By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Toho Company.

By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Toho Company.

An effort was made to heighten the fear by bringing Godzilla closer to the characters.

Not since Neill Blomkamp released District 9 in 2009 has an international production received receive Academy Award and VES Award nominations for its visual effects work. But Takashi Yamazaki has repeated the feat by stomping through the box office beyond Japan along with an iconic kaiju that has been cinematic staple since 1954. Godzilla Minus One revolves around a World War II kamikaze pilot suffering from survivor’s guilt having a re-encounter with the title character, which has gone through further mutation because of American nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll.

It was always important to convey the proper scale, which meant at times only showing parts of Godzilla in the frame.

“In the current digital era, we tried to use technology that could only be used digitally. We have a lot of close-up shots of Godzilla to instill fear in the audience because it’s quite rare in Godzilla films for Godzilla to appear in the same scenes as people. We made it possible because of the high level of detail we included in the CG.”

—Takashi Yamazaki, Director/Screenwriter/Visual Effects Supervisor

Visual and special effects have dramatically evolved like the creatures in the Godzilla franchise. “In the current digital era, we tried to use technology that could only be used digitally,” notes Yamazaki, who was previously responsible for the live-action adaption of Parasyte. “We have a lot of close-up shots of Godzilla to instill fear in the audience because it’s quite rare in Godzilla films for Godzilla to appear in the same scenes as people. We made it possible because of the high level of detail we included in the CG. On the story side, 1954 Godzilla does a great job balancing the human drama with the Godzilla scenes; therefore, we were mindful in trying to have strong story and character development, and to make sure that it’s woven together with what Godzilla is doing on screen.”

The art department created a period-appropriate street surface, sidewalks and storefronts in a parking lot.

Along with being the director, Yamazaki was the Visual Effects Supervisor on the project. “Let me add screenwriter to that as well! Being all three had its benefits, although having said that, when I went to shoot on location, I wanted to ask the writer why he wrote in that specific scene because it was so difficult to shoot! When we went into post, I wanted to ask the director why did he shot the scene in that particular way because it made the visual effects that much more challenging! But of course, I only have myself to blame for all of it!” The different roles had an influence on each other. “Normally, when I write a screenplay, I have to pay some consideration to the visual effects team. Can they achieve this scene? However, in this instance I decided to trust my future self for the sake of efficiency. In post-production, because the director was the one and same as the visual effects supervisor, it allowed for more trial and error in the same amount of time. We were able to avoid any miscommunication or difference in creative direction when it came time for approvals.”

Atmospherics were a big part in creating the proper mood for shots.

Godzilla was treated as both a god and monster, which had to be reflected in the movements and physique.

“[I]n this instance I decided to trust my future self for the sake of efficiency. In post-production, because the director was the one and same as the visual effects supervisor, it allowed for more trial and error in the same amount of time. We were able to avoid any miscommunication or difference in creative direction when it came time for approvals.”

—Takashi Yamazaki, Director/Screenwriter/Visual Effects Supervisor

“We watched various Godzilla movies again and learned what makes everyone think, ‘This is Godzilla,’” Yamazaki explains. “We analyzed a great deal of photos and videos for historical background. The assistant director’s team collected a variety of background materials, and I remember being terrified that we could no longer use existing materials. Once we had a clear picture of what was going on at the time, we couldn’t just fudge it.” Storyboards drove the design process. “I drew everything that involved visual effects. It was a huge amount of work. The assistant director [Kôhei Adachi] and Kiyoko Shibuya [Visual Effects Supervisor at Shirogumi, which was the sole vendor] were very impatient with me! Basically, there was no such thing as concept art. Based on the storyboards, I set up the scenes and created previsualization with some staff members using simple CGI. From that point on, I sat next to the CG artists and gave them direct instructions if they were not going in the direction I was aiming for. If something is closely related to the shooting, I made it before the shooting starts. However, if it was necessary to include it in the editing, after the shooting is over [for example, a full CG shot], I made postvis in the same way to set the rhythm of the editing.”

A lot of time and effort were spent developing the walk of Godzilla.

The dorsal fin was made more acute and the legs thicker to emphasize the ferocious nature of Godzilla.

The camera circling around Godzilla while its holding and crushing the heavy cruiser Takao was an extremely complex undertaking. On land, trains got the same treatment, though no water was involved.

The overall silhouette of the creature is based on the previous Godzilla suits. “The dorsal fin is more acute and the legs are thicker to give a more ferocious impression,” Yamazaki remarks. “We tried to heighten the fear by making Godzilla closer to the characters, so we included many fine details to allow the camera to get closer to the characters.” No motion capture was utilized in the animation of Godzilla. “However, to help define Godzilla’s look, the animator and I spent a lot of time testing Godzilla’s walk. In Shin Godzilla, Godzilla’s posture feels very straight and uptight. In Hollywood, Legendary’s Godzilla feels more aggressive, like an animal ready to pounce. But we wanted something different from both of those. In Japan, Godzilla represents both God and Monster, so we wanted its movement to feel almost divine or God-like. We adjusted the height of its waist, how it moves and its posture many times before arriving at its current design,” Yamazaki states.

“Basically, there was no such thing as concept art. Based on the storyboards, I set up the scenes and created previsualization with some staff members using simple CGI. From that point on, I sat next to the CG artists and gave them direct instructions if they were not going in the direction I was aiming for.”

—Takashi Yamazaki, Director/Screenwriter/Visual Effects Supervisor

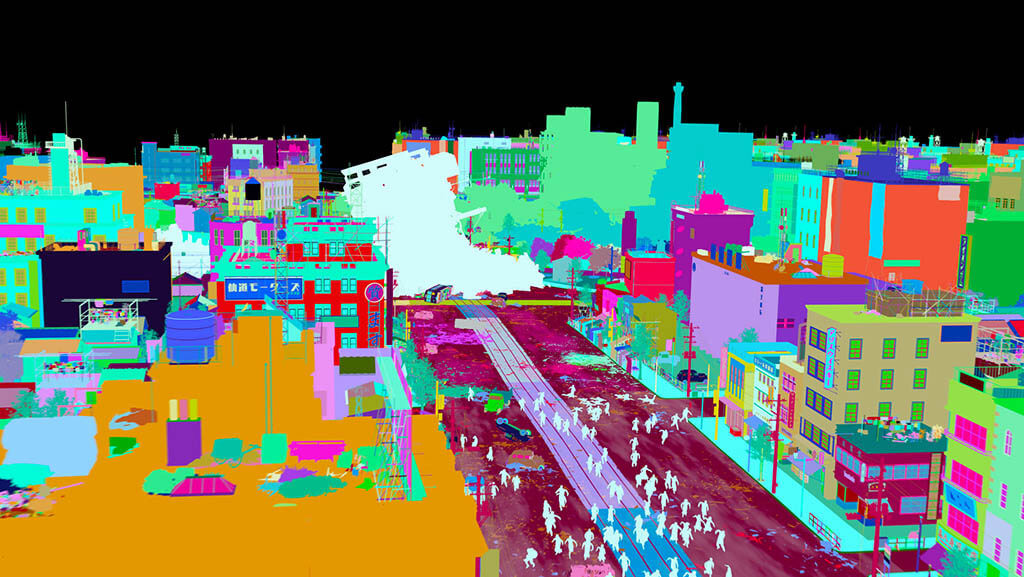

Breaking the down the destruction that Godzilla causes in the Tokyo shopping district of Ginza.

As for the world-building, it was important to transport audiences back to 1947. “We collected a large number of photos and videos from that time and were conscious of recreating the atmosphere of that period,” Yamazaki explains. “We could not use any existing open sets, and we did not have the budget to construct new buildings, so we created a composite of a digital building on a simple road set. It was difficult to make the two fit together.” The visual effects shot count is misleading. “Although there were 610 cuts, screentime amounted to two thirds of the entire film. Production time was roughly eight months after the shoot was over and in full swing. Although several people were involved in modeling and scene design before the shoot.”

“In Japan, Godzilla represents both God and Monster, so we wanted its movement to feel almost divine or God-like. We adjusted the height of its waist, how it moves and its posture many times before arriving at its current design.”

—Takashi Yamazaki, Director/Screenwriter/Visual Effects Supervisor

The first ocean battle was the most complex scene to execute. “We wanted to shoot this on location at sea because I felt it gave the picture this cool documentary style,” Yamazaki reveals. “What I didn’t expect is that everyone got seasick, and the weather was quite unstable, which made filming difficult. Once we took the footage back to the office, the natural waves that we captured were both beautiful and complex, which made it difficult making a giant creature swim through it creating its own waves. With that said, filming on one location and overcoming this challenge unified the team, and that natural imagery we were able to capture made the shot more powerful and convincing. Would I write an ocean scene into my next screenplay? That’s debatable!”

Compositing explosion and environmental elements together to create the final shot.

Simulating the ocean was hard because of the amount of data and work to make it appear believable. “A young staff member showed us a simulation of the ocean that he had made as a hobby using his home-made computer,” Yamazaki recalls. “It was so good that we rewrote part of the scenario and increased the number of ocean scenes considerably. However, in the latter half of the work, I regretted why I did that. We didn’t have a server with plenty of data to store it, so we had to make do by deleting cuts as they became available. I was astonished when I was told that the total amount of data exceeded one peta!” A personal favorite is Godzilla emitting a heat ray and destroying the entire Ginza area. Yamazaki comments, “Including the gimmick of the dorsal fin and the depiction of the area after it is destroyed, I believe I was able to create a heat ray that is more powerful and more horrific than ever before; that is a proper metaphor for the atomic bombing.”

Watch these fascinating videos on the history of Godzilla, the making of Godzilla Minus One and the production of the VFX behind the film. Click here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rIZRvKsnqtU, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vvuD5bPYimU, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CQZPh-tnH5o/