By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Columbia Pictures/Sony.

By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Columbia Pictures/Sony.

Denzel Washington and director Antoine Fuqua enjoy a moment of levity in-between action-packed set pieces. (Photo: Stefano Montesi)

For those wishing to return to the days when effects were predominating done practically, then The Equalizer 3 will be a joy to watch, as the mandate of filmmaker Antoine Fuqua (Training Day) and Cinematographer Robert Richardson (Snow Falling on Cedars) was to capture as much in camera as possible. “The most dramatic thing is the explosion, when one of our leads is impacted by that, and the whole environment she is walking in is essentially digitally created,” states Editor Conrad Buff IV, who assembled the original outing of Denzel Washington as Robert McCall, a former government agent turned vigilante.

The crew at work in Minori, Italy for the driving shot of villain Vincent (Andrea Scarduzio) in the SUV. (Photo: Stefano Montesi)

“Most of it is sweetening existing shots. In some cases, adding backgrounds to moving vehicles and dialogue going on, or cleanup in certain scenes in Italy where we would want to remove some contemporary pieces of equipment on a beautiful old building, like a satellite dish or a communication device. It’s not a strong visual effects film and yet we still have several hundred effects shots.”

Principal photography took place in Italy with Atrani standing in for the fictional Italian town that McCall decides to call home. “Fortunately, the town in the story is not a postcard place that everyone knows about,” notes Production Designer Naomi Shonan. “It’s a place where lives are lived on a small scale, and what we wanted to produce is that feeling of community and intimacy. Atrani has 700 inhabitants and 90% of them are related. You’re trying to make sure that everything in the script is there. That store is such a distance from this. At the same time, you’re being instructed and limited by the real place. I always find that limitations are a source of creativity. Open-ended is not good. If you pretend that you’re infinitely creative, I don’t think you end up with anything that is grounded, and what’s the point?” Some scenes were shot at Cinecittà Studios in Rome. Notes Shonan, “Plates were taken on the location that the sets were supposedly in. The sets were heavily referenced on the real locations because I always find you learn so much from wherever you are. It’s like an anthropology of Italy. You don’t want to pretend that it’s something else. You want to mine it for all it’s worth.”

Stunt Coordinator Liang Yang and his team bring up the stunt person on set. (Photo: Stefano Montesi)

A man (stunt double Gabriele Scilla) in a wheelchair throws himself out the window to protest Marco’s eviction. (Photo: Stefano Montesi)

Denzel Washington reprises his role as Robert McCall for the final installment of The Equalizer trilogy. (Photo: Stefano Montesi)

Clarity in action sequences is essential. “I’m not a fan of things that are so absurdly overcut that are frame, frame, frame,” Buff remarks. “We’re not really watching, but receiving an impression. I’m more old school. I prefer seeing as much as possible what the action is and not trying to mask it with energetic cuts.”. A blueprint was already ingrained into the footage. “There was a stunt and action unit that worked with Antoine and choreographed some of the sequences. They were choreographed tightly, so that when I started to receive them for real, I was obliged to essentially follow the pattern that had been established by Liang Yang [Stunt Coordinator and Action Unit Director]. In this film, a lot of it was predetermined,” Buff says.

Stuntvis was captured onstage based on the script. “There are always challenges when we find out what the location is going to be,” Yang states. “For example, a fast-traveling van hits the villain and crashes onto the church wall. I was really stressed to get the rig I needed and to think of the solution to make the van crash work, because in Rome every single wall and building are historical, so you cannot damage them, and yet I still had to make everything look realistic.”

Only three sequences required stunt wirework. “One was the van crash where we needed a wire to pull the person into the wall,” Yang reveals. “Another one was the car explosion and the stunt double flying backwards. The third is the person being thrown out of the window from the fourth floor. When we do those things, we make sure that the stunt looks realistic but is safe at the same time.” Each project requires different action and fight choreography.

The greenscreen shoot for the car explosion that takes place outside a police station in Naples. (Photo: Stefano Montesi)

“We’re Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones, not Mick Jagger. When you’re doing a creature-driven movie, then you’re front and center; however, here we’re supporting the practical photography. The biggest challenge was trying to dust off that part of your brain that developed when CG wasn’t an option and you had to rely on practical. It has come together quite well.”

—James McQuaide, VFX Producer/ VFX Supervisor

“My trick is to analyze the script inside out, find the key element for that particular action sequence and understand the character’s motivation. Antoine wanted McCall’s fight movements to be very brutal, fast and intended to kill. This is because the villains in this story are truly evil, and McCall wants them to receive the punishment they deserve,” Yang says.

VFX Producer/VFX Supervisor James McQuaide shoots background plates with the ACHTEL camera for the Naples car explosion scene.

The stunt team carefully choreographed the fight sequences by shooting stuntvis to inform the final cinematic result. (Photo: Stefano Montesi)

The van crash was tricky to accomplish, as the necessary equipment had to be improvised and the walls of the church were considered to be historical, so they could not be damaged. (Photo: Stefano Montesi)

Amongst the invisible visual effects work is the addition of CG vehicles to the plate photography.

Between 550 and 600 visual effects shots were created by Blackbird VFX, Frame by Frame, Future Associate, Luma Pictures, ModelFarm, slatevfx, Supervixen Studios and an in-house team. “The significance that visual effects are playing in this movie is probably more than I anticipated, but that makes for more fun,” remarks James McQuaide, VFX Producer and VFX Supervisor.

“James [VFX Producer/VFX Supervisor McQuaide] has a great team of postvis artists who are able to create close to final-quality visual effects for us and have been instrumental in shaping and designing, not just one particular shot but certain sequences. It has definitely been great to have that tool at our disposal to help shape and fix things as Conrad [Editor Conrad Buff] thinks of something. These postvis artists are able to do it relatively quickly and get it back to him so he can review and cut it in.”

—Steven Cuellar, Visual Effects Editor

“An interesting challenge was that [Cinematographer] Robert Richardson has custom lenses, which have focal lengths that aren’t necessarily accurate. Several times we were trying to shoot these elements and construct things practically where the focal length between his lenses and the other lenses didn’t match; that required a certain figure-it-out-as-you-go process, which I hadn’t run into previously.”

Details were incorporated into the imagery, McQuaide adds. “A small example is when we added clothes lines in the small Amalfi town to take what Naomi had done and make it prettier,” he says. Theatrical muzzle flashes and blood hits were not an option. “They had to underscore what was going on, but Antoine was most interested in accuracy. All of the muzzle flashes that you see in the pictures were shot with those guns. There is little blood in the movie that is practical,” McQuaide notes.

Evercast was utilized to discuss visual effects shots with Buff and Fuqua, while vendor notes were sent via PIX. “PIX is handy because vendors can clearly see what James is talking about and throughout Italy. I would do my own test comp inside the Avid and present it to Conrad; he would give me directions, so I would refine it and give it back to him. When it gets to something like bullet hits or blood splatters, that goes above me, and we send those over to postvis!” Postvis was a critical part of the editorial and visual effects process, Cuellar says. “James has a great team of postvis artists who are able to create close to final-quality visual effects for us and has been instrumental in shaping and designing, not just one particular shot but certain sequences. It has definitely been great to have that tool at our disposal to help shape and fix things as Conrad thinks of something. These postvis artists are able to do it relatively quickly and get it back to him so he can review and cut it in.”

The high-quality postvis was used for studio screenings and extremely cost-effective, McQuaide explains. “It allows you to wait until the cut begins to solidify, and therefore not throw away a lot of shots. We’re using Company3’s Portal. Everything is online and sent to the vendor within 24 hours or less. It turns over in three or four days.”

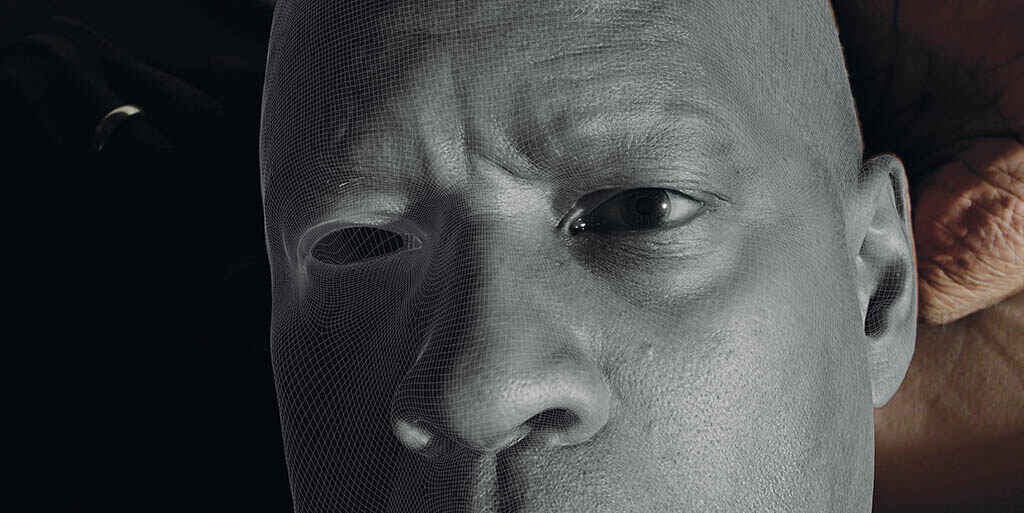

Stable Diffusion was integrated into the Maya and Houdini pipeline belonging to Luma Pictures to achieve the desired face replacements. “We are using the Stable Diffusion method to rapidly prototype how a face could look in a plate lighting context,” remarks Brendan Seals, VFX Supervisor at Luma Pictures. “We are still sculpting expressions and certain blend shapes for the base mesh that is being fed into Stable Diffusion via a normal map. We are boxing the AI into certain boundaries that conform to the proportions of Denzel Washington’s face. That’s important because it’s all too easy now to generate Denzel circa 10 to 15 years ago, provided to us of Denzel in the scanning booth and AI to up-res the photography of him lying down.”

A key visual effects moment is when a car bomb goes off in a piazza outside of a police station. “That was the big job that we had to do because everything was shot in many different locations in Rome and Naples,” remarks Fabio Cerrito, Head of VFX at Frame by Frame. “We built a rough environment based on the LiDAR scans that had been given in order to use it to cast the shadows on top of everything. We had some debris coming from the real explosion, but they didn’t give us the proper brutal force that type of explosion would have. We had to recreate and choreograph them in CG. There are a lot of cars that react to the explosion by shaking and the tempered glass cracks into a typical spider web. We had to add tons of different smoke details. The main plate was shot in normal daily life where people are walking the dog or buying a newspaper. The thing that we had to be careful of was having people in the background reacting to the explosion. It is another small touch, but makes the effect look believable.”

190-degree 9.3K plate photography of the piazza in Naples was captured using the ACHTEL 9×7 Digital Cinema Camera and Entaniya HAL 220 LF fisheye lens. “One of the things that the camera can do is, I can login to the camera from anywhere in the world and completely take over,” remarks Pawel Achtel, Director and Producer with ACHTEL Pty Limited. “James was telling me when to roll and cut the camera. I was ensuring that the camera exposure and settings were correct. Then, at the end of the day, I was able to back up the footage and transcode it to what they needed remotely from Sydney. James joked that DPs work from home these days!” A major concern had to be addressed, Achtel adds. “There was a massive difference between the shadowy areas and this white billboard that the sun was hitting. James wasn’t sure whether that stuff would be clipped. I intentionally shot it with slightly clipped highlights so we could get better exposure in the shadows, and reconstructed the highlights 100% with all of the detail and color matching, which was quite extraordinary.”

Five weeks before locking the picture, ideas were still being tried out. “The bad guys are involved with some bombs going off in Rome, but we only see the aftermath,” McQuaide states. “We made a temp shot from stock footage of a train station in Rome for Antoine to take a look at, where we actually see the explosion from a surveillance camera. By putting that in the movie you are increasing the stakes. You now really hate the villain because you’re seeing innocent people being killed by these bomb explosions. Sometimes, it’s putting people physically in danger, but in this case it’s something more abstract than that but still important. You’re actually seeing why the bad guy gets the punishment he gets in the end.” A music analogy accurately describes the visual effects work in The Equalizer 3. “We’re Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones, not Mick Jagger,” McQuaide observes. “When you’re doing a creature-driven movie, then you’re front and center; however, here we’re supporting the practical photography. The biggest challenge was trying to dust off that part of your brain that developed when CG wasn’t an option and you had to rely on practical. It has come together quite well.”

Rising Sun Pictures utilized AI to get the necessary detail for the eye of Denzel Washington in the McCall Vision scene.