By MARK J. MILLER

By MARK J. MILLER

Broadway has had its share of visual effects extravaganzas – live elephants, aerial battles, a full-blown chariot race – but it’s never had a 20-foot, 1.1 ton ape wandering across one of its stages. Until now.

King Kong debuted on the Great White Way in early November 2018 after 10 years of development and $35 million in investment. A good chunk of that cash went toward figuring out a way to make that big ape as realistic as possible. The show’s amazing visual effects are the key to this production’s survival. Kong is what the audience has paid its money to see.

Part of the joy of Broadway, of course, is the visual sleight of hand designers bring to each show, whether it is a helicopter dropping into Miss Saigon, the massive chandelier swinging dramatically to the stage from the theater’s high ceiling in Phantom of the Opera, or actors parachuting from a plane and dropping to the stage in The Who’s Tommy.

Audiences are much more demanding now for wow moments, but the idea of “spectacle” is relative. “When there’s a technological advance that can be incorporated onstage, the theater quickly harnesses it and exploits it,” says Laurence F. Maslon, Arts Professor at NYU’s Graduate Acting Program. Audiences came to see shows in the 19th century simply because the sets had doors and windows that opened and closed. When it became possible to cook an actual meal onstage, audiences came to see that as well.

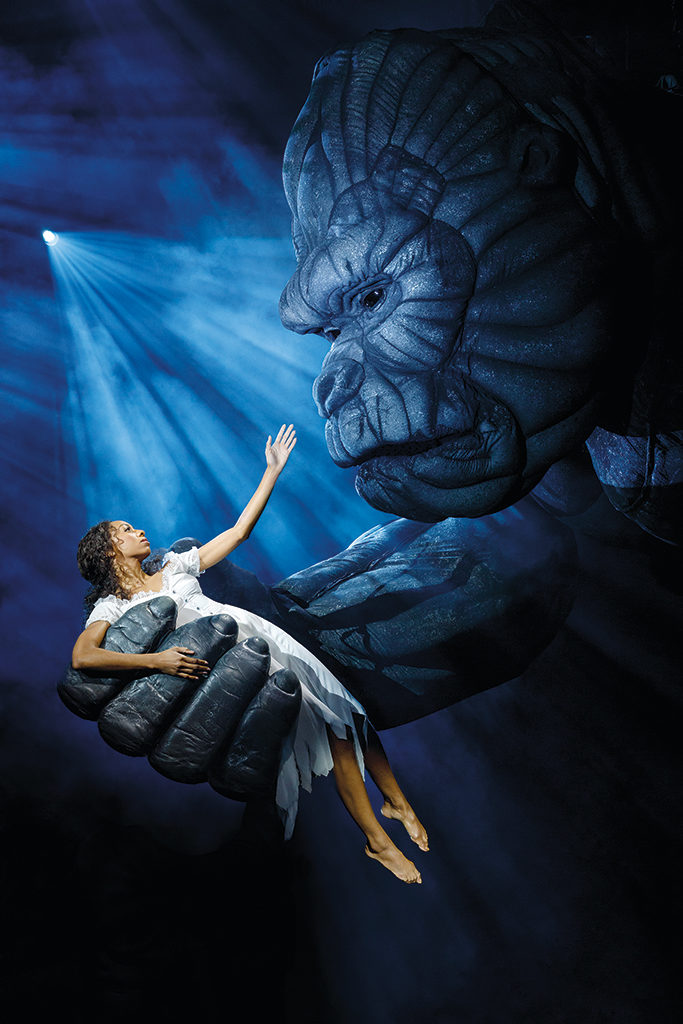

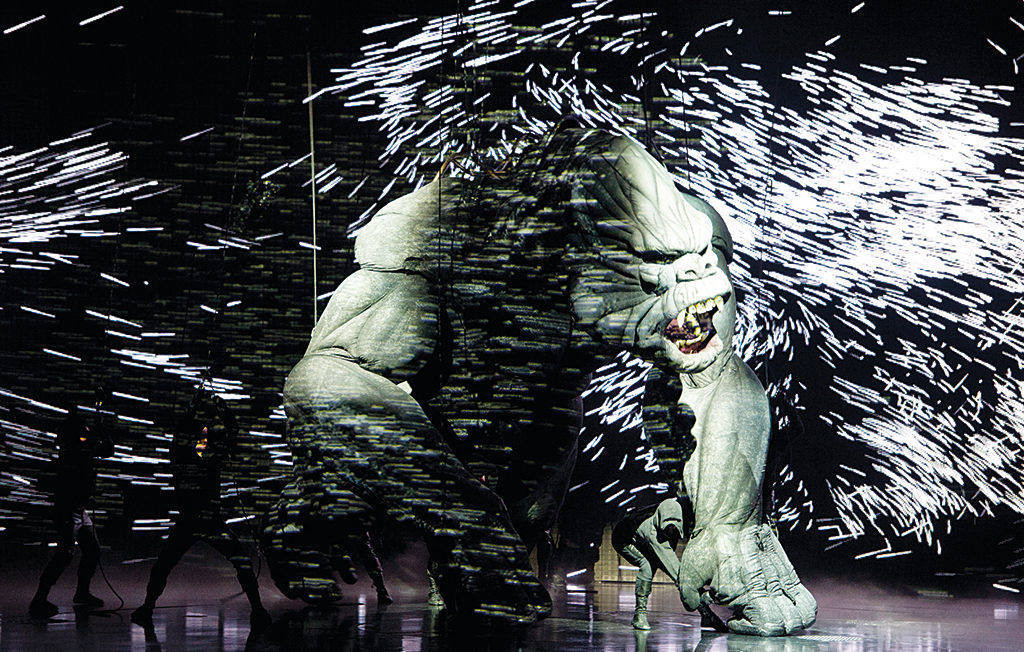

Bringing this 20-foot, 1.1-ton behemoth to life on Broadway are 14 puppeteers and computer technicians, along with 16 microprocessors, 16,000 connections, and nearly 1,000 feet of electrical cable built into the beast. Kong took years to perfect through concept design, prototyping, and testing, but the final version took about six to eight months to construct, according to Creature Designer Sonny Tilders, the man who led the team that built the ape. Ten of the puppeteers are known as the King’s Company and move with the beast onstage, using their weight and movements to move Kong’s lower body and arms.

When the ape needs to lift an arm high, one puppeteer climbs up his back and dives from his shoulders with a rope in hand to help create the effect. These 10 actors are also part of the cast when not on Kong duty.

There were times, of course, when it didn’t seem like it would ever get to this point, says Tilders. “This was a daunting task to do for the stage and concerns grew at the start of the project that it might just be too difficult,” says the man who is plenty comfortable working with big puppets. He’s the creative director of Australia’s Creature Technology Company, the outfit responsible for designing and building the full-size animatronic dinosaurs in the arena show, Walking With Dinosaurs, that launched in 2007 and proceeded to wander across four continents.

“Our history as a company was one of making very realistic creatures with an attention to detail and sophistication of movement usually reserved for film animatronics,” Tilders says. “Apart from anything else there was a risk that the technology would overshadow everything we were trying to achieve dramatically,” he says. It also wasn’t clear how the initial Kong design would work with actors on the stage, so the concept of being as realistic as possible was scrapped and the team moved toward a more theatrical outcome.

One of the inspirations for Kong and the King’s Company came from the 2007 play War Horse, which featured nine full-size horse puppets, each controlled by two or three people onstage. “Puppeteers seen openly manipulating the stunning horse puppets quickly disappear as they become one with the creatures they are controlling,” Tilders says. “It gave us the confidence to embrace exposed puppeteering solutions.”

“Our history as a company was one of making very realistic creatures with an attention to detail and sophistication of movement usually reserved for film animatronics. Apart from anything else there was a risk that the technology would overshadow everything we were trying to achieve dramatically,”

—Sonny Tilders, Creature Designer

However, this simple old-school form of puppetry is married to the highest technology theater has seen. “We thought embracing more traditional puppetry techniques would provide more practical low-tech solutions,” Tilders says. “The result is a hybrid of new and old technologies, both manual and mechanical. Kong evolved into a giant string puppet – albeit one jam-packed with hidden tricks and technology.”

Four people known as Voodoo Operators control a fair amount of that technology. They sit in a booth in the back of the theater up in the balcony using computers to control Kong’s eyebrows and eyelids, mouth, nose, shoulders, jaw and hips. One member of the team also serves as the voice of Kong through a processor that lets each gentle grunt, curious growl and enraged roar sound as if it’s coming from a massive ape rather than from a mere human. Three of the Voodoo Operators also appear on stage in larger group scenes.

Another member of the Voodoo Operators is the creative engineer. He spends the show monitoring all of Kong’s onboard systems, such as hydraulic oil pressures and temperatures, motor temperatures, air pressures and general creature diagnostics. “He’s there to make sure the monkey behaves itself,” says Tilders. Kong is too big to fit into the wings of the stage, so he is lifted into the flyspace above the stage when he’s not needed.

Kong’s realism was key to actually getting the show onto Broadway. Director and choreographer Drew McOnie flew from London to Australia to meet the ape before taking the job. After all, he needed to see if he could work with his star. “This probably makes me sound like a complete weirdo, but he’s definitely got an aura that has something to do with his eyes,” he told the New York Times. “He ends up reflecting the person he’s looking at, and that ends up feeling very theatrical and very beautiful.”

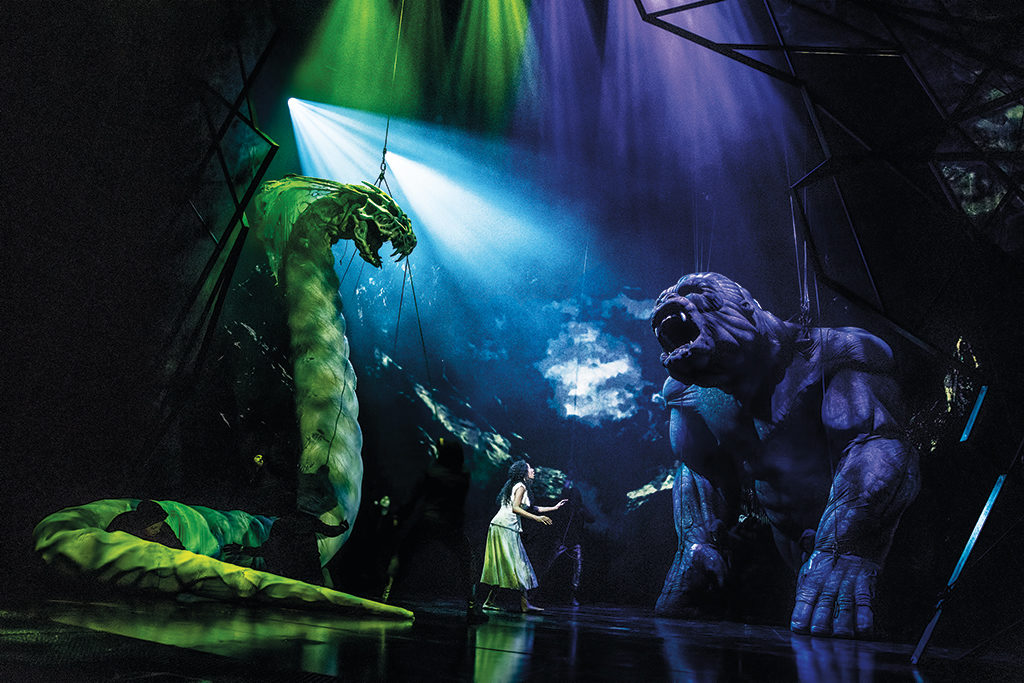

The actual gargantuan ape isn’t the only visual effect to gape at in the show. King Kong features a few other fascinating effects, including a battle with a 40-foot snake and the integration of a 90-foot video screen. “Bringing all the different departments together as well as integrating the actors is what makes it all really work from the technical side,” notes Peter England, the Scenic and Projections Designer. “Working with massive video screens and giant puppets makes things more interesting for actors these days.”

“I knew that with our surround LED screen I could then start playing around with horizon lines, waves and clouds to further enhance this sense of travel and motion dynamic. Combining all these factors I felt we could theatrically create a large boat that ‘moved’ believably – and quite possibly a boat that the audience might also feel they were on with us.”

—Peter England, Scenic and Projections Designer

1899-1900 Ben-Hur. The production featured “two real chariots tethered to two live horses, who were themselves tethered in place to a treadmill that cranked the moving cyclorama behind them,” according to Laurence F. Maslon, Arts Professor at NYU’s Graduate Acting Program.

1935-1936 Jumbo. Staged by showman Billy Rose at the massive Hippodrome, the show was set at a circus and featured a live two-ton elephant.

1946 Around the World in 80 Days. Adapted by Orson Welles, the musical had four mechanical elephants, a train chase, a flying eagle, and five filmed segments shown on a screen near the stage.

1993-1995 Kiss of the Spider Woman. Created by Kander and Ebb with a book by Terrence McNally, this was the first show to use pixelated projections.

2010-2014 Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark. At a cost of $75 million, the most expensive Broadway show in history, this musical wasn’t loved by critics but did feature phenomenal visual effects, particularly battle scenes fought in the air over the audience. Unfortunately, several actors were hurt in the process.

2011-2013 War Horse. This play featured life-size horse puppets that were controlled onstage by three puppeteers. By play’s end, though, theatergoers could be convinced that the horses were real.

Before theatergoers meet Kong, the main characters of Ann Darrow (Christiani Pitts) and Carl Denham (Eric William Morris), the film director who initially just wants to capture Kong on camera, hop onto a boat to go find the great ape. The full expanse of the 27-inches-tall, 90-feet-wide semi-circular ROE screen called New Linx 9 creates the effect. The screen is filled with an ocean view and part of the stage is lifted to create the illusion of a boat’s prow cutting through the water. England and his team chose this particular setup because it is relatively lightweight, weighing just over 6,600 pounds and is very flexible. The panels are 12 inches wide x 48 feet long, which allowed some freedom to place any needed openings. The power and data is onboard rather than remote, which reduces cabling, and it’s fanless, so it’s quiet, an important element for the theater-going experience.

England chose imagery that he thought looked “painterly.”

“My decision to create artwork that looked painted was motivated by the over-arching goal of the production to feel ‘hand-made’ and driven by human labor,” he says. “A welcome side effect of this painterly approach was that the imagery has an inherent softness to it and largely gets around the ugly pixilation that so often curses LED screens as a result.”

One of the design concerns in the boat scene was creating the illusion of the size of the boat. “ In the original story the boat journey from New York to Skull island is epic,” England says. “It is a massive three-month journey into the unknown. From the outset it was considered essential we meet this epic quality on stage.” Since there were a few scenes and a large song-and-dance number, as well as the need for it to appear to be a boat big enough to cart a giant gorilla across the waters, the design of the boat became a challenge. That led to the idea of a small bit toward the rear of the stage being lifted to create a triangular ramp that gives off the idea of the ship’s prow. That lift point stays set for the entire trip on the boat. With the lift machinery, the motion of the actors and the water on the screen, it gives the sense of rhythmic movement. “I knew that with our surround LED screen I could then start playing around with horizon lines, waves and clouds to further enhance this sense of travel and motion dynamic,” England says. “Combining all these factors I felt we could theatrically create a large boat that ‘moved’ believably – and quite possibly a boat that the audience might also feel they were on with us.”

“In many ways what we did was utilize some simple movie-making techniques that have their origins way back around the time when the original Kong movie came out.”

—Peter England, Scenic and Projections Designer

Once the island is reached and the characters meet Kong, other big visual effects surprises lay ahead, such as the massive snake and its fight with Kong. The snake has six puppeteers onstage alongside Kong’s 10. The fight moves off stage and then appears as if the action is between large shadow puppets. “The shadow puppetry is actually done with front projection onto the painted PVC and steel scenic drop which is concealing some rapid de-rigging of both creatures upstage,” England says. Each creature was photographed separately and then a series of still images were compiled to show them “fighting” while stormy-lightning strobe effects are filling the theater. There are four groups of 20 images that are played in about six seconds. England compares the result to stop-motion animation.

The show culminates, as the original 1933 film did, with Kong escaping his captors, running through the streets of New York, climbing the recently constructed Empire State Building and doing battle with gunmen on planes. While the film famously used Willis O’Brien’s stop-action animation, the Broadway show employs other effects to create the scene. The run through the streets is basically a marriage between the screen and the puppet. Kong runs and jumps in one spot while the screen imagery moves and leaps and shifts and changes to make it appear that Kong is moving quickly through New York. “In many ways what we did was utilize some simple moviemaking techniques that have their origins way back around the time when the original Kong movie came out,” England notes. He uses the example of a camera shot through the front windshield of a couple ‘driving’ in a stationary car. Visible through the car’s rear window is pre-shot footage of streets trailing off in the distance, creating the impression that the couple and the vehicle are actually moving.

For the climb up the Empire State Building, window framing is projected onto fabric stage center, and audience members can look through to see Kong suspended in the background. The puppeteers have his arms and legs moving in a climbing motion while his body swings from side to side. Meanwhile, the LED screen shows animated content as Kong moves higher through New York City’s skyscrapers. “The speed at which this content rises is matched to the speed at which the front projected windows descend – and both speeds are motivated by the speed at which Kong’s climbing action can be performed,” England says. “Supporting all this is the music tempo – sound being a critical element to selling all of these visual motion dynamic moments.”

Critical to making it all work, England says, is having some automation to build around. The King’s Company and Voodoo Operators can do their thing live each night, but England can’t change the timing of his animations or the length of the boat ride film. “The automation component, which controls the puppet’s entrances, exits and gross moves around the stage, is a series of pre-programmed cues and the same every show,” he says. “This is the ‘anchor’ we needed to ensure synchronicity.” The auto cues are called by the stage manager and have set timings to them so the team was able to accurately build its content-animation cues to match the auto cues.

According to Tilders, the ability to adjust the automation to the live environment is a vital element. “This meant we could keep the puppet alive and reactive to the variability that occurs in any live show, in particular that which comes from needing to act alongside humans,” he says.

Still, while the other visual effects are impressive, the main attraction is Kong. One of the show’s more potent moments occurs when the only performer onstage is Kong (and his puppeteers). The music and dancing have stopped and Kong moves right up to the lip of the stage. It appears that he is going to come right into the audience, and theatergoers are rapt. Kong reaches out and the audience gasps, unsure what he’ll do and where this amusement-park-ride of a show will take them next. For that moment, after all the behind-the-scenes work, Kong is truly king.