By CHRIS McGOWAN

Images courtesy of DNEG and Universal Pictures.

By CHRIS McGOWAN

Images courtesy of DNEG and Universal Pictures.

Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) examines the atomic bomb prior to the weapon’s first test

Theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer’s time as the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II was arguably the most impactful job ever undertaken. Oppenheimer led a team of scientific luminaries as part of the Manhattan Project, which developed the first nuclear bombs, the most powerful weapons in history – changing the world forever. Oppenheimer felt great moral turmoil about his efforts, and when the Trinity test was successful on July 16, 1945, he thought, “Now, I am become death, the destroyer of worlds,” words from the Hindu scripture Bhagavad Gita.

In the movie, Cillian Murphy (as Oppenheimer) says, “They won’t fear it until they understand it. And they won’t understand it until they’ve used it. Theory will only take you so far. I don’t know if we can be trusted with such a weapon. But we have no choice.” After the end of World War II, Oppenheimer positioned himself against nuclear proliferation and the development of a hydrogen bomb, which put him at odds with many in the government and military. Christopher Nolan had long wanted to tell Oppenheimer’s story, and he has done so with a movie that is part biographical drama and part thriller, shot primarily in IMAX and best viewed on large-format, high-resolution movie screens.

Nolan dramatizes the frantic race of the American military to build the first A-bomb before the Nazis did (they were thought to be in the lead) and immerses the audience inside the brilliant Oppenheimer’s conflicted mind, from his deepest fears to imaginings of the quantum realm and the cosmos, and the fate of the planet. He alternated color with black-and-white footage – the first time B&W IMAX 65mm film stock has been used for a feature film. And, typically, he tried to avoid CGI – not an easy task when dealing with the first atomic bomb explosion.

In the fall of 2021, Nolan announced his attention to write and direct the film, with Universal Pictures as the distributor. Nolan’s script was based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin. Filming took place February to May 2022, mostly in New Mexico. Emma Thomas, Charles Roven and Nolan produced the movie, in which Murphy portrays Oppenheimer. The star-studded ensemble cast includes Emily Blunt (Kitty Oppenheimer), Matt Damon (Leslie Groves), Florence Pugh (Jean Tatlock), Robert Downey Jr. (Lewis Strauss), Kenneth Branagh (Niels Bohr), Jack Quaid (Richard Feynman), Matthew Modine (Vannevar Bush), Tom Conti (Albert Einstein) and Gary Oldman (Harry Truman). The scientists portrayed make up a veritable 20th century hall of fame for theoretical physics.

Oppenheimer was DNEG’s eighth straight film working with Nolan, and it has been the director’s exclusive outside VFX studio starting with Inception (2010). Andrew Jackson, Production VFX Supervisor, comments, “As well as having the creative experience from years of working with Chris, DNEG also has a huge benefit when it comes to solving the technical challenges of working with IMAX resolution in a largely optical production pipeline.”

Scott R. Fisher, Special Effects Supervisor, Giacomo Mineo, DNEG VFX Supervisor, Mike Chambers, VES, VFX Producer, and Mike Duffy, DNEG VFX Producer, also helped bring the movie to life. Long-time Nolan colleague Hoyte van Hoytema handled the cinematography.

Some of the techniques that the VFX team used to produce the spectacle of nuclear fission were also used to help create the scenes that portray Oppenheimer’s inner world.

“We wanted all of the images on screen to be generated from real photography, shot on film, and preferably IMAX. The process involved shooting an extensive library of elements. The final shots ranged from using the raw elements as shot, through to complex composites of multiple filmed elements. This process of constraining the creative process forces you to dig deeper to find solutions that are often more interesting than if there were no limits.”

—Andrew Jackson, Production VFX Supervisor

Oppenheimer was Andrew Jackson’s third film with Nolan, following Dunkirk and Tenet. “During that time, I have developed a strong understanding of his filmmaking philosophy,” Jackson says. “His approach to effects is very similar to mine in that we don’t see a clear divide between VFX and SFX, and believe that if something can be filmed it will always bring more richness and depth to the work.”

Christopher Nolan adjusts IMAX camera over Cillian Murphy (portraying J. Robert Oppenheimer). Oppenheimer was shot primarily in IMAX. (Photo: Melinda Sue Gordon)

Nolan challenged the VFX artists to pull off the visual effects in Oppenheimer without any computer graphics, if possible. Jackson comments, “I spent the first three months of the project in Scott Fisher’s workshop, working with him and his SFX crew to develop the various simulations and effects. We continued working closely with the SFX crew for the duration of the shoot – in fact, it was really one FX team.”

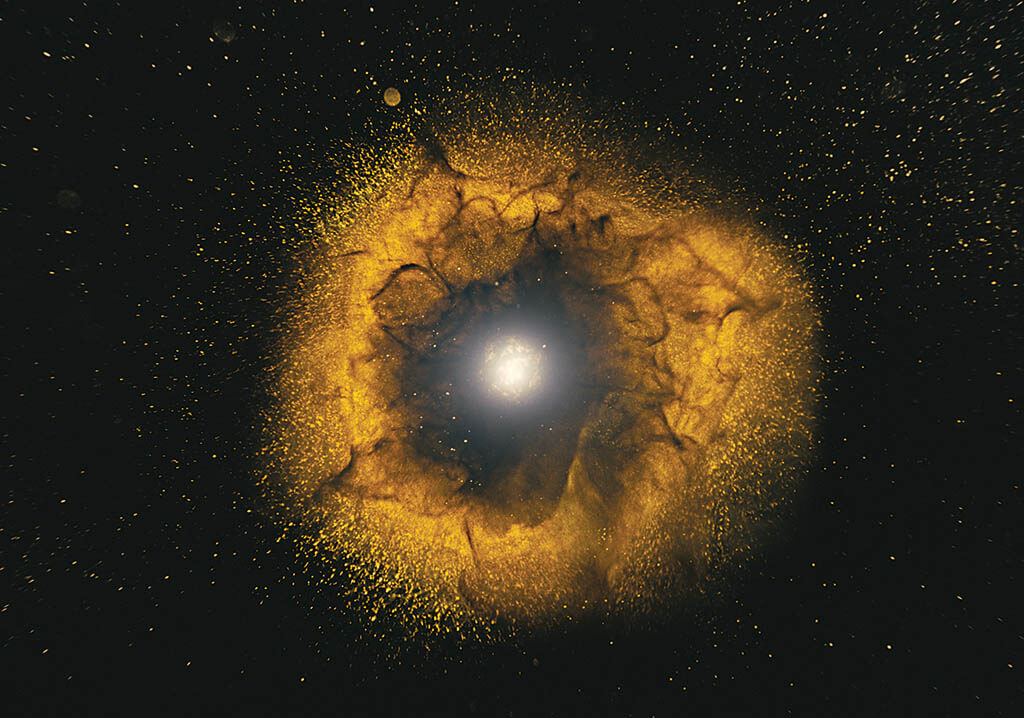

Mineo says, “The entire project was a constant creative brainstorming process, as we had to be imaginative and experimental with the footage to visualize what was in Oppenheimer’s mind. From creating the birth of stars by the talented comp artist Ashley Mohabir, to visualizing sub-atomic chain reactions and even the ‘end of the world’ scenario after the nuclear proliferation, designed by Marco Baratto, we pushed the boundaries of creativity.”

One difficulty was capturing Oppenheimer’s ideas and imagination considering the different scientific and visual references available during the 1940s. However much the scientist was a visionary, he was also a man of his time. Mineo explains, “Concepts like the Earth seen from space or modern physics were relatively new at the time. To truly portray Oppenheimer’s mindset, we had to let go of our modern understanding and delve into his world. It was a fascinating journey.”

There were about 150 total visual effects shots in Oppenheimer, 30% of which were in-camera, according to Chambers. He notes, “Being a period piece, some contemporary anachronisms were necessarily cleaned up, but only when glaringly obvious. As a general rule, pure fixes were used very sparingly.”

Mineo says, “We embraced old-style techniques such as miniatures, massive and micro explosions, thermite fire, long exposure shoots and aerial footage. The majority of the VFX work was based on these elements, without any reliance on CGI and mainly involving compositing treatments.”

Oppenheimer and his scientific team worked at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, located some 30 miles from Santa Fe, New Mexico. Mineo comments, “Surprisingly, we needed minimal interventions for Los Alamos as the town had been re-built almost entirely. Our focus primarily involved minor clean-up and retouching work for specific elements such as the tower and the bomb.”

Chambers notes, “Some of the magic was intercutting the magnificent set that [Production Designer] Ruth De Jong designed and built with some of the actual locations in Los Alamos itself, including the Lodge and Oppenheimer’s actual house.”

Placing a premium on practical effects, the VFX team generated a library of idiosyncratic, frightening and beautiful images to represent the thought process of Oppenheimer, who was at the forefront of the paradigm shift from Newtonian physics to quantum mechanics, looking into dull matter and seeing the extraordinary vibration of energy that exists within all things.

Atomic Energy Commission Chairman Lewis Strauss (portrayed by Robert Downey Jr.) carried a grudge against Oppenheimer. The film alternated color with black-and-white footage, and it marked the first time B&W IMAX 65mm film stock was used for a feature film. (Photo: Melinda Sue Gordon)

Christopher Nolan lays out the scene for Cillian Murphy, who portrays Oppenheimer. (Photo: Melinda Sue Gordon)

The VFX team was in sync with DP Hoyte van Hoytema. Jackson says, “Throughout the production process we worked closely with Hoyte experimenting, testing and developing ideas to illustrate the concepts in the script. On this project we worked with him and the camera department to develop an IMAX probe lens specifically for some of the FX elements. Hoyte also built some extremely powerful LED lights that we used in the tank shoot.”

The Trinity nuclear explosion was done without any CGI. “We knew that this had to be the showstopper,” Nolan told the Associated Press. “We’re able to do things with picture now that before we were really only able to do with sound in terms of an oversize impact for the audience – an almost physical sense of response to the film.”

A young Oppenheimer. The filmmakers had to be imaginative and experimental with the footage to visualize what was in the physicist’s visionary and conflicted mind.

Explains Chambers, the team strove to “determine how best to illustrate various aspects of a nuclear explosion without relying on CG VFX, stock footage, or actually setting one off.” The Trinity test was recreated using real elements. Mineo remarks, “We only had the original footage of the Trinity explosion as a precise reference. Chris Nolan was determined to keep the VFX grounded in reality and maintain the raw feeling of the actual footage.

We had to find the right balance, striving to be minimal with our treatments while ultimately recreating such a massive event. Our talented team of compositing artists, including Peter Howlett, Jay Murray, Manuel Rivoir and Bensam Gnanasigamani, did an exceptional job working for months to create this iconic moment in history.”

Chambers adds, “Though there were a few shots using 2D compositing in order to utilize multiple elements, all elements were acquired photographically. For some effects, large pyrotechnical explosions were set off in the desert, however for some views we also used a variety of cinematic tricks, including cloud and water tanks, forced-perspective miniatures and high-speed photography for scale.”

For Chambers, “One of the big challenges for me specifically was the logistics of experimenting and shooting our elements and gags while traveling to all the locations and working alongside the main unit throughout principal photography. Though we didn’t have the luxury of a fixed stage for our work, the advantage of having the director at hand to review and expand on our ideas in real-time was priceless.”

Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) in an emotional moment with his wife (Emily Blunt) at Los Alamos. (Photo: Melinda Sue Gordon)

General Leslie Groves (Matt Damon), who was in charge of the Manhattan Project, confers with Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) at Los Alamos. (Photo: Melinda Sue Gordon)

Oppenheimer, in the searing light of his creation, at the Trinity test in New Mexico. The explosion was recreated using real elements and no CGI. Nolan wanted to take the audience “in the room” when the button is pushed

Theoretical physicist Edward Teller (played by Benny Safdie) at the Trinity test. (Photo: Melinda Sue Gordon)

Director Chris Nolan with his long-time colleague, DP Hoyte van Hoytema, who is wielding an IMAX camera. The visual effects team worked with van Hoytema and the camera department to develop an IMAX fish-eyed probe lens specifically for some of the VFX elements. (Photo: Melinda Sue Gordon)

Some examples of Oppenheimer gags, according to Chambers, included “a special rig designed to spin beads on multiple axes, a special rig designed to recreate the effect of an implosion, and a special tabletop rig to recreate the effect of a ground-based shockwave. Some of these were relatively simple setups and others were more complex. Some were used as shot in-camera and others were combined with traditional elements to complete the shots. As the nature of our approach was primarily physical and tangible, Scott [Fisher] and the SFX crew helped to devise and create the various rigs and gags that we wanted to shoot.”

Director Nolan also sought a deeper immersion by employing IMAX, his preferred format. “The headline, for me, is by shooting on IMAX 70mm film, you’re really letting the screen disappear. You’re getting a feeling of 3D without the glasses,” Nolan told the Associated Press.

Chambers notes, “We used both IMAX 65mm and [Panavision Panaflex] 5perf 65mm film formats. 5perf was sometimes used for more intimate dialogue scenes as the IMAX cameras are not as quiet on the set. On the VFX unit, we also used some 35mm for extreme high-speed photography.”

Mineo adds, “IMAX is undeniably the most cinematic format, but it poses unique challenges for VFX due to its incredibly high resolution. At DNEG, we have a well-designed pipeline that caters to the IMAX workflow, thanks to our experience collaborating with Chris Nolan since our work on Batman Begins. As for the black-and-white footage, our color science team, led by Mario Rokicki, seamlessly adapted our pipeline to accommodate it.”

Jackson remarks, “The two biggest challenges were also the most rewarding aspects of working on this movie. Firstly, the script describes thoughts and ideas rather than specific visual images. This was both exciting and challenging as we searched for solutions we could build and shoot that were both inspired by the ideas in the story and were visually engaging.”

Continues Jackson, “The second challenge was the set of creative rules that we imposed on the project. We wanted all of the images on screen to be generated from real photography, shot on film, and preferably IMAX. The process involved shooting an extensive library of elements. The final shots ranged from using the raw elements as shot, through to complex composites of multiple filmed elements. This process of constraining the creative process forces you to dig deeper to find solutions that are often more interesting than if there were no limits.”

Mineo concludes, “One of the highlights was the opportunity to learn a different way of creating VFX. Understanding how Chris Nolan thinks and approaches his movies allowed us to bring his unique philosophy into our way of working. Initially, it presented some challenges and limitations, but the result is unquestionably real, 100% believable, and ultimately more satisfying.”