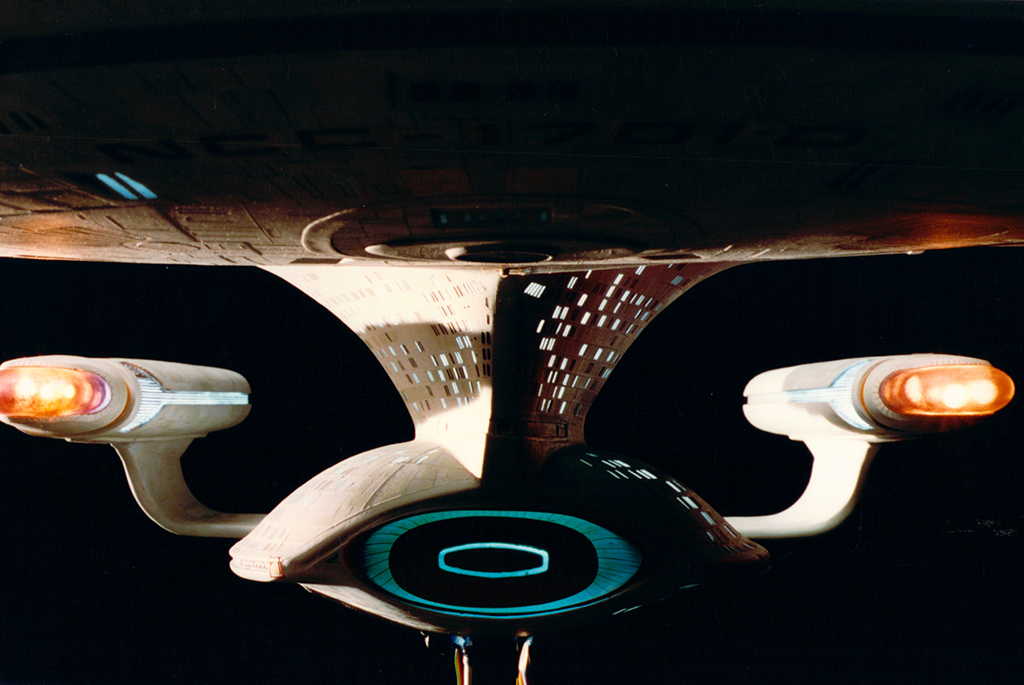

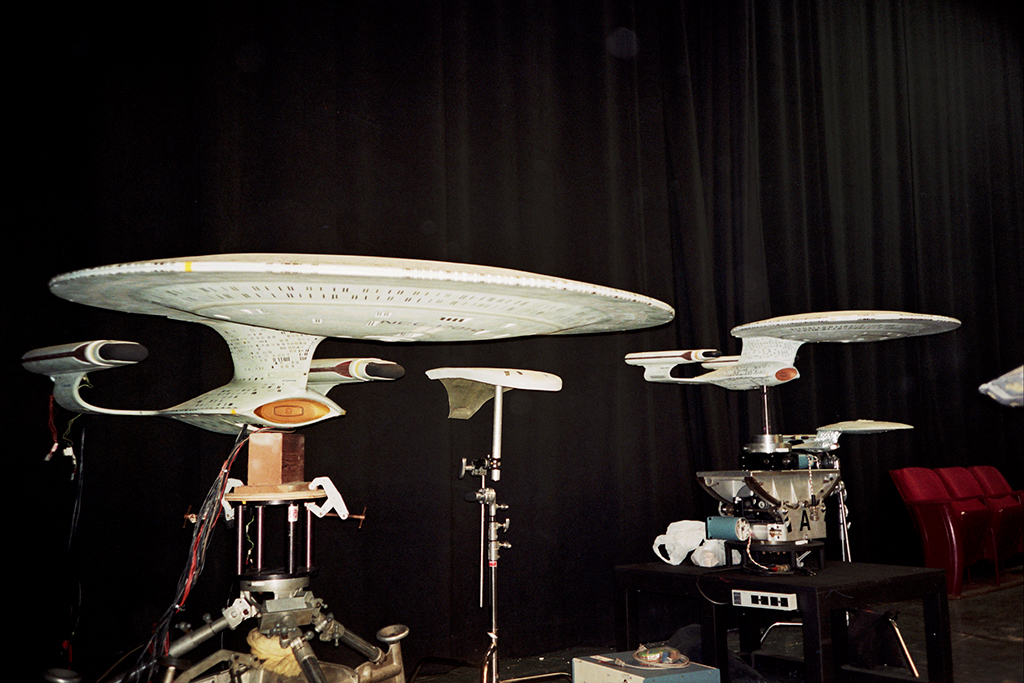

The classic Trek ships seen in The Next Generation were physical miniatures filmed on Image G’s motion-control stage in Hollywood. Traditional oil matte paintings were also a mainstay of visual effects production, relying primarily on the work of Emmy Award-winners Syd Dutton and Bill Taylor, VES, ASC of Illusion Arts. The result was significantly high quality work, which was actually something Curry suggests came from audience expectations after seeing the oft-lauded feature work supervised by artists like Douglas Trumbull VES, Dennis Muren VES, ASC and Richard Edlund VES, ASC.

“We realized we had an obligation to the audience because by that time they had seen Star Wars and other visual effects films that had huge budgets. Of course, we didn’t have huge budgets, nor did we have time. But we were pretty much expected to turn out half a feature for every episode and VFX team members were no strangers to 60 to 80 hour weeks.”

A typical ship fly-by back then might have taken an entire day to film with motion control. If multiple ships were involved, that time could easily extend to a whole week, especially if explosions and special interactive lighting were required. Part of the issue was that the elaborate bluescreen motion-control systems were only the domain of VFX behemoths such as Industrial Light & Magic.

The Trek team had therefore been shooting ships against white cards for matte passes. To contain the silhouette of the model, each foam core card was necessarily set at a different angle to the source of light. That unfortunately resulted in a slightly different luminance on each card and therefore different densities on each matte element as the cards were repositioned to accommodate the camera moves.

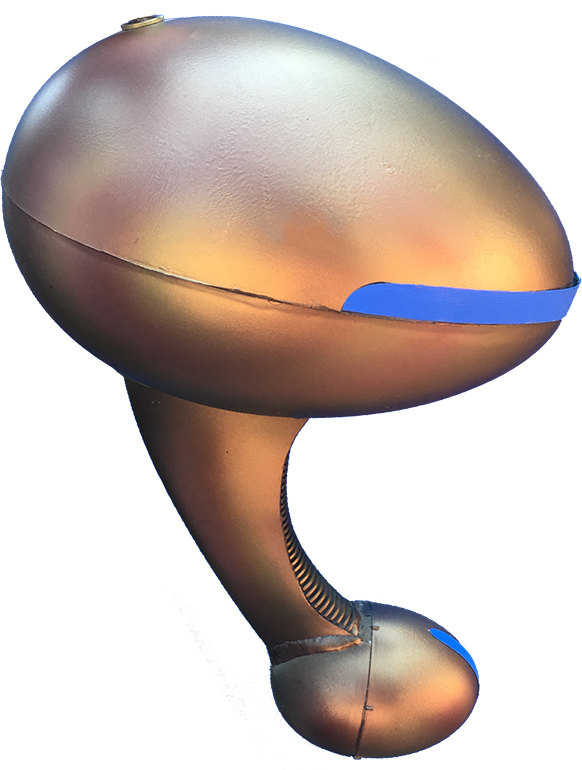

This all changed when Gary Hutzel came up with the idea of using dayglow orange screens and cards illuminated by ultraviolet light. Now whatever angle the cards were placed resulted in the same luminosity. “Suddenly it didn’t matter what angle the cloth or card was to the camera as the luminosity was even all along,” recalls Curry. “That was a real Godsend for all of us.”