By IAN FAILES

By IAN FAILES

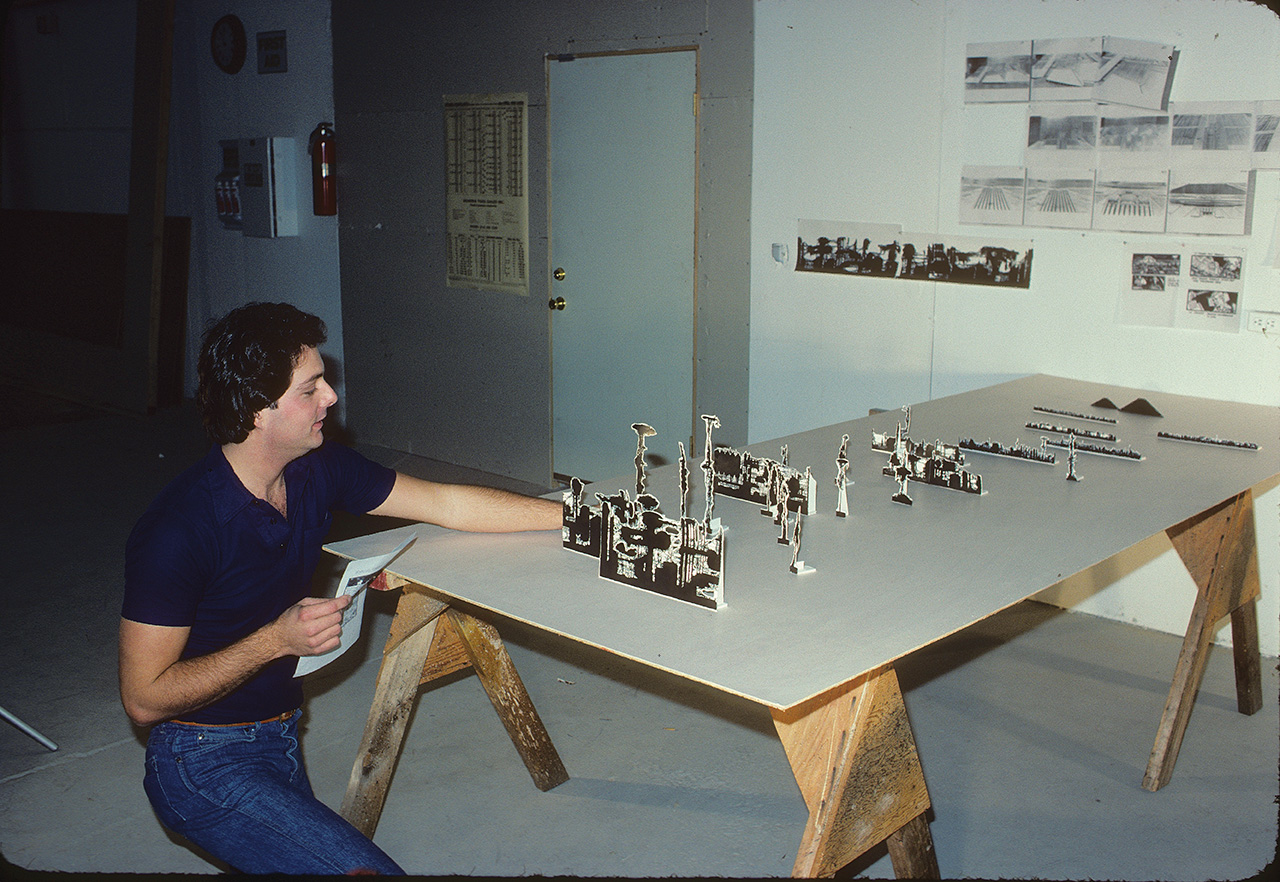

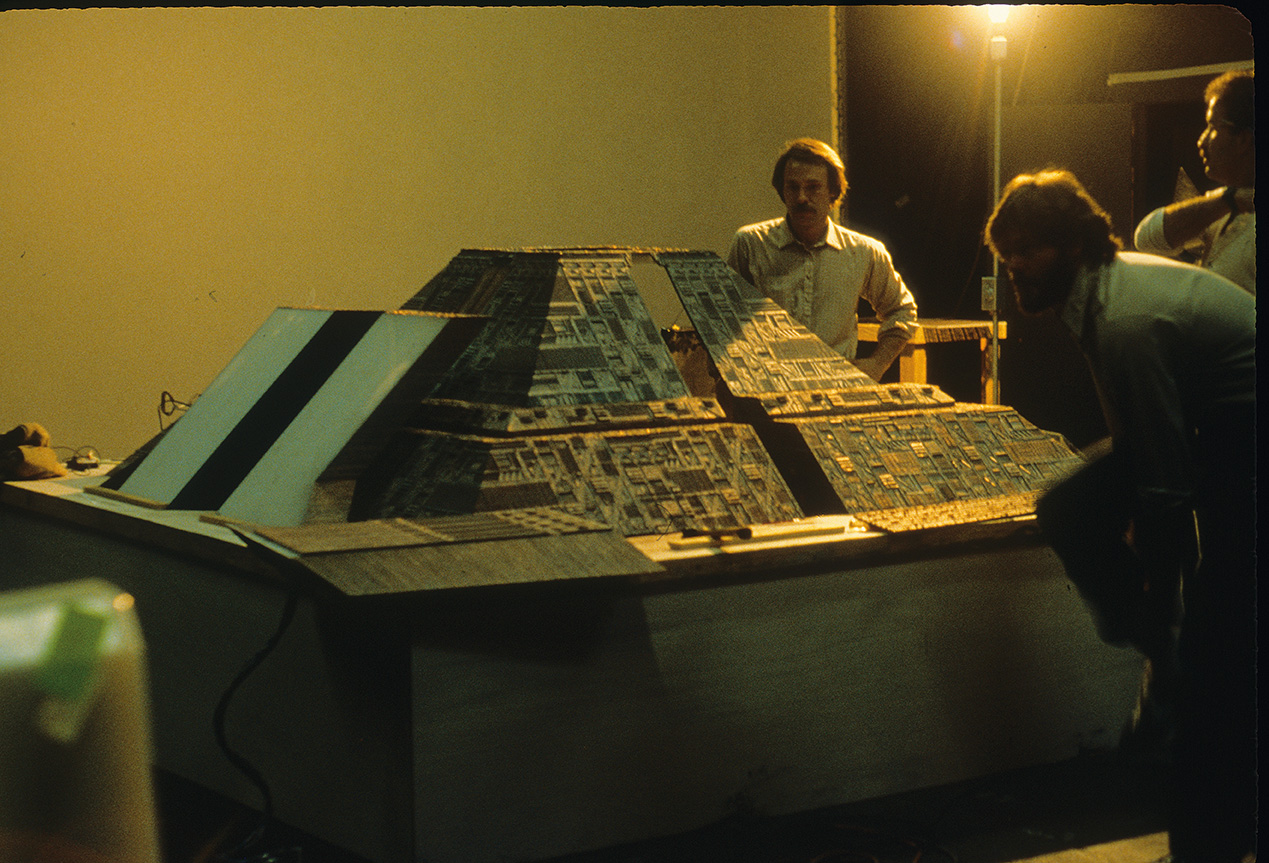

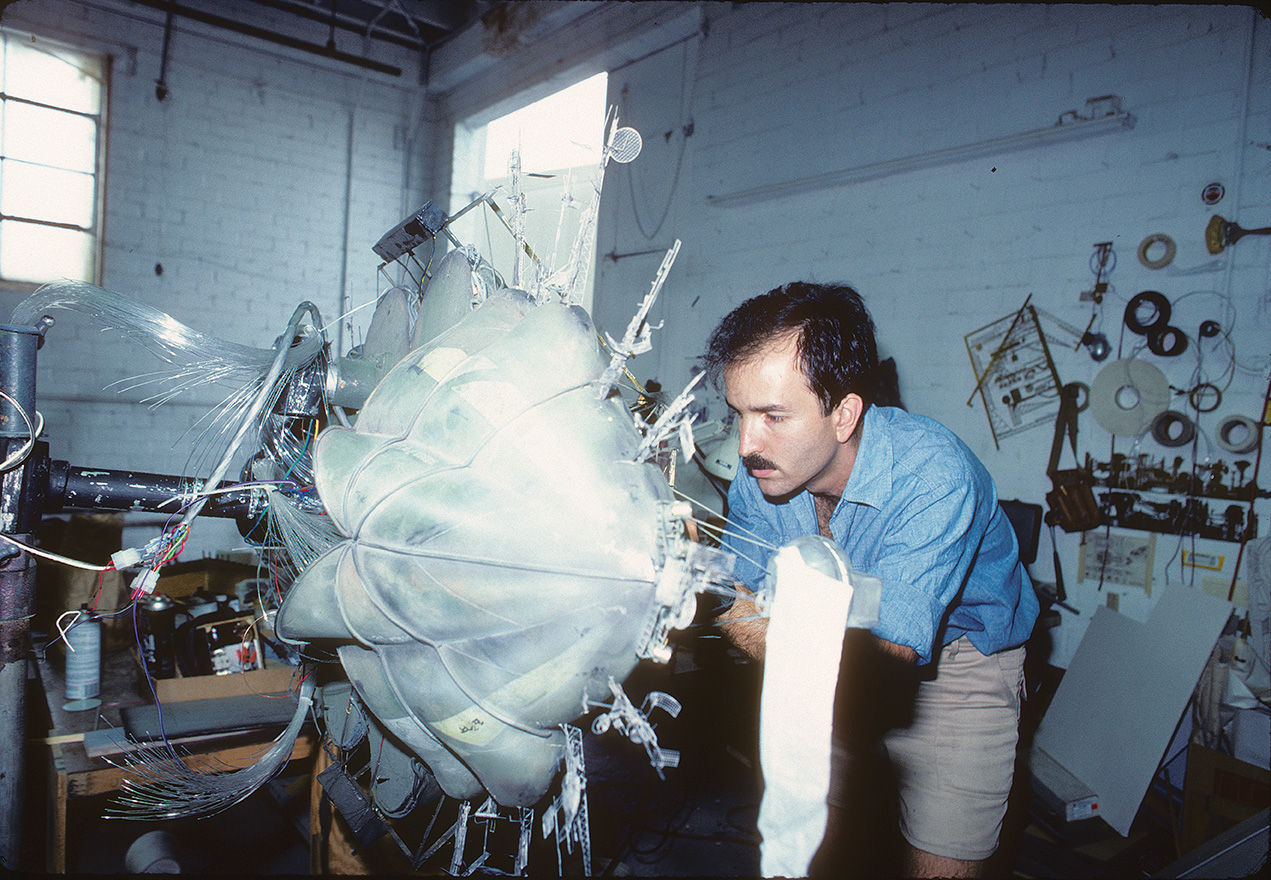

Christopher S. Ross checks the scale convergence of the Hades Landscape. The artist drew the black silhouettes, in progressively reduced scales, over Virgil Mirano’s reference photography of the El Segundo refinery. They were arranged on 12” x 24” artboard panels from which lithographic films were made. The acid-etching supplier used the films to print stencil masks onto 12” x 24” brass sheet stock for etching the silhouettes (similar to the process used to make printed circuit boards).

Christopher S. Ross checks the scale convergence of the Hades Landscape. The artist drew the black silhouettes, in progressively reduced scales, over Virgil Mirano’s reference photography of the El Segundo refinery. They were arranged on 12” x 24” artboard panels from which lithographic films were made. The acid-etching supplier used the films to print stencil masks onto 12” x 24” brass sheet stock for etching the silhouettes (similar to the process used to make printed circuit boards).In 1982, Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner set a distinctive tone for the look and feel of many sci-fi future film noirs to come, taking advantage of stylized production design, art direction and visual effects work.

Supervisors Douglas Trumbull, VES, Richard Yuricich and David Dryer – via Entertainment Effects Group – oversaw Blade Runner’s Oscar®-nominated visual effects; work that was completed at a time when practical effects, miniatures, optical compositing and real film (in this case, 65mm film) were the norm.

On the eve of the release of Denis Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049 sequel, VFX Voice revisits the miniatures of the original film with chief model maker Mark Stetson, VES. He and a crew of distinguished artists helped to craft many of the film’s iconic settings and vehicles, including the opening Hades landscape,

Tyrell Corporation pyramids, the Spinner and other flying vehicles, the advertising blimp and the Los Angeles city landscape of 2019.

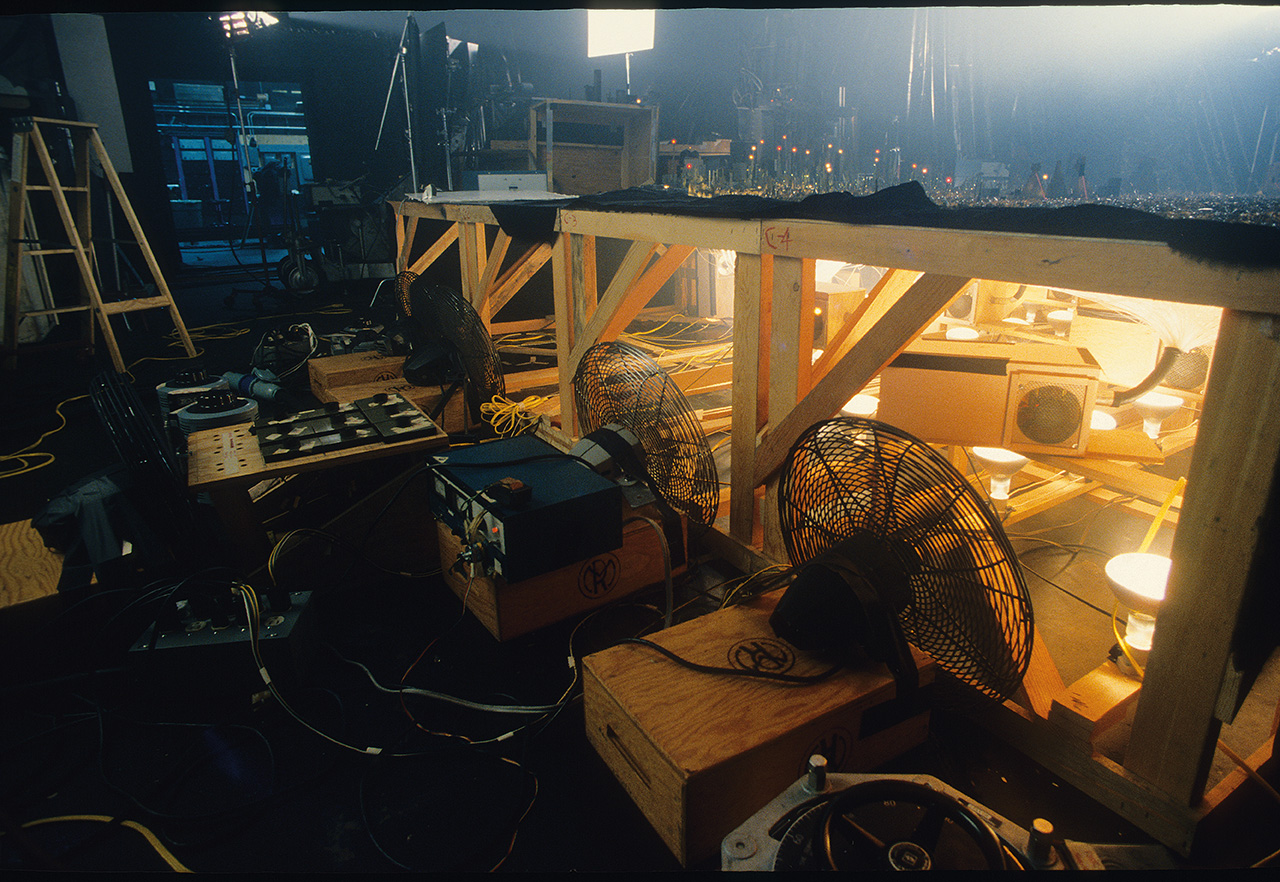

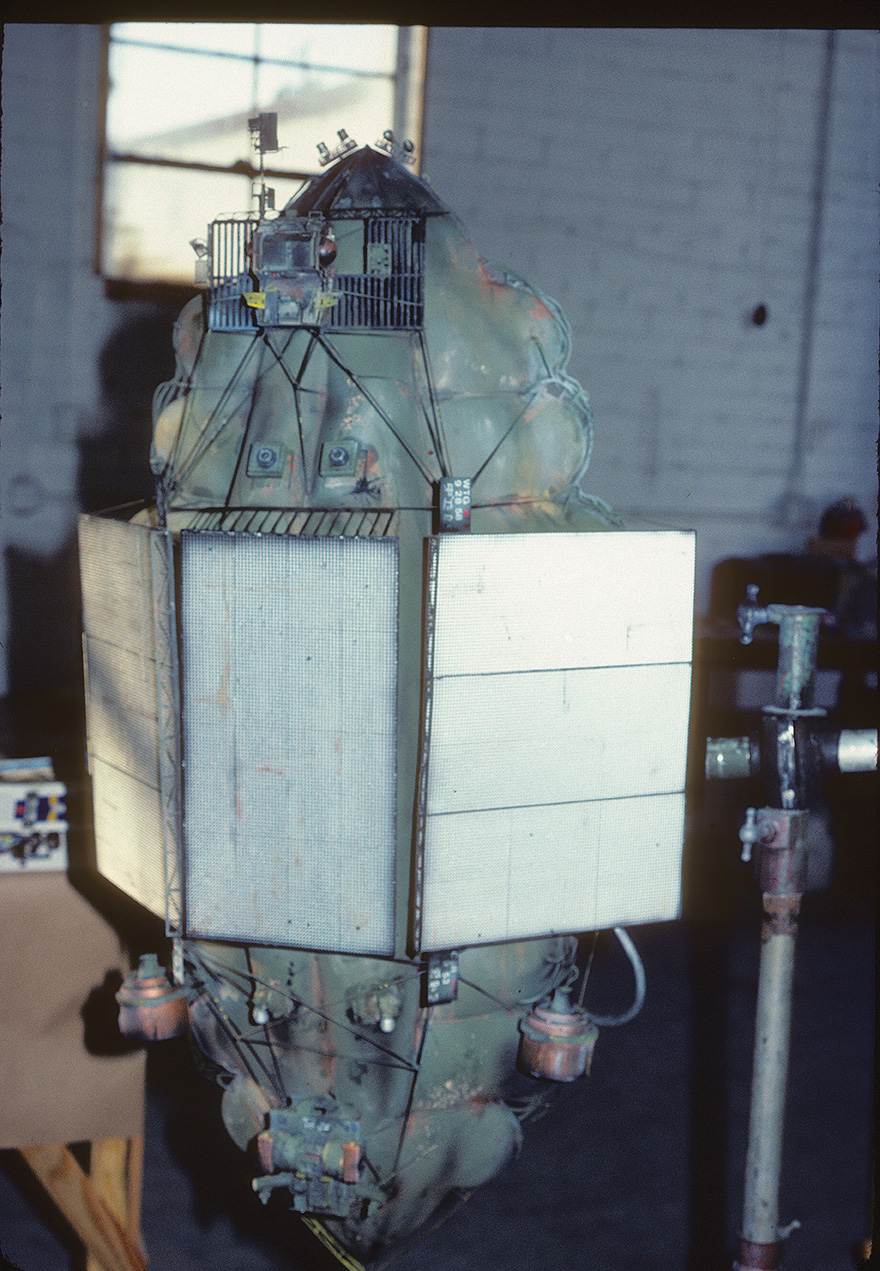

The Hades Landscape model on the smoke stage set up on tables with under-lighting. Fans helped control the heat generated.

The Hades Landscape model on the smoke stage set up on tables with under-lighting. Fans helped control the heat generated.AN INDUSTRIAL BEGINNING

Blade Runner begins with a slow push-in over a heavily industrialized section of Los Angeles. Many were surprised when it became apparent that the endless refinery imagery – known as the Hades landscape – was largely achieved with rows of acid-etched brass silhouette cut-outs in a forced perspective layout.

“The original thought,” says Stetson, “was that Hades would be shot in a smoke room, it would all be backlit, and we would build it on a transparent tabletop so we could angle the lights with these rows of silhouettes. It didn’t really work out that well in that respect – there wasn’t enough lighting control or depth in the fine-scale miniature to separate the layers. So we decided to add a ground plane of cast-detailed parts to the foreground.”

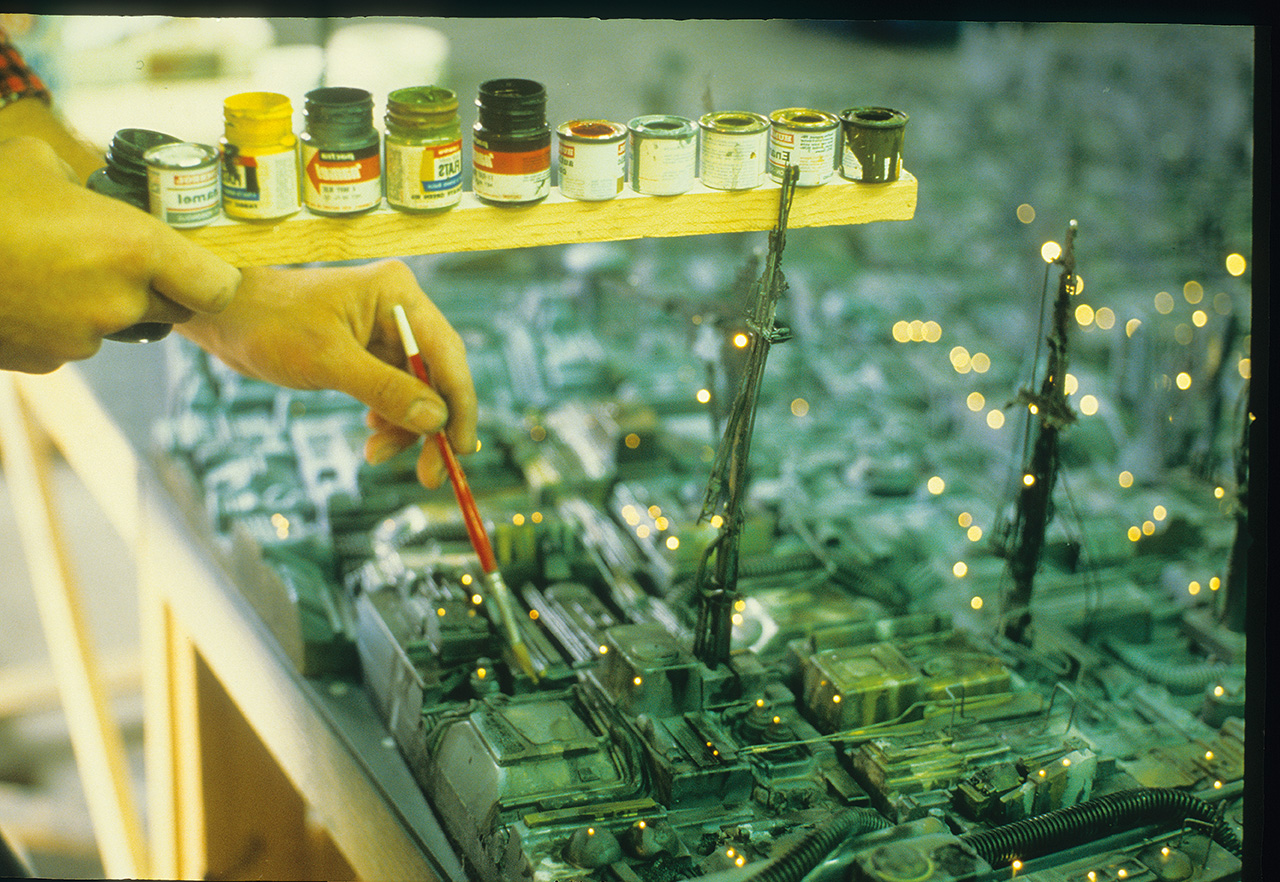

The ground plane structures were painted quite roughly to make the buildings look ‘aged and crappy’ – instant coffee was even used for that effect. Then, after making an evening flight into Los Angeles, Stetson was inspired to replicate in the Hades landscape the look of thousands of city lights.

A myriad of fiber optic strands – seven miles worth – was added underneath the tables holding the silhouettes and other model pieces. The lights included a mix of different bulbs, too, all filmed in different passes, as were the gas flares captured ‘in-model’ with specially placed projection screens and a synchronized 35mm film projector.

PYRAMIDS OF THE FUTURE

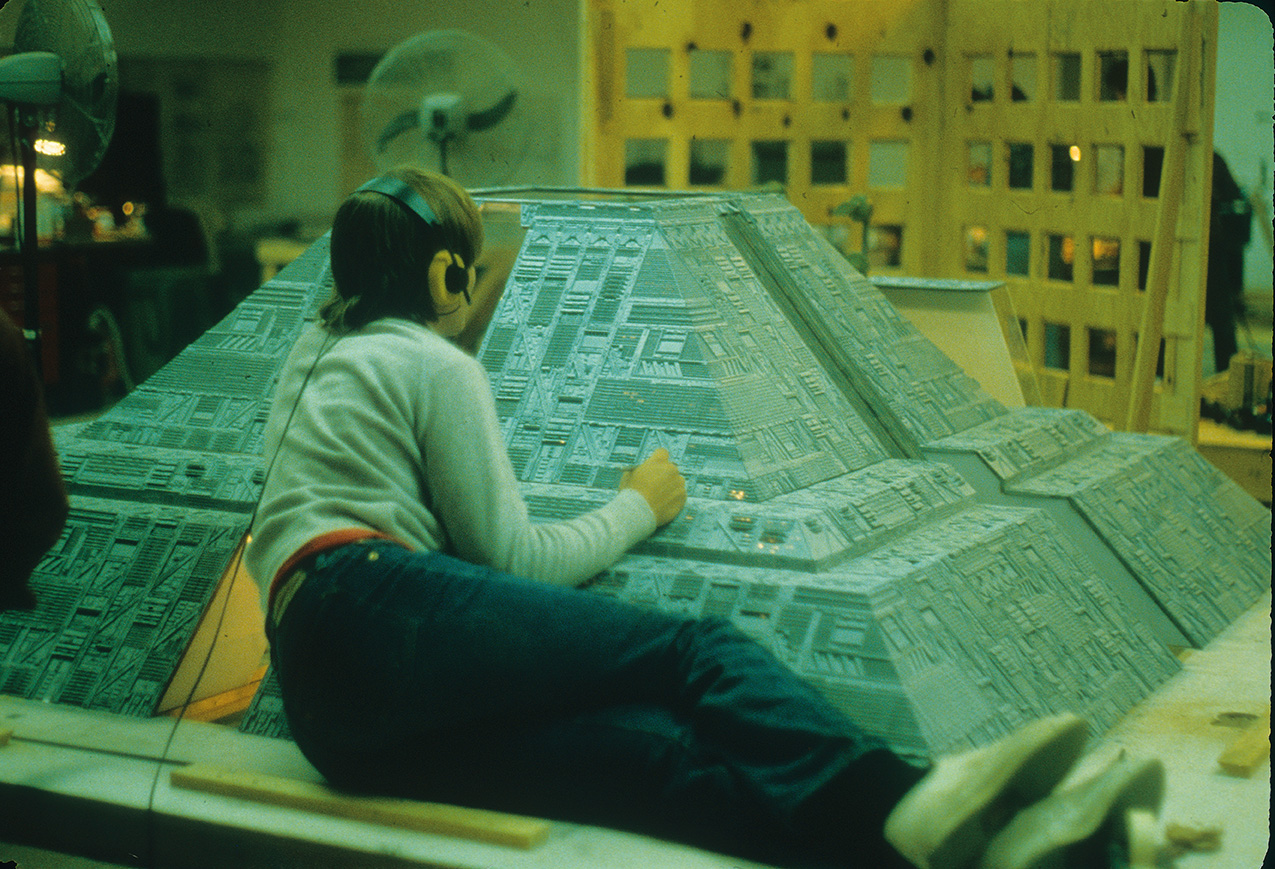

The Tyrell Corporation, responsible for genetically engineered replicants in the future-verse of Blade Runner, has its headquar- ters in a pair of enormous pyramid-shaped buildings constructed by Stetson’s team as miniatures. Their trademark look involved intricate side panels made to look as if consisting of thousands of lit windows.

The core pyramid structure was built essentially as a clear plastic shell. Flat panel patterns were accurately cut to make up the basic pyramid shape. The patterns’ surfaces were intricately detailed with plastic strip stock. “We laid down one quarter-inch plastic angle stock on its edges to create a stair-step surface,” says Stetson.

“On what would become the vertical faces of the steps we added tiny plastic strips of raised detail to indicate window casements, which eased the process of scraping off the window openings later.”

Rubber molds were poured over the completed patterns. Then a new set of pyramid panels were cut from clear Plexiglas, exactly matching the pattern panels. The inner surface of the molds was spray painted with automotive primer and then opaquing fluid, then poured full of clear polyester casting resin and ‘squish- molded’ with the pre-cut Plexiglas sheets pressed into the mold. When assembled, this made up the clear plastic shell for the pyramid structure.

Once put together, the paint covering the raised plastic window areas was then hand-scraped away to make it appear like windows and lights all across the pyramid. “The whole thing was ultimately just lit from within by a 10K bare bulb on the smoke stage,” says Stetson.

“This required a ton of fans just to keep cool.”

Concurrently, the model shop was producing double layers of acid-etched brass sheets to face the flying buttresses on each side of the pyramid. The buttress design posed a different lighting problem, which Kris Gregg solved with U-shaped fluorescent bulbs. “Despite heavy filter correction,” notes Stetson, “the buttress lighting was notably cooler in color than the main pyramid. We decided that was just part of the look of the building.”

SPINNING OUT SPINNERS

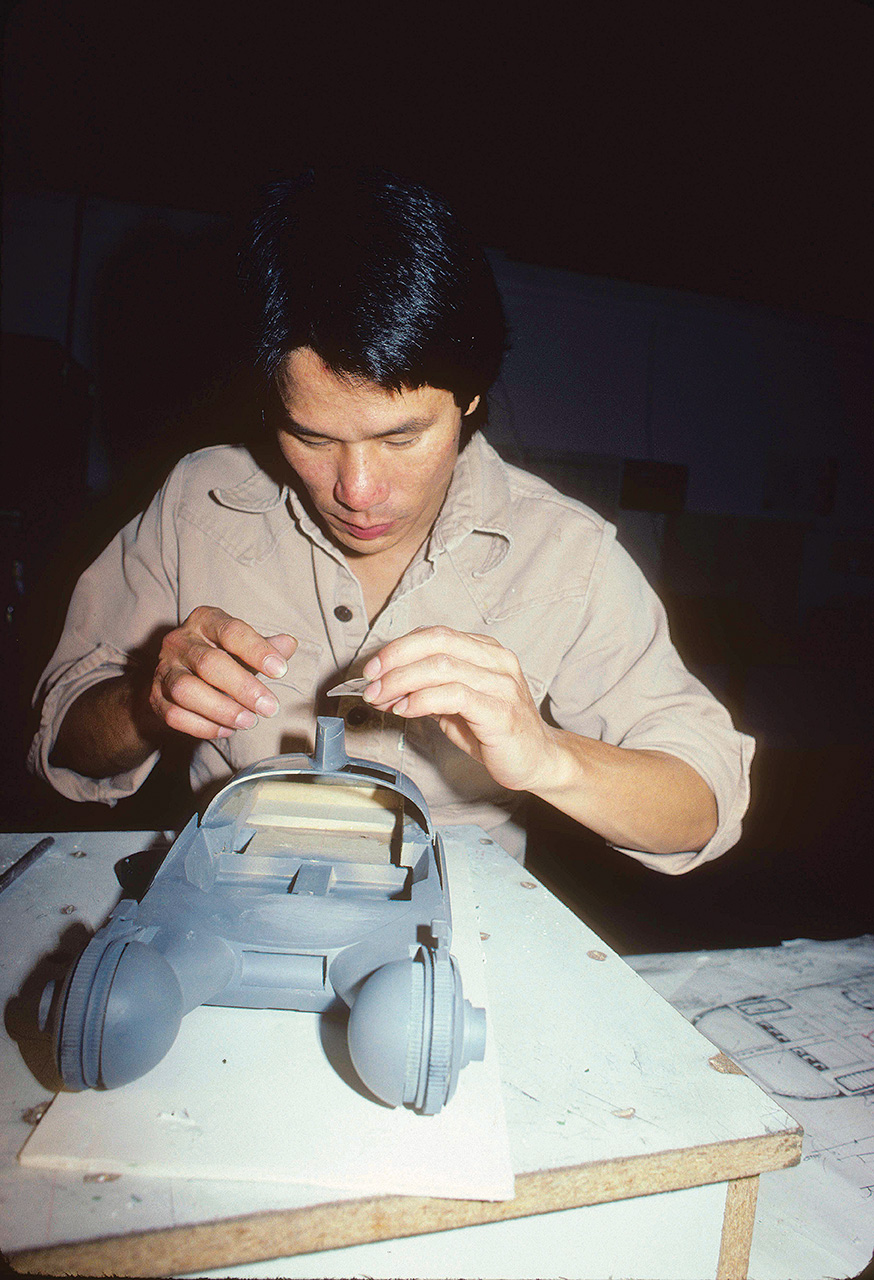

Equally iconic in Blade Runner lore are the flying police vehicles known as Spinners. In visual futurist Syd Mead’s design explora- tions for Blade Runner, he called the flying vehicles ‘aerodynes’

– Spinner was a brand name. Modelmakers crafted several scales of Spinner models (there were also full-sized versions built by legendary hot-rodder Gene Winfield) ranging from one inch to 50 inches.

The models were laid up in molds made from original wooden patterns, with plastic detailing and a vacuum-formed canopy.

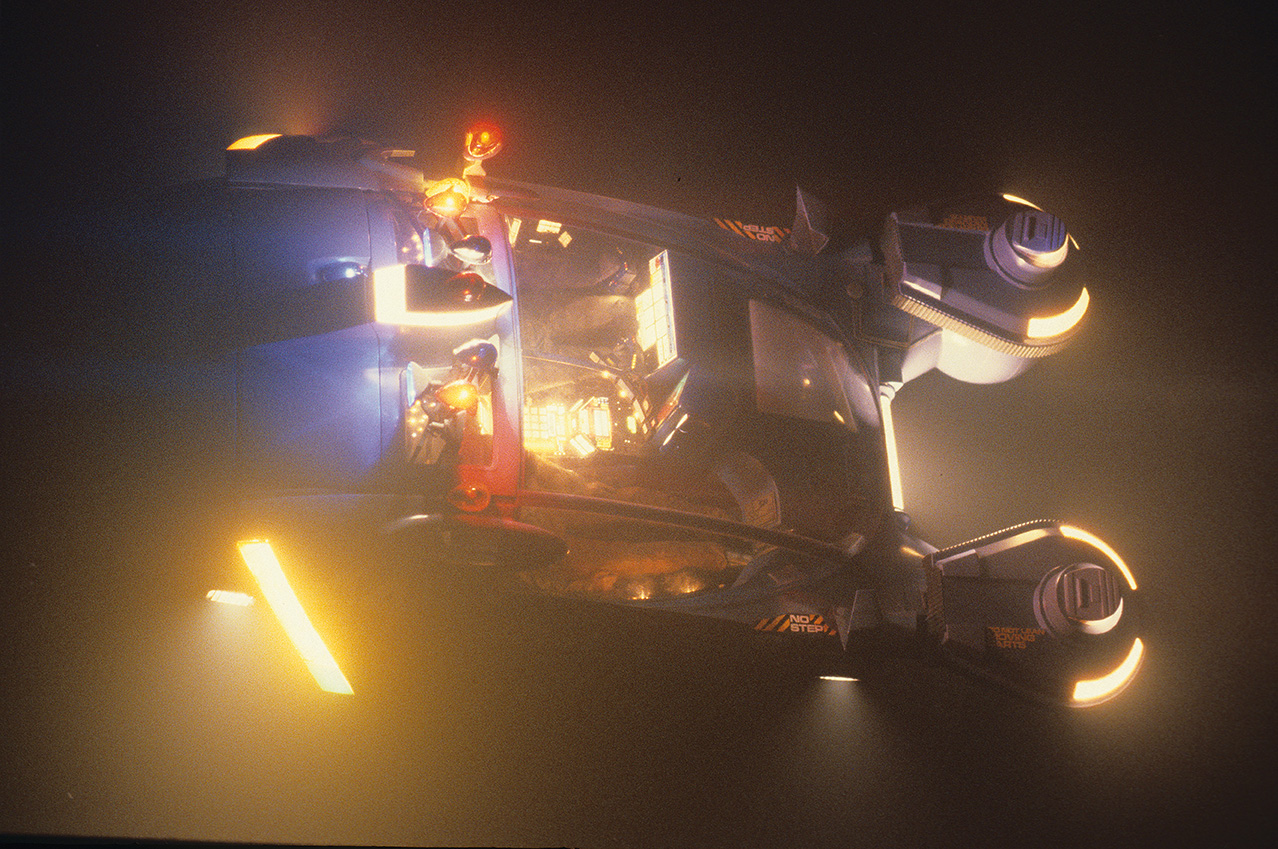

The vehicles were particularly recognizable for their flaring and spinning police lights. In fact, the larger scale Spinner models were a significant feat of engineering. They were made to include room for cabling, stepper motors, lighting, and even nitrogen plumbing for exhaust.

“Late in the development of the models, Ridley asked for a rack of gumball-style police lights to be mounted on top of the car,” says Stetson. “Getting the lights to spin on the model required a new lighting rig that replaced the rear bodywork on the model and was shot on a repeat pass using motion control. We made little brass cans for each halogen light, with lensed snoots driven through speedo cables by a rack of stepper motors on the back of the car.

Shooting in a heavily smoked stage, you’d see these beams of light rotating around, done on a second pass on the model. It was really effective and it really looked beautiful.”

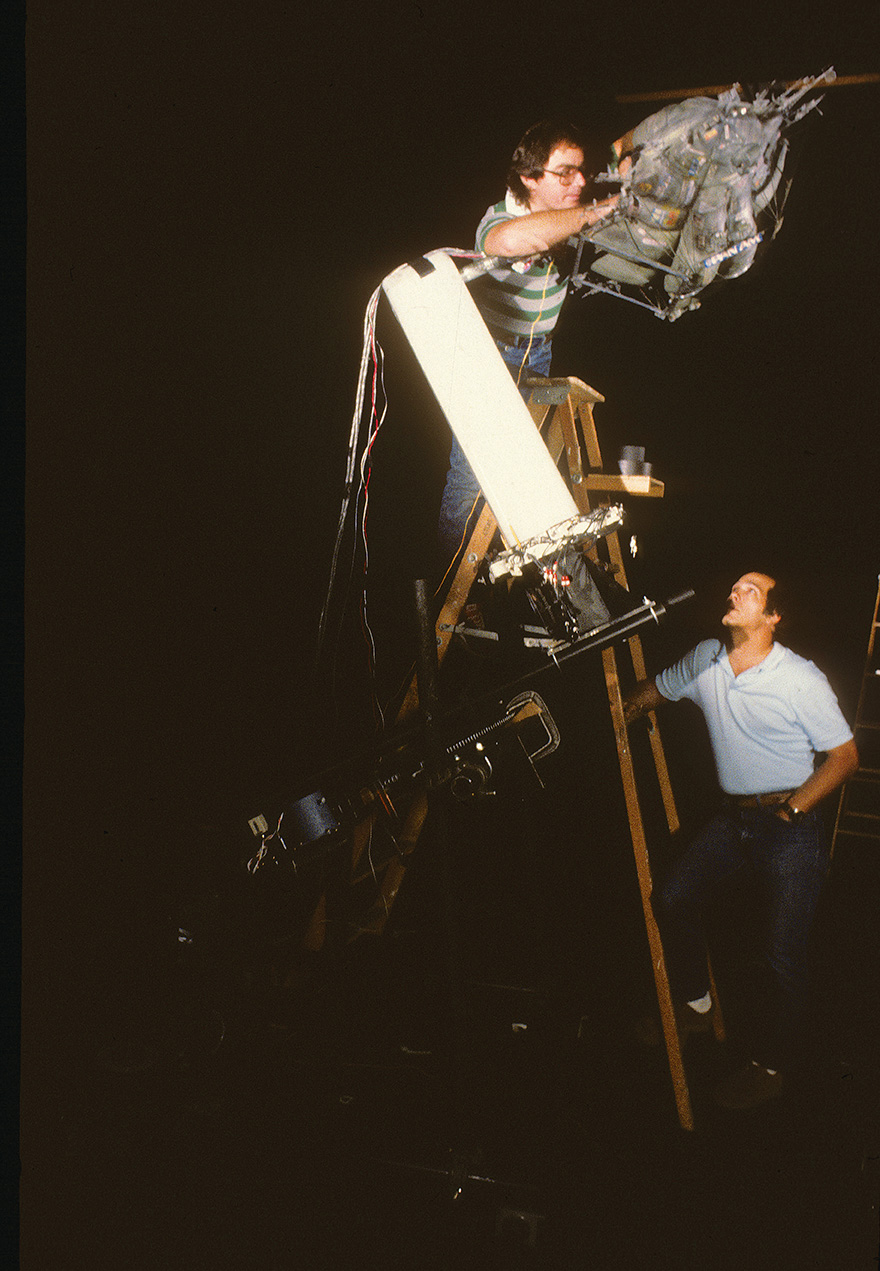

BLADE RUNNER’S BROADCASTING BLIMP

A feature of future Los Angeles is a blimp that hovers over the city with video-screen advertising on its sides. It was realized as a miniature craft, wired with a mass of fiber optic cables for lighting,

and had footage thrown onto the screens via a synchronized 35mm projector during a second pass.

Stetson imagined making the blimp by cutting a template of the perimeter into a thick piece of plywood, then stretching a piece of surgical rubber sheet across it. “I thought we could just fill it with plaster and let the weight of it sag the rubber sheet and we’d get a real nice pneumatic feel to our mold,” he says. Although the plaster proved too heavy for that concept, the modelmakers were able to generate an ‘organic’-looking shape around which they retrofitted framework and many intricate model parts.

The blimp had three projection screens, which were actually re-purposed trays from a children’s magnetic ball game (these were also used for a particularly iconic shot of a Geisha appearing on the side of an LA skyscraper). “We painted the trays opaque black and then dry-brushed silver paint over the top of them,” outlines Stetson. “That became our somewhat pixelated-looking projection screen.”

CITY BUILDING

Miniature city buildings and environments, along with matte paintings, made up views of a 2019 Los Angeles. The model buildings were a purposely mixed bag of structures and recycled constructs, as well as some secret inserts included by Stetson’s team. Look out for a building that has a suspiciously similar shape to the Millennium Falcon, based on Bill George’s 5-foot replica. Also look for Jon Roennau’s 4-foot replica of the Dark Star ship from the John Carpenter film. “Basically,” says Stetson, “it was like, turn everything you could possibly find into a building and throw it in the city.”

An initial set of miniature buildings was constructed in a traditional manner with the buildings sitting on the floor, which fulfilled storyboards that were conceptually more like vertical set extensions of the city street set at the Burbank Studios. Ridley Scott soon desired shots to be achieved as aerials with a complicated mix of city structures below.

“What Ridley really wanted was more of Syd Mead’s visualization of the future for the film, with soaring megastructures planted among the decaying remains of the old city below,” recalls Stetson. “So the emphasis in the miniature build shifted to huge towers and high-altitude aerial views.” Since the motion-control camera rig was such a large apparatus, obtaining high-angle shots presented a rigging problem. The solution: tilting the buildings and allowing for a lower angle of attack.

“These pieces of motion-control equipment were big and heavy because they were designed to carry 65mm cameras,” notes Stetson. “We just didn’t have the height in the studio and we couldn’t get the camera high enough to make these moving shots work unless we tilted the models over.”

Read about the groundbreaking visual effects of Blade Runner 2049 here

Read about the groundbreaking visual effects of Blade Runner 2049 here