects.

Groeneboom and his team had ample support from every department in pre-production and on set. The riggers and the gaffers were especially helpful in pulling up greenscreens if needed and accommodating for the lighting and tracking markers whenever Groeneboom and his team were able to be on set for supervision. “We were there for the most important days, but they would take our potential work into consideration by just phoning us up and asking if we need tracking markers here, for example,” he adds. “So, in terms of on the shoot, we were quite welcome and an integral part of solving some of these shots. In terms of the post-production side, it was me and my company [Rebel Unit in Bergen, Norway] doing it. SunnyMarch were producing the whole film, and they were our client for the job. We are a small team of 10-11 people. I think we had six people on this at the most. The idea of my company is most of the people working there have worked in larger facilities before, so we are trying to move away from the idea of thinking large pipelines and overcomplicating, or over-engineering things, which we are trying to do as much as we can in off-the-shelf software and just being a bit more nimble about the approach. I’m quite happy with a small team of six people doing the work. There were two of us, including myself, doing the modeling for the Fleet Street elements.”

“We rebuilt a lot of environments and tried to make it as integrated as possible. For instance, the subtly of some of the elements, like dead animals floating. Maybe you don’t pick it up when you watch the film for the first time, but there are quite a few of these images where they are driving and there is stuff in the background. I quite like that because a lot of films I’ve worked on previously have been blockbusters and the effects are front and center, but here they are subdued in the background.”

—Theodor Groeneboom, Visual Effects Supervisor

There were around 120 visual effects shots in total, with more than a dozen of those being Fleet Street.

Groeneboom concludes,“Given the fact we are a small team and what we were able to achieve, I’m quite proud of the work we did. I really enjoyed working with Mahalia. It’s her first film, and I think she’s approached it in such an interesting and inspiring manner. I’m very interested in seeing what she does next. It was also great working with Suzie, as she’s lovely to work with, and working with the production team was one of my favorite parts. Reading good reviews, and the fact that the film has an important backdrop about the state of the world is interesting. From a visual effects point of view, you tend to go with more lackluster ideas of what apocalyptic visions happen to be. I thought this felt more real and important. Also, watching Jodie perform was really cool. She’s absolutely phenomenal.”