By IAN FAILES

By IAN FAILES

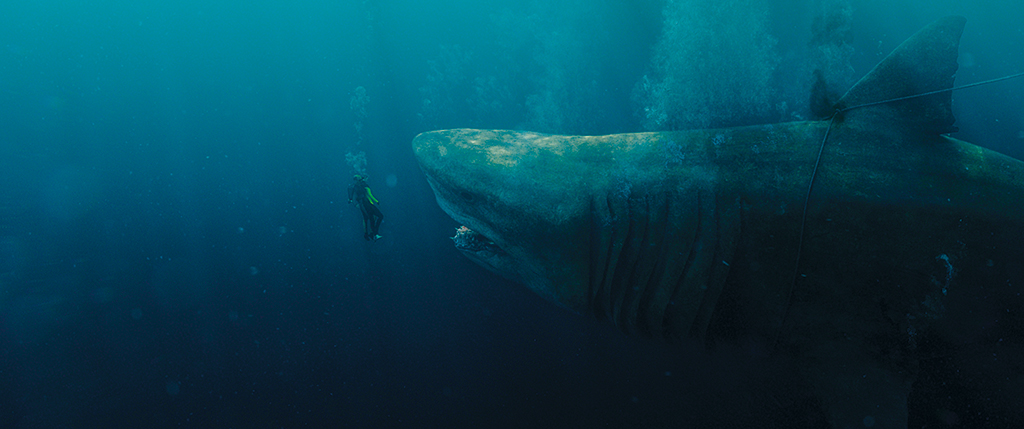

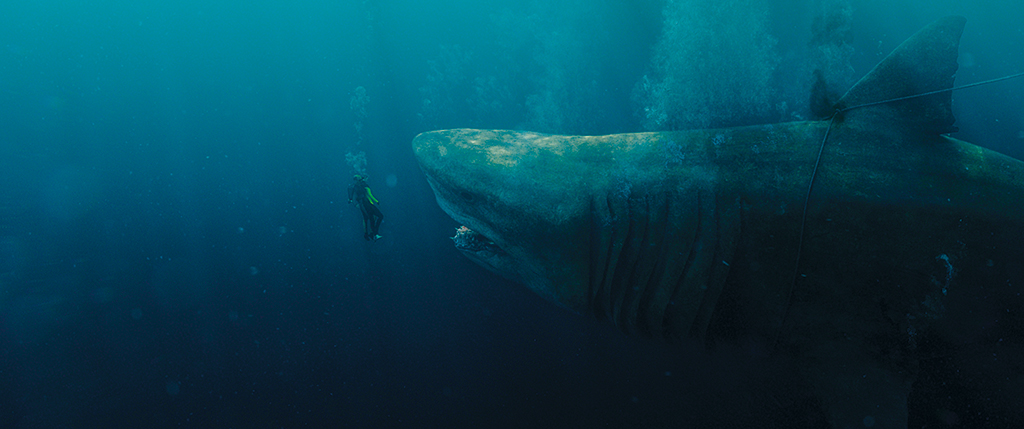

Is Hollywood obsessed with shark movies? Jon Turteltaub’s The Meg, which features a 70-foot-long monster, is the latest in a string of recent films that have seen hapless beach-goers, sea adventurers and divers meet their match against the ultimate ocean predator.

While Steven Spielberg’s Jaws utilized a not-always-working practical shark to menace the characters and audiences, most modern shark movies depend on CG. But what makes a CG shark work? VFX Voice asked visual effects supervisors from several recent shark-related productions about how they went about the task.

In visual effects, some studios tend to become particularly well known for a certain type of effects work. After the release of Joachim Rønning and Espen Sandberg’s Norwegian feature film Kon-Tiki in 2012, Swedish studio Important Looking Pirates (ILP) quite possibly assumed that mantle in relation to CG sharks. Here, they produced sharks both in and out of the water and incorporated them into more of a documentary-style story than a horror film or thriller.

“The shots were for a very important sequence during an emotional peak of the movie,” says ILP Visual Effects Supervisor Niklas Jacobson. “They needed to look absolutely convincing in order to not take the audience out of the drama.”

Jacobson says ILP had almost no character animation experience prior to Kon-Tiki, but launched into an ‘epic’ research project by reviewing shark footage from television series such as Planet Earth. The ultimate result – which saw much of the shark action actually out of the water – was so successful that ILP was asked to create digital sharks for more projects, including commercials and other feature films such as Jaume Collet-Serra’s The Shallows, in which a great white terrorizes an injured surfer stuck on a rocky outcrop.

Although ILP’s experience in these two projects and others has been in crafting photoreal digital sharks, Jacobson says this process is greatly enhanced whenever any practical stand-in can be utilized on set, both for performance and water interaction. “If you can run a gray ball or a rubber shark or anything else under the water surface to get a feel for how the caustics play and how the depth fog falls off, that is a nice bonus,” Jacobson states. He adds that then it is a matter of studying all the reference material possible.

“Key to realistic motion is great references of shark behavior and movement,” he notes. “The closer references you find to what you are trying to accomplish, the less brute genius mad skills you need to possess.”

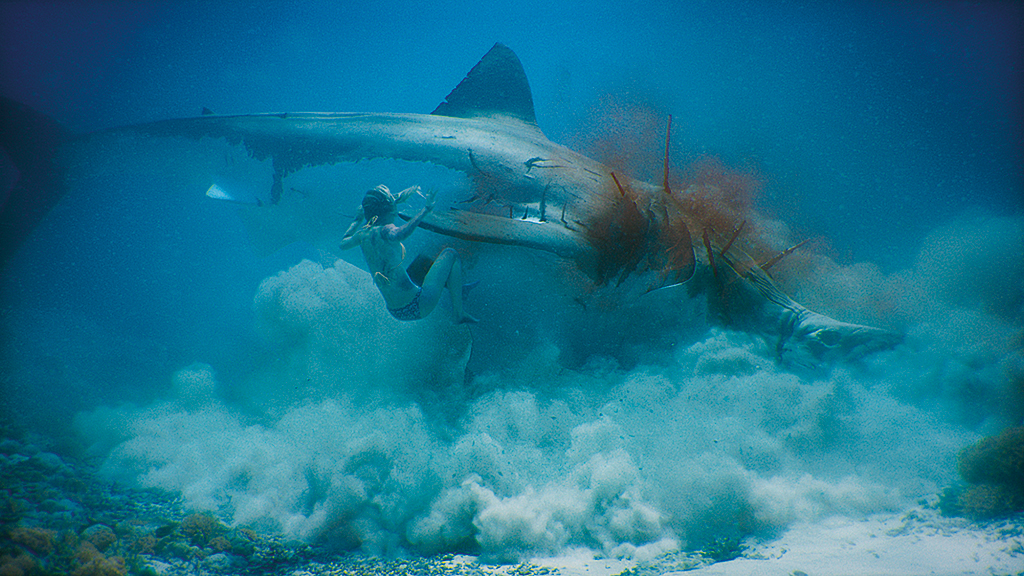

In Johannes Roberts’ low-budget horror film 47 Meters Down, two sisters get trapped on the sea floor while cage diving only to be stalked by several great whites. UK-based Outpost handled the CG sharks. Reference was their starting point, but an initial challenge also included inserting the digital assets into water tank footage.

“The water had a specific murky look with lots of small particles floating about and some volume rays coming from the surface, and it was challenging to set a CG shark within this environment,” outlines Outpost Senior Visual Effects Supervisor Marcin Kolendo. “Our 3D department did a great job of creating a realistic shark asset. Every day I saw tons of reference footage on their screens, ranging from the Blue Planet-type of professional documentaries to lots of amateur footage, especially cage-diving among sharks.”

As ILP had done for Kon-Tiki and The Shallows, Outpost also had to craft believable water simulations for their shark scenes as the creatures pierced the surface. The studio also spent a significant amount of time establishing the right look of shark skin, especially when the sharks would surface above the water. “Glistening in the sun, wet, yet rubbery and strong; there is always a lot you can do in comp, but when the CG skin shaders are wrong it will never look good on the screen, regardless of the amount of work from the 2D department,” says Kolendo.

Like many shark movies, 47 Meters Down portrays its sharks in a slightly exaggerated way, i.e. with more aggression. But Outpost worked with the director to retain as much of the ‘classic’ aspects of shark behavior as possible while still creating the feeling of terror and panic for a horror film. Says Kolendo: “We looked at how the jaws behave when a shark attacks, what the gills are doing when it turns in anger, how fast is the tail moving to propel the massive body, and then we added that extra few percent to exaggerate the action, creating a shark that is not only believable, but also terrifying.”

“Key to realistic motion is great references of shark behavior and movement. The closer references you find to what you are trying to accomplish, the less brute genius mad skills you need to possess.”

—Niklas Jacobson, Visual Effects Supervisor, ILP

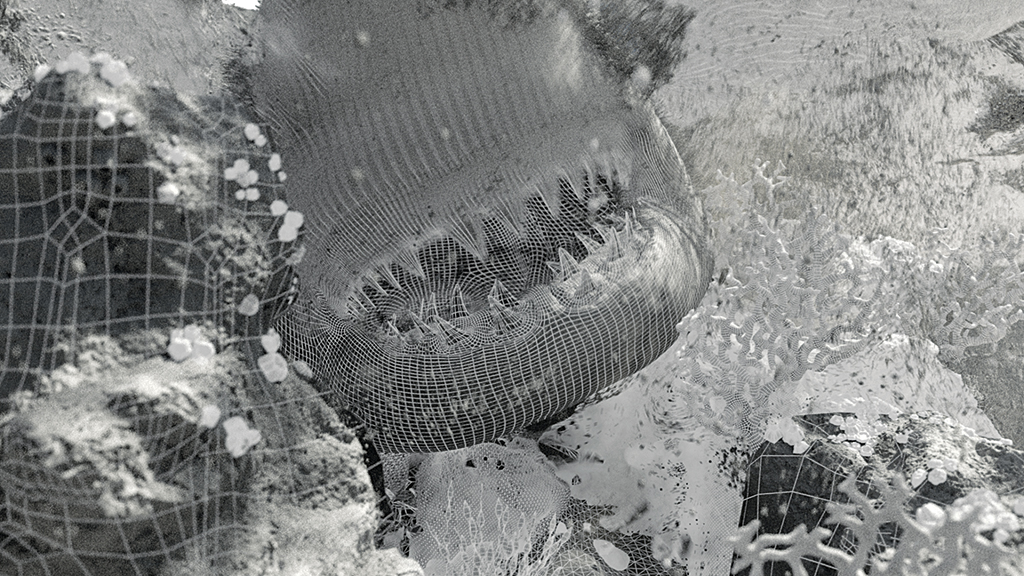

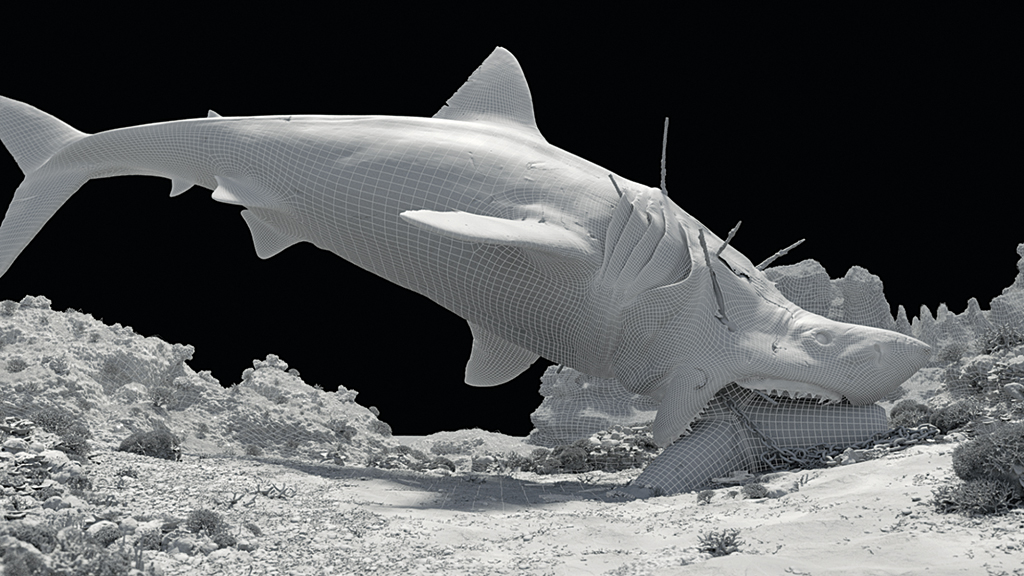

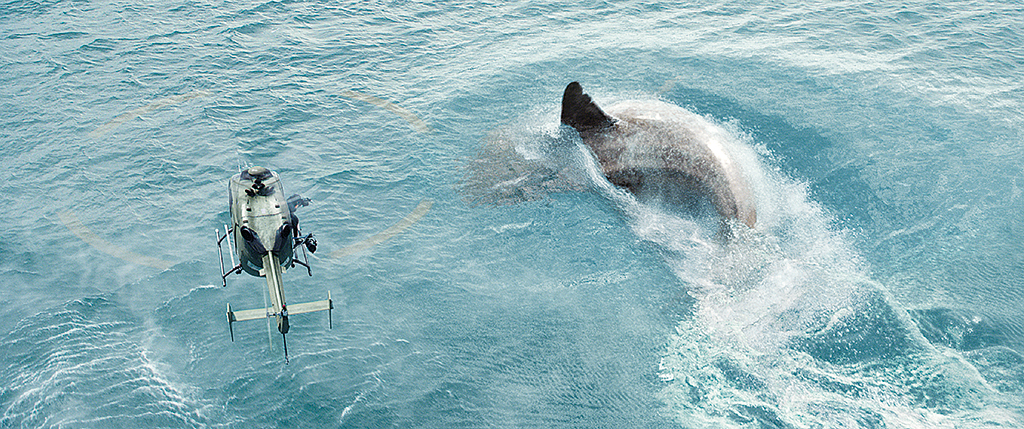

Given its shark is 70 feet long, believability in The Meg is already pushed to the limits. Still, that did not deter Production Visual Effects Supervisor Adrian De Wet from closely referencing real shark behavior and using that as a leaping-off point for the film’s Megalodon.

“The creature is described in the books as looking like a huge albino great white,” says De Wet. “However, that was really not what the director Jon Turteltaub wanted at all. He wanted something that looked prehistoric. And while it makes evolutionary sense for it to have ended up albino and blind after countless millennia in the total darkness of 10km deep, Jon felt that that didn’t work for his vision. Instead he wanted it to look gnarled, textured, aggressive, moody, and dark – most definitely not a great white.”

In addition, De Wet notes that real great white sharks can almost look too ‘smiley’ when they appear head-on, as if with a big grin. So the Meg was designed with a mouth that was less turned up at the sides in order to be scarier. The shape and proportion of the giant shark had to be addressed as well.

“When we modeled the Meg using correct shark proportions, it looked too sleek and thin, with a too-small dorsal fin,” comments De Wet. “So we had to adjust proportions to Jon’s taste, which meant a fatter shark, with smaller eyes and a larger dorsal fin. There were many iterations of the Meg body shape, from long and sleek to shorter and fatter. Too much of a bulbous shape destroys scale and makes it look like a tuna fish or a giant guppy. Too lean and sleek makes it take on the appearance of an eel.”

The Meg’s water sequences were filmed in two tanks built in Kumeu, New Zealand. One was relatively shallow but with a large surface area, and contained a high 200-foot greenscreen on one side for water surface shots. The second smaller tank – a deep water tank – was circular and covered by a ‘blue sky’ roof and lined with blue pool liner.

“This tank was for underwater action shots, such as when Jonas (Jason Statham) battles the Meg underwater in the third act of the film,” says De Wet. “We built a Meg buck for use underwater when Jonas interacts with it. For instance, for the beats where Jonas stabs the Meg in the eye, I wanted a physical, life-sized replica of the Meg’s face, or at least the part that Jason has to hold onto and climb up. So when we locked down the design of the Meg, we went to a fabricator and they made a full-sized half face. However, we soon discovered that it could not be pulled around underwater at any considerable speed because of the massive water resistance and drag forces involved.

“We looked at how the jaws behave when a shark attacks, what the gills are doing when it turns in anger, how fast is the tail moving to propel the massive body, and then we added that extra few percent to exaggerate the action, creating a shark that is not only believable, but also terrifying.”

—Marcin Kolendo, Senior Visual Effects Supervisor, Outpost

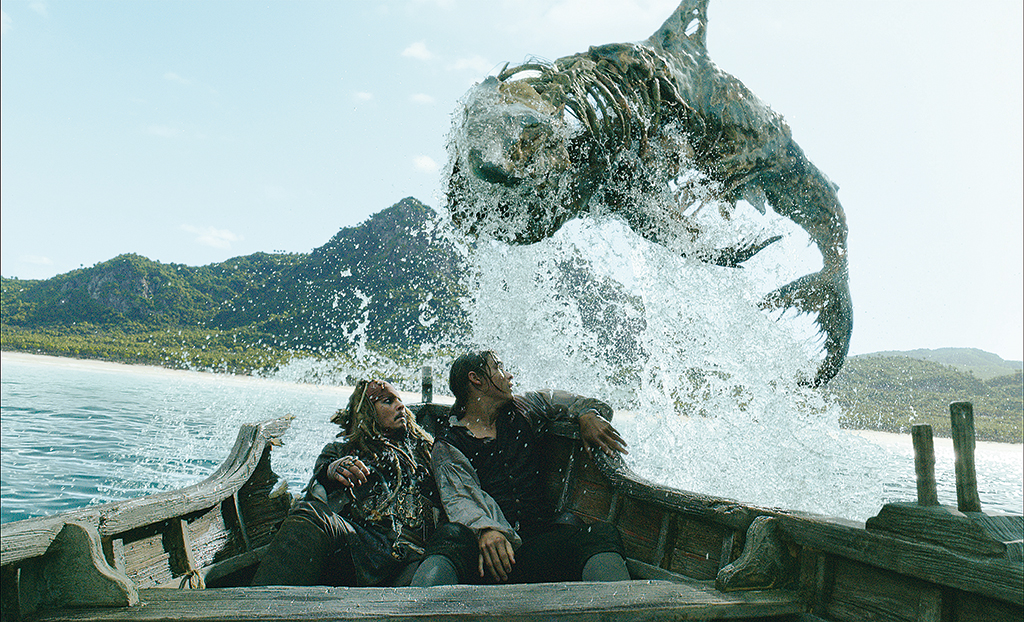

The CG sharks in Joachim Rønning and Espen Sandberg’s Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales were certainly intended to be photoreal, but not so real per se. Instead, these were ‘ghost sharks’ that are commanded by Captain Armando Salazar (Javier Bardem) as part of his undead pirates. Tasked with the shark visual effects work was MPC, led by Visual Effects Supervisor Patrick Ledda.

“We took existing concept work from the production art department and developed them further to achieve the desired look, paying particular attention to what real shark anatomy looks like, but also taking creative freedom when needed,” says Ledda.

“For instance, we gave them a rib cage so we could show some broken ribs even though sharks don’t have this bone structure. We looked at a lot of references of rotten fish and dead animals, which wasn’t the most appealing, but it provided a lot of inspiration for our modelers and texturing artists.”

The sharks were also given broken spines and fins which allowed animators to have the sharks perform erratic, jagged and un-elegant movements. “We wanted them to swim as if they were zombie sharks,” adds Ledda. At one point the sharks take on a rowboat holding Captain Jack Sparrow (Johnny Depp) and Henry Turner (Brenton Thwaites), biting at the craft and jumping out of the water, a task made more difficult by the fact that Depp and Thwaites were shot practically on a stage.

“Creating realistic shark motion, although challenging, is quite objective,” adds Ledda. “There is a lot of reference available for different types of sharks. In our case, it was a much more subjective approach. However, it’s still important to adhere to physical characteristics such as weight, speed and so on in order to make them believable. When interacting with characters, this became quite challenging because they needed to react to certain performance cues while trying to be plausible at the same time.”

Read more about ILP’s shark VFX work here

Read more about ILP’s shark VFX work here